|

Monday, April 13, 2009

Progress Notes

Over the years I have noticed while driving the roads of our county how farm fencing has changed. When I was a boy one could still see rail fences being used (photo 01), which I suppose were the first kind of barrier used to keep livestock contained from free ranging.

01 Split Rail Fence When barbed wire and later woven wire were available they were attached to hand cut oak posts (photos 02 and 03).

02 Hand Cut Post Woven Wire Fence

03 Wood Corner Post I can remember how much work was involved for the farmer to cut, shape and then drive with a sledge hammer those posts into Ozark hill rocky ground, sometimes requiring a crow bar to get through the rocks. Later on handheld post hole diggers were made available which were used to dig the holes to set the corner posts (photo 04).

04 Hand Held Post Hole Digger Over time though, fence building has become significantly easier using materials of more durability. Although I didn’t go into farming as an occupation, twenty years ago I fenced a seventeen acre field using metal posts with woven wire below and barbed wire above (photo 05).

05 Woven Wire Metal Post The metal posts were driven into the ground with a cylinder hand held driver (photo 06).

06 Metal Fence Post Driver No heavy sledge hammer was needed. The only wood used was for the corners where I used old telephone poles for the posts and bracing. Also, instead of a hand held manual post hole digger, I had the advantage of a large drill hooked to a three point hitch and used the PTO of the tractor to power it to dig the holes for the corner posts (photo 07).

07 Three Point Hitch Digger The metal posts are about the only kind of fence support used these days. You hardly ever see wood post fencing on working farms nowadays. Also, since fencing now is mostly used to contain cattle, the woven fencing which was used for keeping in hogs isn’t so much needed so you don’t see much of that anymore either. In Miller County presently, I am told that specialty crews often are used to put up fencing using hydraulic post drivers for the metal posts (photo 08) and five strands of barbed wire without any woven wire involved (photo 09).

08 Hydraulic Driver

09 Metal Post Barbed Wire Fence Another interesting innovation now is the use of used pipe from the oil fields for the corner posts. These fencing crews are so well equipped and efficient that hiring them saves the busy farmer time and money, I have been told.

You can look at some interesting videos of modern fence building at this website:

http://www.redbrand.com/installation/

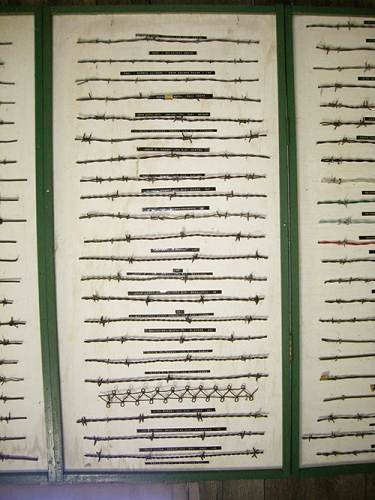

I was reminded of fence building last week as we rearranged our farm implement and tool display at the museum. One of the displays in the exhibit is a collection of barbed wire designs (photo 10) which was donated by A. H. Stephenson who used to live off Highway 52 between Tuscumbia and the Highway 54/52 junction.

10 Stephenson Barbed Wire Collection in Farm Display Mr. Stephenson was not a native of Miller County but lived in this area about thirty or more years ago having bought the old John Farmer farm located on Woods Road. Mr. Stephenson had been collecting barbed wire specimens for many years including around our county. Brice Kallenbach, who was raised not far from where Mr. Stephenson’s farm was located, said that many times he had seen Mr. Stephenson walking over one of the surrounding farms looking for pieces of broken fence wire. I knew that barbed wire had become an item for collectors but I never knew just how complicated the subject was until after I began to spend some time studying Mr. Stephenson’s collection. Quite a few of the wire strands in the display are from Miller County but Mr. Stephenson did not classify them by location.

It was very nice of Mr. Stephenson to donate his life’s work of this collection to the museum and for that reason I wanted to learn more about him. What I learned was sad due to a number of situations which occurred near the end of his living here. I obtained the following information from Elmer Brown, who was born and raised near where Mr. Stephenson lived:

Joe,

I knew Mr. Stephenson only slightly.

My sister Marie died on January 9, 1986 after a very short illness. Immediately after her funeral my sisters Kathleen Martin and Jean Voorhees and I were in the process of sorting things out and putting her farm on the market. By this time the original home (photo 10a) had been replaced by a more modern one (photo 10b).

10a Original Brown Home Place

10b Second Brown Home Coincidently, the Stephenson's house on the Farmer place burned to the ground one evening while they were in Eldon for dinner and shopping. This left them with nothing more than the clothes they were wearing and no place to live. I can't remember who put us in touch but we struck a deal and they bought the farm lock stock and barrel. This included my sister's clothes and we kept only a few keepsakes. They lived there for several years but I can't tell you how long.

My only direct contact with him was when he came to look at the place and I walked him around the land and buildings. I didn't know anything about his being a barbwire collector. My recollection is that Mrs. Stephenson was not in good health at the time and she preceded him in death. I seem to remember hearing that at some point after her death he went to live with a son or daughter in the Chicago area.

