|

Monday, July 25, 2011

Progress Notes

Next week, August 3rd, will be the 205th year anniversary of the encampment of the Zebulon Pike expedition at Tuscumbia during its exploration of the Osage River in 1806 as part of our government’s mapping of various areas of the Louisiana Purchase.

I don’t suppose many people will be celebrating the event but I thought I would present some narratives this week about Pike and his exploration party. We have covered the story of Pike previously on our website fairly thoroughly at these URL’s:

- Miller County History Links

- Progress Notes of August 16, 2010

Where Tuscumbia now is located was a very good site for river boat landings which probably explains why the Pike expedition chose it for that particular day, August 3rd, 1806 for its nightly encampment. Here is Miller County painter John Wright’s artistic rendition of how he imagined the Pike entourage appeared (photo 03).

03 John Wright's painting of Pike's Landing at Tuscumbia

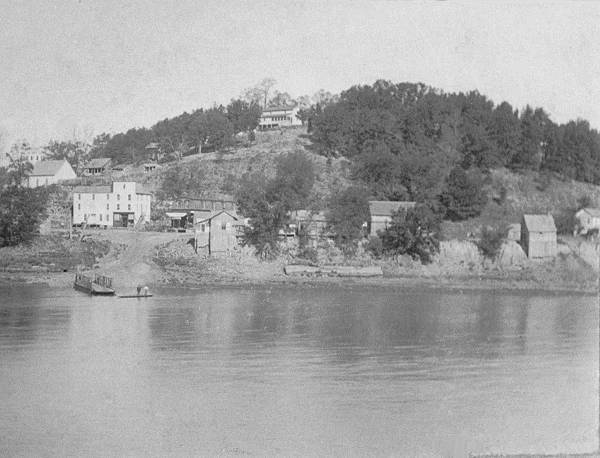

The same area was used years later as a ferry landing and for steamboats which loaded and unloaded supplies and goods (photo 04).

04 Ferry Landing at Tuscumbia looking North across the River

And even today, the landing is a Missouri Conservation Department river access for fishermen and others who bring their boats for fishing and water recreation on the river (photo 05).

05 River Landing

Pike wrote an entry for his diary every day of the expedition. I presented in a previous Progress Notes more detail about Pike’s passing through our area based on information from Pike’s diary as reported in an article in the Autogram in 1931 by historian Gerard Schultz:

“One of the most famous American explorers traversed what is now Miller County. In 1803 the United States purchased from France the region extending from the Mississippi river to the Rocky Mountains. As little was known of the geography of the newly acquired territory, several expeditions were sent out to explore it. One of the most notable of these was the southwestern expedition of Zebulon M. Pike.

On July 10, 1806, expedition started up the Missouri river at Fort Belle Fountains, a United States military post located on the south bank of the river, four miles above its mouth. Pike was accompanied by one lieutenant, one surgeon, one sergeant, two corporals, sixteen privates and one interpreter. He also had under his charge fifty one Indians of the Osage and Pawnee tribes. The United States government had redeemed these Indians from captivity among the Potawatamies and they were to be returned to the villages of their tribes on the Osage River. On the morning of July 28, the mouth of the Osage River was reached.

After three days journey up the Osage the party camped on the eastern bank of the river in the vicinity of the present day village of St. Thomas, situated in the southeastern corner of Cole County. The last day of July, Pike entered what is now Miller County. A study of Pike’s narrative and map seems to show that the party passed the present site of Tuscumbia on August 3.

The following record was made on that day:

“3d August, Sunday: Embarked early and wishing to save the fresh, (in other words, to take advantage of the high stage of water in the river) I pushed hard all day. Sparks was lost, and did not arrive until night. We encamped about twenty five paces from the river on a sandbar. Near day I heard the sentry observe that the boats had better be brought in, when I got up and found the water within a rod of our tent, and before we could get all our things out it had reached the tent. Killed nine deer, one wild cat, one goose, and one turkey. Distance eighteen miles.”

August 6, the expedition passed the mouth of Gravois creek in Morgan County, Pike writes,

“About three miles above this river (Gravois Creek) the Indians left us and informed me that by keeping a little to the south and west they would make in fifteen miles what would be at least thirty five miles for us.”

At the time the southwestern expedition of Zebulon M. Pike ascended the Osage in 1806, no settlements had been made along this river. Before the United State government sold land to private persons, it was surveyed into rectangular tracts, six miles square, called congressional townships. The north boundary of township thirty nine north of the base line range twelve west of the fifth principal meridian was the first government survey made in this county. This line was surveyed by Joseph C. Brown in 1816.”