Thanks for the information, Elmer. It is unknown to me at this time whether the collection had been donated to the museum before or after this fire.

Here is another closer look at one of the display boards of barbed wire collected by Mr. Stephenson (photo 11).

11 Barbed Wire Sections In order to show the huge number of different designs of barbed wire on these display boards I had to stand too far back to show some of the intricate designs.

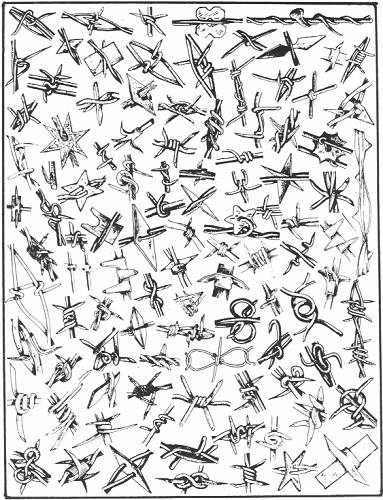

However, here is a diagrammatic collage without description of a number of the different barb designs which have been used in the past (photo 12):

12 Barb Collage Photo After getting into the subject of barbed wire I was surprised by how many different types had been made through the years regarding the type of barb used. I looked into the history and found a website which in detail covers the subject of barbed wire history. You can locate it yourself at this URL:

http://www.barbwiremuseum.com/index.htm

I will summarize from the site some interesting information. First, here are some facts about the barbed wire made in 19th century America:

1. There are over 570 patented wires to search for in acquiring a collection.

2. Over 2,000 variations of these patented wires have been found and cataloged to date.

3. Less that 50% of the patented wires were manufactured commercially because of difficulty in producing the wire with automated machinery, or excessive costs in manufacturing.

4. Less than 10% of all patented wires proved to be practical in actual use. Those wires not produced in quantity, become rare and sought after by collectors.

5. In the final analysis, the Glidden patent #157,124 issued in 1874, and the Baker patent #273,219 issued in 1883, were the most practical and successful.

Here is another collage of the many designs used for barbed wire in the past with more descriptive detail:

691B. C-543, G-127, B-77, A-559, J46, ( )

Scutt Single Clip "H" Plate

Two twisted strand wire with four point "H" barb. Barb is fastened to one strand with a metal clip. Patent #205,000, June 18, 1878 by Hiram B Scutt of Joliet, Ill. |

204B. C-235, G-340, B141, A-180, ( )

Dodge Six Point Star Barb

Single strand wire with six point sheet metal star barb. Strand is enlarged on each side of barb to prevent movement. Barbs may or may not rotate. Patent #250,219, Nov. 29, 1881 by Thomas H. Dodge of Worcester, Mass. |

693B. C-573, G-129, A-562, ( )

Scutt Arrow Plate

Two twisted strand wire with four point sheet metal arrow plate barb. Barb is split and shaped like an arrowhead. Variation of Patent #205,000 as per wire #691B |

194B. C-213, G-140, B-49,A-442, J-50, ( )

Knickerbocker Applied Three Point Barb

Single strand wire with a three point hand applied barb. Barbs could be bought by the pound and hand applied. Patent #185,333, Dec. 12 1876 by Millis Knickerbocker of New Lenox, Ill. |

730B. G-818, A-414, ( )

Hodge Spur Rowel on Large & Small Strands

Twisted large and small strands with ten point sheet metal spur rowel barb. Variation of Patent #367,398, Aug 2,. 1887 by Chester A. Hodge of Beloit, Wisc. |

920B. C-811, G-236, B-123, A-78, J-126, ( )

Brinkerhoff Face Clamp Barb

Flat sheet metal ribbon with two point sheet metal clamp-on barb. Barb plate is cut so that barb can be bent around ribbon. Patent #241,601, May 17, 1881 by Jacob & Warren M. Brinkerhoff of Auburn, N.Y. |

860B. C-704*, ( )

Cady Barbed Link, Double Wrap

Folded single strand link with ends joined in center of link by double wrap to form two point barb. Variation of Machine Patent #292,408, Jan. 22, 1884 by Frank P. Cady of Chicago, Ill.

|

155B. C-148, G-110, B-50, A-464, J-51, ( )

Merrill Four Point Twirl

Single strand wire with four point barb. Patent #185,688, Dec. 26, 1876 by John C. Merrill of Turkey River Station, Iowa |

34B. C-72, A-355, ( )

Glidden Hanging Barb

Single strand wire with two point hanging barb. Variation of Patent #RE 6913, Feb. 18, 1876 by Joseph F. Glidden of De KaIb, Ill.

|

138B. C-144, G-7, A-367, ( )

Glidden Square Strand

Single square strand wire with four point coil barb. Patent # RE 6914, Feb. 18, 1876 by Joseph F. Glidden of De Kalb, Ill. |

35B. G-596, B-8, A-351, ( )

Glidden Round Single Strand

Round single strand wire with coiled two point barb. Patent #RE 6913, Feb. 18, 1876 by Joseph F. Glidden of De KaIb, Ill.

|

570B. G-216, A-424, ( )

Jayne & Hill Locked Staples& Wood Block

Two twisted strand wire with wooden block warning device and four point barb around both strands. Patent #176,120, April 11, 1876 by William H. Jayne & James H. Hill of Boone, Iowa |

408B. G-1032, ( )

Glidden Large Square Strands

Two large square twisted strands with two point barb on one strand. Patent #157,125, Nov. 24, 1874 by Joseph F. Glidden of De Kalb, Ill |

914B. G-93, A-75, ( )

Brinkerhoff Opposed Lugs Lance Point

Flat ribbon wire with two point lance point applied barb. Patent #214,095, April 8, 1879 by Jacob Brinkerhoff ofAuburn, N.Y. |

567B. C-481,G-349, A- 422, ( )

Jayne & Hill Locked Staples Around One

Two twisted strand wire with four point barb on one strand. One leg of barb straddles other strand. Variation of Patent #176,120, April 11, 1876 by William H. Jayne & James H. Hill of Boone, Iowa |

638B. C-506, C-98, A-428, ( )

Kelly Thorny Common

Two twisted wire strands with two point sheet metal thorny barb. Patent #74,379, Feb 11, 1868 by MichaeI Kelly of New York, N.Y. |

Collecting Barbed Wire

Usually barbed wire specimens are collected in 18” lengths to show the spacing between the barbs. Due to space limitations, some collectors acquire specimens in 4” to 6” lengths to show the barb design only. Most collections are mounted on display boards with patent information shown in neat labels as well as occasional comments about the wire.

The Mystique of Barbed Wire Identification

Some confusion may occur in wire identification for several reasons:

1. Early day patent office procedures allowed wire patents to be filed in several different categories making the patent information and design detail difficult to find.

2. Raw stock smooth wire purchased from the steel mills often varied in uniformity both in size and shape because of die wear and wire content ingredients.

3. Wires made by blacksmiths, small co-op groups, and non licensed manufacturers were often intentionally made slightly different in design to circumvent patent infringement.

4. When the crude automated manufacturing equipment of the time began to wear, odd marked barbs and line wire appeared. Machinery malfunction created varieties of originally design.

What did ranchers and farm owners do before barbed wire?

Here is what the site listed above has to say:

Many historians believe one of the defining moments in the history of the West came when a small bunch of wild longhorn steers stopped and backed away from eight slender strands of twisted wire equipped with sharp barbs. This event happened in 1876 when John W. (Bet-a-Million) Gates erected an enclosure on the Plaza in San Antonio, Texas to demonstrate to gathered ranchers, that newly-invented barbed wire could securely contain wild livestock. From that moment on, the West would never be the same again.

This defining event ended the era of open range and the use of free graze which had reigned supreme since the earliest settlers began to populate mid-America. At that same time, new technological inventions and modern manufacturing equipment and processes grew by leaps and bounds providing the start of the Industrial Revolution across America.

Post-war demands for beef here and abroad, new railroads available for livestock transportation and the invention of refrigeration spawned the greatest cattle boom in the history of the new nation. The cattleman was king and his domain seemingly unending.

However, the moment those longhorns stopped at the wire in San Antonio, the age of the pioneer, free-range cattleman was doomed. No one foresaw how drastically barbed wire fencing would eventually transform western life at that time and on into the future.

Surely, the changes required a few hectic and sometimes bloody years in transformation, but as inevitable as sunrise the vast ranges from Mexico to Canada were slowly claimed and their boundaries fenced with wire. The greater the adversity met in claiming and fencing the land the greater the pride-of-ownership in the land by the owner.

An interesting side note about the early-day livestock business is, before the Civil War, stealing cattle and horses was virtually unknown. Wild cattle, mustangs and free land were nearly everywhere free for the taking so why risk the chance of theft and punishment if caught.

Some believe that because in the Civil War invading armies virtually lived off the land by plundering and taking what they needed to continue, this created a new class of renegade and raider without conscience who was cruel, cunning and arrogant.

The Republic of Texas became the refuge of the renegades as they deserted military service before and immediately after the war ended. The absence of law, millions of square miles of wild terrain for hiding and the easy prey of scattered pioneer homesteads made outlaw living easy. For a time, these renegades threatened the very existence of settlers in some areas and became more dreaded than the wild Indians roaming the land.

Eventually, their atrocities brought vigilante groups and the Texas Rangers whose actions pushed the renegades into Kansas and Indian (Oklahoma) Territory. A few recorded interviews with these renegades after capture revealed the one thing that curtailed their thieving activities the most was the presence of barbed wire fences. The actual theft, movement of stolen livestock and escape after a crime was committed became much more difficult because of these fences of barbed wire strung along property lines.