Noted historian Edwin W. Mills wrote an article about Zebulon Pike’s exploration of the Osage River valley for Missouri Magazine which later was reproduced in the Miller County Autogram. No photos accompanied the article but Mr. Mills flowery artistic style of writing will evoke an occasional mental image as you read it:

Pike’s Expedition Up The Osage 1806

Edwin W. Mills

The Miller County Autogram

August 18, 1937

(originally published in “Missouri Magazine”)

Missourians who love to let fancy roam backward to the picturesque pageantry of America’s early cavalcades, who have gazed on the majestic grandeur of Pike’s Peak as it lifts its snow clad summit far above the clouds and have wondered whence its name, come with me to the great dam at Lake Ozark or to the bluffs at Warsaw where a beautiful community house of glistening limestone will soon become a landmark for the surrounding valley.

Let us dream here a strange picture of the long ago when a pair of rude river craft and their motley crew and savage passengers laboriously traveled up the Osage River in the midsummer of 1806. This novel and picturesque expedition was under the command of an aspiring young officer, Zebulon M. Pike, the son of a revolutionary soldier. Sometimes in sight of the boats, and again obscured by the cliffs and woods, there followed on foot along the course of the stream a number of braves and youths of the Osage and Pawnee tribes.

Picture this stream in those early days as being clear and beautiful, its lower waters winding among wooded hills, and cedar capped bluffs, its upper branches reaching out like tentacles to drain wide, grassy prairies to the west---primeval plains which knew only the noiseless tread of the Indian’s moccasin, the thundering hoof beats of innumerable buffalo and the swift feet of Indian ponies, antelope and deer. For these fertile prairies lay uncultivated as they were still to lie for nearly half a century, unscarred by the crude iron point of the settler’s wooden plow shear.

Up this stream in the blistering July sun, one hundred and thirty years ago, strong men whose rough uniforms marked them as United States soldiers were slowly and laboriously working a large flat boat or barge and a smaller boat resembling a large river skiff or canoe called a “bateau”.

Pike in his diary does not give the dimensions of these crafts, but the larger one if not the identical boat which he had used the year before in his expedition to the upper Mississippi, was no doubt of similar size and type. That boat he had described as seventy feet long. The mast, which he had used on this previous expedition and was again using, was a pine spar he had secured in Minnesota. This mast was discarded after it had been found impractical in navigating the Osage. When thrown into the latter stream it bore the names of Pike and several of his men which had been carved upon it, thus showing that these men, even on this early pioneering expedition, did not lack for sentiment.

Various methods were used in working the boats up stream. Now the crews leaped overboard and “cordelled” the boats, wading the riffles or walking along the bank as they pulled the long tow ropes; again, where the conditions were unsuited to this process, they labored at the oars or paddles, or, using long poles they grounded themselves in the river bed and ranged on both sides of the barge. Facing aft, they leaned against the boats and with a walking, tread mill motion, slowly forced them up stream; at other times before the mast was discarded, when wind, current and direction permitted, they hoisted a square sail on the flatboat and took advantage of every available force of nature to speed their voyage.

One who has rowed an ordinary skiff loaded with camping paraphernalia…guns, dogs, ammunition, tent and camp supplies…against the strong current of the Missouri river may have some appreciation of the enormous amount of labor performed by Lieutenant Pike and his men in making their usual ten to fifteen miles each day.

Following the boats and trudging along the banks and over the bluffs were a number of Indian men and boys, the squaws, papooses, and less hardy members of the Indian band remaining in the boats; for in the expedition, under the protection of the American soldiers, were fifty one Osages and Pawnees whom, under orders from General Wilkinson, Lieutenant Pike and his soldiers were escorting to the Indian villages near the head waters of the Osage River. These Indians had been in captivity among the Pottawattomies and were being restored to their relatives and friends.

In Lieutenant Pike’s company, which, after completing the escort of the Indians, was to explore and map the valleys of the Arkansas and Red Rivers and to cross the plains to Santa Fe and the southwest on a mission of conciliation among the Indians, where a physician, Dr. John W. Robinson, an interpreter who could speak English, French and Spanish, and Lieutenant James Wilkinson, a son of General Wilkinson. There were twenty three white men in all. A day or so after the expedition had left Fort Bellefontaine, four miles above the mouth of the Missouri, a private named Kennerman deserted, reducing the number of privates in the expedition to fifteen. The company had started from the fort, a military post four miles above the mouth of the Missouri, on July 15, 1806, and reached the mouth of the Osage River on July 28.

The Indians did not camp with the white men, but they were given much of the game that was killed on the trip. The weather was too hot, of course, for it to be preserved, and doubtless the Indians were not at all particular in the matter. Several bear, numerous deer and turkey were killed by the party. Much of this game was brought down by Lieutenant Pike who was a fine rifle shot and successful hunter.