Here is an abbreviated history of barbed wire taken from the website given above:

Before Barbed Wire

Since the beginning of time, man has constructed his barriers from natural materials adjacent to the barrier site. These materials were mostly wood from trees, stone, thorny brush, and mud. When settlers arrived on the Great Plains of America, they found these materials in short supply, thus creating a demand for a more economical type of fencing.

Smooth Wire Development

Dating back to 400 A.D., the process of pulling hot, bloom iron through dies in a drawing plate produced short lengths of various sizes of smooth wire. By 1870, good quality smooth wire was readily available in all sizes and lengths. Stockmen used the smooth wire in fencing but found it was not a dependable deterrent to livestock passage.

The Invention of Wire With Points

In 1867, two inventors tried adding points to the smooth wire in an effort to make a more effective deterrent. One example was not practical to manufacture, the other experienced financial problems. In 1868, Michael Kelly invented a practical wire with points which was used in quantity until 1874.

The Invention of Barbed Wire

Joseph F. Glidden of Dekalb, Illinois (photo 13) attended a county fair where he observed a demonstration of a wooden rail with sharp nails protruding along its sides, hanging inside a smooth wire fence.

13 Joseph Glidden This inspired him to invent and patent a successful barbed wire in the form we recognize today. Glidden fashioned barbs on an improvised coffee bean grinder, placed them at intervals along a smooth wire, and twisted another wire around the first to hold the barbs in a fixed position.

The Barbed Wire Boom

The advent of Glidden's successful invention set off a creative frenzy that eventually produced over 570 barbed wire patents. It also set the stage for a three-year legal battle over the rights to these patents.

The Father of Barbed Wire

When the legal battles were over, Joseph Glidden was declared the winner and the Father of Barbed Wire. The aftermath forced many companies to merge facilities or sell their patent rights to the large wire and steel companies.

Accepting the Devil’s Rope

When livestock encountered barbed wire for the first time, it was usually a painful experience. The injuries provided sufficient reason for the public to protest its use. Religious groups called it "the work of the devil," or "The Devil's Rope" and demanded removal.

Free range grazers became alarmed the economical new barrier would mean the end of their livelihood. Trail Drivers were concerned their herds would be blocked from the Kansas markets by settler fences. Barbed wire fence development stalled.

The Fence Cutter Wars

With landowners building fences to protect crops and livestock, and those opposed fighting to keep their independence, violence occurred requiring laws to be passed making wire cutting a felony. After many deaths, and uncountable financial losses, the Fence Cutter Wars ended.

Need and Promotion Triumph Over Opposition

A demonstration in the Military Plaza in San Antonio by John "Bet a Million" Gates, proved beyond a doubt barbed wire was durable and successful in controlling livestock. With his expertise in salesmanship, he eventually became the largest stockholder in American Steel & Wire Company and a legend in barbed wire history.

The Last Straw

The last opposition fell when the large ranches in Texas began fencing their boundaries and cross fencing within. Among the first to fence were The Frying Pan Ranch, The XIT, and the JA Ranch, all located in the Texas Panhandle.

Preservation of and Collecting Barbed Wire

There are over 530 patented barbed wires, approximately 2,000 variations and over 2,000 patented barbed wire tools to collect as well as advertising, salesmen samples, wire cut medicine bottles, and other wire related items.

The way cattle travel naturally without the barrier of fencing is something I hadn’t thought about (except for the fact that the farmer has to have some way of keeping his cattle on his property). However, the website listed above has some interesting comments in this regard:

Livestock, if left on their own, are lazy and relaxed. They travel only to find new graze or to drink and move slowly always on the lookout for a tasty morsel of grass. Since climbing uphill is work and going down steep slopes hurts their feet their natural path is usually the easiest path.

The rolling prairie lands of the west are marked by cow trails appearing almost as arteries leading to and from windmills and water holes. Old Tascosa, the second oldest town in the Panhandle of Texas was established at the converging trails formed by Buffalo who found an easy crossing on the treacherous Canadian River.

Cow trails often appear to run on gradient lines as if laid out by professional surveyors using transit tools. In steep areas the trails switch from side to side choosing a less demanding path using less effort and energy. Rough canyons usually have a clear path showing the easiest access.

The narrow winding cow paths are formed by the hoof action and sharp toes which tend to loosen dirt particles. Others following smash the particles into dust which is carried away by wind and rain runoff. The toes seem to flip small gravel and rock out to each side of the trail and out of the beaten path.

When rainfall occurs, the runoff enters these miniature contoured terraces, picking up the dust and carrying it to eventual disposal. Over a period of time the formerly shallow trails become arroyos and gullies showing extreme erosion.

What has all of this got to do with barbed wire? A simple deduction tells us barbed wire follows boundaries. Boundaries are laid out in grids. The nature of the terrain crossed by these boundaries is hardly ever considered when devised.

In contrast, livestock follow the contours of the terrain seldom traversing steep hills and sharp inclines. When barriers force them from the natural contours the results are trails going downward sharply contributing to swifter erosion.

Another problem is that the nature of livestock is to pace out the parameters of their domain, especially newly-placed animals. This pattern causes trails to be formed parallel to fences where normal travel should not occur. Observance from the air reveals almost all pasture fences are well marked by eroded parallel trails on both sides of the barriers. Old fences long removed, can be easily traced by these markings.

In areas more susceptible to erosion, fences lines are often destroyed by ever-deepening ditches. Many rural roads and right-of-way fences require continual maintenance because of erosion started by cattle trails. The problem continues to worsen each year.

Yes, no doubt barbed wire fences have had, and are still having a negative impact on the land. Though serving magnificently in keeping livestock under control the sharp barbs force the cow to change from her natural instincts in laying out a trail along a contoured level. As a result, the land has suffered.

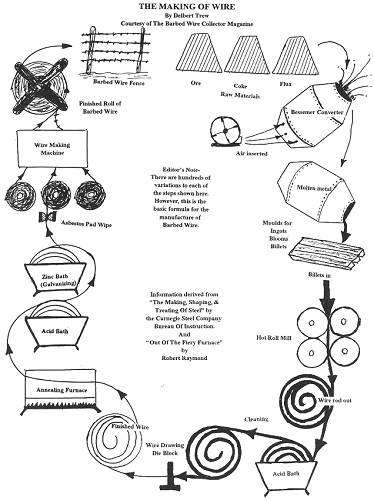

The following is a description of the history of the process by which the wire for the barbs was made:

In the 1850s architects and engineers were beginning to push against the limitations of iron used in construction. Cast iron was cheap but too brittle for many construction forms. Wrought iron was superior but expensive and inconsistent in quality and strength.

A new solution was needed. According to most history books this solution was found in 1856 by English engineer Henry Bessemer (photo 14).

14 Henry Bessemer Instead of stirring and puddling molten iron by hand to bring the impurities to the top for skimming, Bessemer tried blowing air into the bottom of the converter hoping to float the impurities to the top. He thought the process might fail because the inserted air might cool the molten metal.

In his first experiment, when the air was applied the result was extremely violent. The exothermic reaction generated heat in the molten iron instead of cooling as he had predicted. The converter erupted with flaming gasses and sparks for about ten minutes before subsiding. When Bessemer tapped the molten metal into the moulds, he found he had produced a malleable or workable product, which was virtually wrought iron. This announcement of his discovery was proclaimed to be the most momentous industrial innovation of the century. Amazingly, Bessemer's process used no fuel, actually increased the temperature of the molten metal, and was fast in nature. The age-old puddling process required two hours to produce a product where Bessemer's process took twenty-five minutes. This breakthrough unleashed the full energies of the Industrial Revolution throughout the world. Bessemer was proclaimed a hero for his efforts and the process was named after him.

The true story of the development of the Bessemer Process is told in the history of the steel industry. This story verifies the fact the perfecting of a process is seldom accomplished by one mind alone but by several minds working towards the same goals.

The idea for the Bessemer Process announced in 1856, was actually formulated in 1847 by William Kelley of Eddyville, Kentucky. Kelley built a converter at Jamestown, PA with provisions for inserting air through ducts into the molten metal for puddling. However, he lacked the finances to complete the experiment. After Bessemer applied for patents on the process in 1856, Kelley also made application and was able to prove prior claim by reason of his converter built in 1847 at Jamestown.

Only after much controversy and a generous settlement, did Kelley drop out of the picture allowing Bessemer to receive the patents. Under these patents, Bessemer built a plant at Sheffield, England in 1860. The first Bessemer Process plant in the U.S. was erected in 1867.

The new process was not without problems especially in consistent quality of content of the metal produced. A major remedy was found by Americans Thomas & Gilchrist by improving the lining and bottom of the converter. To operate at top efficiency in production, Bessemer's plants needed radical revisions in design. Alexander Holley an American Engineer, introduced many of the needed improvements. A new model of a converter with a detachable bottom and interchangeable drums allowed the equipment to produce around the clock without stop. A hot metal pre-mixer, developed by W. R. Jones of the Carnegie Steel Company, speeded up the process and allowed assembly line production.

With all due credit and respect to Henry Bessemer, many professionals both in England and the U. S. contributed to the development and the refinement of the new processes needed to meet the increasing world demands.

The journey of molten metal into a finished product is long and sophisticated in nature with hundreds of varied alternatives available depending on the requirements of the finished product. In an effort of simplification, the following descriptions and illustrations will pertain only to wire used in the making of barbed wire.

As the Bessemer Process is completed, molten metal is poured from the converter into various sized moulds. These include Ingots, Blooms, Slabs, and Billets depending on their size, weight, and final configuration. Each will be rolled or pressed into near final design as quickly as possible taking advantage of the first heat left over from the converter.

Smaller Billets, formed from Ingots, are used in making wire rod. The white hot Billets are run through a hot roll mill which eventually produces various size wire rod wound in 30" coils weighing from 150 to 300 pounds per coil. Wire rod for making fine wire will be of #8 gauge. Rod for common wire is of #5 gauge.

While these wire rod coils are considered the finished product of the hot roll mills, it constitutes the raw product to be used in the wire mills and should be considered the first step in the making of wire.

Steel history states the Washburn & Moen Manufacturing Company is responsible for many innovations in the manufacture of wire. By 1870, the company had developed a continuous wire rod mill allowing for unlimited production of wire and had begun development of automatic reels needed to speed up production. In the making of wire rod, it is necessary for each individual operation of the process to be as near perfect as possible. This includes metal content, and proper temperatures while pouring, rolling, and treating. Any variation may cause defects, which are magnified as the wire rod starts into the drawing dies.

There are many classes of finished wires including nail wire, telegraph and telephone wire, fence and rope wire, spring and musical wire and hundreds of miscellaneous and specialty wires. Almost all of these products are made from the wire rod coils. To meet the specifications of these wires requires different methods of coatings, heating, tempering, drawing, and finishing.

For fence wire we will describe the low carbon wire rod. The first step in wire drawing is cleansing the scale, rust, and dirt from the coils by bathing the coils in a hot dilute sulfuric acid for 15 to 30 minutes. After rinsing with water, the coils are dipped into vats containing hot milk of lime leaving a whitish coat that is baked onto the wires for protection and lubricant. The coils are now placed on a wire drawing frame where a sharpened end is inserted through the die block hole and attached to the draw reels of the draw block. The wire rod is pulled through the die blocks reducing its size and extending its length. The reduction in size is known as draft and is expressed in percentage of original rod size. This draft or reduction in size is usually 10% to 45% per drawing. Fine wires require several drawings to reach the desired finish gauge.

Processes used in wire drawing include wet and dry drawing. Methods used are single draft drawing and continuous drawing. Both process and method used depend on requirements of the finished product. These requirements also affect the finish on the

literally hundreds of coatings which are available.

If the wire is required to be ductile, soft, or pliable to any extent, annealing is necessary. The general purpose of annealing may do any or all of the following:

1. Softens the wire for machining.

2. Relieves internal stresses and strains induced by forging, rolling, or drawing.

3. Removes coarseness of grain thus improving strength, elasticity, and ductility. Annealing is usually done by passing the wire through ducts in a furnace or by passing it through molten lead. The wire is now of the proper size and has been annealed.

The next step is Galvanizing for protection. A good lasting job of Galvanizing can be accomplished if the wire is clean and both the Zinc and wire is the same proper temperature at the time of the coating. Cleaning is again done with an acid bath and the wire is drawn through molten Zinc until it reaches the proper temperature for the coating to adhere. As the coated wire leaves the Zinc bath the wire is wiped smooth between two Asbestos pads and is spooled again ready for the next step in manufacture.

The Galvanized smooth wire is now ready to enter the barbing and twisting machine. Single strands of wire from three different spools enter the machine. One strand is used to make barbs attached around another single strand. As the barbed strand leaves the machine it is twisted together with the third strand and wound on the final product spool complete with metal name tags ready for shipment and sale. The process of manufacturing barbed wire seems complicated and difficult. Today, modern machines, thermostat-controlled heaters, automated sensors, and computer controlled assembly lines manufacture wire products quickly and economically with predicted quality.

(Note - These processes were used from the late 1800s until more recent times with continual modernization both in physical and mechanical means taking place annually. Modem day processes may vary from those described herein.)

Here is a diagram of the process of the manufacture of galvanized smooth wire (photo 15).

15 Diagram of Wire Making

Click image for larger viewNo doubt the preceding was more than you ever wanted to know about barbed wire! But for some people, such as Mr. A.H. Stephenson, collecting barbed wire specimens amounts to quite an interesting hobby; and no one can dispute that the invention of barbed wire allowed a radical change in the practice of letting cattle free range, especially as ranches and farms became smaller with many different owners involved.

In the Progress Notes for March 16, 2009 I copied an old article from the Tuscumbia Autogram detailing the construction history of the building of the new bridge across the Osage River in 1933 which replaced the old suspension bridge of 1905.

In that story the tragic death of Avery Baucom was reported. Here is copied the paragraph which describes the event:

“One fatal accident occurred during the erection of the bridge. On July 23rd, Avery Baucom of Eldon, a structural steel worker, fell from the top of pier 9, in midstream, struck the top of a sheet piling 60 feet below, then rebounded into the river, ten feet lower. The body fell across a rope, and was recovered by George Davis, just as it began to sink. Baucom had worked on the job only 30 minutes when he apparently stepped off the top of the pier after he had been tightening a nut on a bolt through a steel beam. He died a few moments after he fell.”

The event was reported separately in the Iberia Sentinel as follows:

The Iberia Sentinel

July 1933

Avery Baucom of Eldon was killed in a fall from the middle pier of the bridge under construction at Tuscumbia, Monday morning about 7 o’clock. Baucom had just been employed as a steel worker and had worked only about one half hour when he lost his balance while at work on the high middle pier and plunged downward. His body struck the steel piling which had not been removed after the completion of the concrete pier and he was almost immediately killed.

Workmen who were working nearby stated that when Baucom apparently lost his balance he tried to jump clear of the construction work so that he would alight in the water but he hit a brace which threw him back causing him to light on the piling. The fall was from a height of about 62 feet. After hitting the piling he fell into the water and fellow workmen rescued him before he sank. His right side hit the piling and crushed his lungs badly. Dr. Kouns was immediately called but Baucom died within a few minutes without regaining consciousness.

Baucom leaves surviving him a widow and two small children.

It occurred to me that this tragedy must have been very sad for Avery’s family at the time and I would imagine that those close to him would have had a difficult time during those days of celebration of the bridge’s opening. He was a well known young man at the time. My cousin, Sandra Bear Shelton, originally from Eldon told me after reading the story that her father, Arthur Bear, had known Avery as a friend when both worked in the Bagnell area and remembered he “was a very good boxer.” Sandra also remembered her mother, Lena Brown Bear, had a friend who probably was Avery. Here is what Sandra had to say:

“Mom had a boy friend (before she met dad, of course) that went by the name of HAPPY. She never told me his legal name, but he worked on the dam. When it was finished, she said that Happy moved to Tuscumbia to work on the bridge there, and he fell off the bridge and was killed. Mom said that he was a “rigger” who did specialized work in high places, and that’s why his fall was fatal. So, I'm wondering if the Avery Baucom that you mentioned in the article, was her friend Happy. Guess we'll never know, but I believe that he 'boarded' with grandma Bear at the Goosebottom house.”

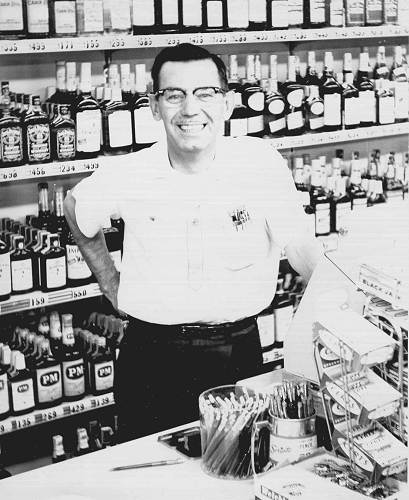

Because of these bits of information here and there I decided to find out more about Avery. So I called Jeanne Baucom of Eldon (photo 16) and she graciously allowed me to come to her house to obtain more information about Avery.

16 Jeanne Baucom Avery, Jeanne told me, was the brother of her husband, Bob Baucom, who passed away several years ago. She confirmed that Avery was a “rigger” having learned that in the Navy. She said a rigger usually worked with a partner and that they had to be very skilled at working in high places such as on a navy sail boat, one of those with multiple masts and large sails. Jeanne also said that Avery’s son, also named Avery, had joined the Navy at a young age and also died at a young age of a sudden death. Because of that, the family wondered if Avery the rigger really had not slipped that day on the bridge at Tuscumbia but possibly suffered a sudden death of cardiac origin since his own son later on had also suffered an unusual sudden death.

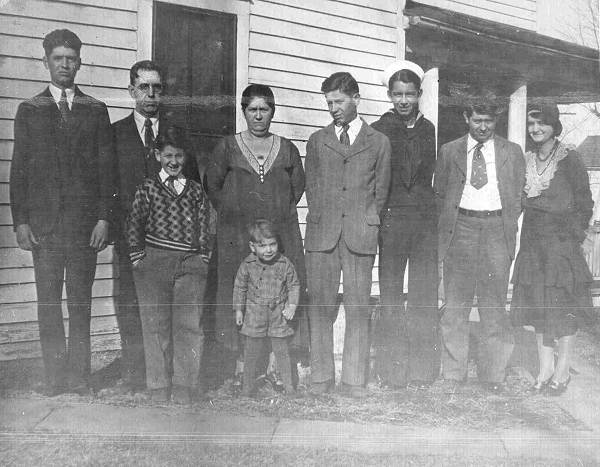

Jeanne showed me a family photo (photo 17).

17 Baucom Family:

Back Row:

Avery, Avery Leander, Mae Elizaeth, Robert Francis, Richard Earl, Roy Isaiah, Dorotha Mae

Front Row:

Harry Lee and Clarence In this photo, Avery the rigger is on the far left and his father, known as Avery Leander (Lee for short), is next to him. The others in the photo are Mrs. Baucom and other members of the Baucom’s children. One of the children of Avery Leander in the photo is Roy Baucom (number 6 in the back row), whom some may remember as having worked at Reed’s clothing store in Eldon for many years.

Avery’s father, Avery Leander, worked for the railroad and belonged to the “Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen, Lodge 690, Gasconade District.” Bob Baucom, husband of Jeanne, was a good friend of Bob Richardson. Bob Richardson was very well known around Eldon for his witty writing skills, especially well displayed in his book, “Up the Caboose,” which was about life in Eldon back in the early part of the last century, with an emphasis on the railroad industry. Bob’s father spent many years as a conductor on the railroad. Bob Richardson sent Bob Baucom (brother to Avery and husband of Jeanne) this photo of the members of the “Brotherhood” (photo 18).

18 Brotherhood of Railroad Trainmen Lodge 690 - Gasconade District - 1910

Click for larger imageIn the photo Avery the rigger is the young boy in the middle and to his left is his father, Avery Leander. The others in the photo were partially identified by Bob in this note (photo 19).

19 Brotherhood Names (Note: For an example of Bob Richardson’s writing go to this previous Progress Notes and scroll down the page about half way.)

Sometime after the photo above was taken, Avery Leander lost his right arm in an accident and had to retire from heavy railroad work. He is standing on the far left in this photo and one can see that he is wearing a prosthesis (photo 20).

20 Avery Leander - Lee Baucom on Left So I was happy to be able to provide more information about Avery Baucom and his family so that his accidental death in 1933 while working on the new bridge will not be forgotten. I am grateful to Jeanne Baucom, wife of Avery’s brother Bob, for letting me spend some time with her the other day to learn more about the Baucoms’ and Avery.

Jeanne and I enjoyed discussing her family as well. Her father, O.L. (Bo) Huckabay, who was a “Master Carpenter,” brought Jeanne and the family to Old Bagnell so that he could work for Union Electric while the dam was being built. One memory of Jeanne’s of personal interest to me was that she remembered taking vegetables from her mother’s garden where they lived near Bagnell and walking to my grandfather Madison Bear’s general store which was located on the main street in Bagnell. Madison, Jeanne said, would give her a few cents for each vegetable which he would sell to customers in the store. She remembered the big Bagnell fire which burned Madison’s store as well as several other buildings in the early 1930’s. You can read about the Bagnell fire(s) at this previous Progress Notes from last year.

Scroll down the page to near the end to get to the part about the fire which destroyed Madison’s store.

After the dam was completed Jeanne’s family moved to Eldon where she completed high school. Sometime later she met Avery Baucom’s brother, Bob Baucom, whom she later married (photo 21).

21 Bob Baucom - Brother to Avery and Roy She had become good friends with Bob Richardson, to whom I referred above, and he is the one who encouraged Bob to strike up a relationship with Jeanne. However, the marriage to Bob was delayed since he was in the Navy then and he told Jeanne they couldn’t marry until his mother had passed away since he was her only financial support. Bob, like his brother Roy, also worked for Ralph Reed as a home deliverer of grocery phone orders to customers in the Eldon area. I told Jeanne that I remembered Roy Baucom working in Reed’s department store but never knew that Ralph at one time had a grocery store in Eldon in addition to his clothing store. I didn’t remember seeing her husband Bob during those days when I would come up to Eldon.

So thus ends the story about Avery Baucom, the young man who suffered a tragic death falling from the new bridge across the Osage River at Tuscumbia during its construction. As Paul Harvey used to say, “Now you know the rest of the story.” And I am happy to have been able to present this very belated followup to Miller County residents about Avery and his family.

Layne Helton and his crew surprisingly, considering this wet spring, recently has made some very visible progress on the huge job of removing rock on the south side of the river for the new road entrance to the new bridge. Connie Prather sent me some good photos of the work being done. First, here is a shot from the south bluff looking down the river before rock removal began (photo 22).

22 Looking Downriver Next is a shot looking down at the old bridge (photo 23).

23 Looking from Bluff to Bridge And this photo shows one of the heavy shovels beginning the task of cutting off the top of the bluff (photo 24).

24 Beginning to Remove the Bluff Top Here is a shot from the north bottom ground showing the beginning of the laying of the road bed (photo 25).

25 Creating New Roadbed And finally, here is a shot from the Autogram last week giving a closer look at how much of the south bluff hilltop has been removed (photo 26).

26 More Bluff Removal

Our next potluck dinner is scheduled for this coming Sunday, April 19, 1:00 pm at the museum in our new lower level meeting room. This week we have as a special speaker MCHS member Dwight Weaver. Dwight, who is a member of our museum committee, is a recognized author of four books having to do with the Lake area commercial history. He has just finished the fourth book about the lake area entitled “History and Geography of Lake of the Ozarks VII.” In addition, Dwight has had a long history exploring and writing about Missouri caves having written six books about that experience. Here is a photo of Dwight and museum director Nancy Thompson in front of a bookcase displaying Dwight’s books (photo 27):

27 Dwight and Nancy Thompson discussing Dwight's Books Dwight came by the museum this week to assist in the creation of a new museum display featuring more than fifty of his vintage Lake area photographs taken of some of the earliest businesses and resorts which were located in Miller County after the Lake was created (photo 28).

28 Dwight with his Lake Photo Collection In addition, Dwight donated a collection some of the many souvenirs sold by the early gift and souvenir shops during the 30’s, 40’s and 50’s in the Lake area (photo 29).

29 Lake Souvenirs of the Early Years Collected by Dwight That's all for this week.

Joe Pryor

|