We may well fancy the varied pictures that this expedition presented…the primitive silence of the river broken by the shouts and songs of the men, and the orders of the captain as he directed them. Now and then a leaping fish breaking the surface of the stream; in the riffles schools of startled minnows turning on their sides, flashing for an instant like shapeless mirrors then vanishing; turtles, great and small, basking on protruding snags in the summer sun, startled by the unaccustomed intrusions slipped or fell clumsily into the water. Blacksnakes and moccasins disappearing among the piles of driftwood, only to appear a few yards away with outstretched heads and beady eyes, wriggling for safety to the farther shore. Again, a herd of deer might be seen slaking their thirst at the rapids, whirling about in instinctive alarm and scampering into the forest wilderness at the first scent of danger. Occasionally one of these might be brought down with a well aimed shot thus securing a contribution to the food supply of the camp.

At intervals Indian camps were passed, and a week or more before reaching the Osage River the party had left the last important settlement of the whites “Les Petit Cotes” (St. Charles), far behind as they had worked their way up stream.

The Pike expedition must have reached the vicinity of the Lake of the Ozarks early in August. The primitive methods used necessarily meant slow progress, and after entering the Osage with its tortuous windings among bars and drift piles, their strenuous exertions were only slightly eased, if at all.

In spite of the heartbreaking toil of river travel, it was a light hearted company that passed up the stream. The Indians must have anticipated with unfeigned joy their reunion with kindred and friends. The frontiersmen doubtless looked forward with pleasurable anticipation to their great adventure over the unmapped plains toward Mexico, little dreaming of the terrible ordeal which they were within a few brief months, to be subjected to…days and nights of bitter cold and gnawing hunger, on one occasion going for four days without a mouthful of food until their commander was fortunate enough to bring down a buffalo. In the vastness of the icy Rockies and shelterless, they were to suffer cold so biting and intense that many of their feet were frozen; in the case of one man the bones protruded and came out, but all were saved, miraculously as it were, form tragic death.

The Osage was not a total stranger to the river craft of the white man. For probably half a century the exploration loving French “voyageurs” had paddled their bateaux up this stream to trade for furs with the Osage Indians.

Comparatively little trouble with these Indians was experienced by the pioneers of Missouri, due to the great influence wielded over them for years by the Chouteau brothers, Auguste and Pierre, Sr., who had learned the Indian language in boyhood in St. Louis and whose headquarters for their great fur business had been established in that city before the Revolutionary War.

They had established a trading post about 1783 on the Osage River at what is known as Holley’s Bluff, some nine miles across the prairies below the great Indian village. Pike’s diary mentions passing some French cabins and later the site of Chouteau’s fort, but comments that “not a vestige of it remains.” He evidently referred to the building itself, for the cache pits may still be seen in the sandstone bluff. This trading post had been abandoned, doubtless, as the beaver, mink and otter grew scarcer and as the St. Louis fur trade reached farther and farther up the Missouri and to the Rocky Mountain country.

These trading posts were doubtless of a similar type. The last of them was described by Richard F. Elliott, the “Tree Apostle of Kansas,” whose last resting place is in the beautiful Oak Hill Cemetery at Kirkwood. He had been appointed Indian Agent at “Blacksnake Hills,” the trading post of Joseph Roubidoux (now St. Joseph, Missouri) in 1843.

In his “Notes Taken During Sixty Years” he describes it thus: “The warehouse was a building of stockade fashion, split logs set upright and roofed with clapboards, with the weight poles over. On its earthen floors were stored sugar, coffee, salt and other merchandise, together with the household furniture and miscellaneous plunder of the incoming settlers, and some barrels of that prime necessity of civilized frontier life, Bourbon whiskey.

In the Indian band were two chiefs. One of them was Big Soldier, a brave of the Little Osages. More than once he had been to Washington to see the Great Father. Another of the band was Sans Orielle (“Without Ears”), so called because of his refusal to listen in council to the younger braves. Pike had no little trouble in keeping the Indians under his control and in preventing petty thievery around the camp by his dusky charges. On one evening the Osage Chief, Big Soldier, was displeased with Sans Orielle and some of the others who had left him. He started to flog Sans Orielle’s squaw, but was prevented by Pike and his soldiers.

These Indians doubtless were without the usual adornments and weapons of their tribe. No necklaces of teeth and bear claws, no ornaments of mussel shells or silver, no bows, arrows or lances did they possess, for they had been held in captivity by the Pottawatomies who doubtless took from them every thing of value in the eyes of a savage. Only the joy of anticipated reunion with their kindred prevented them from presenting a squalid and forlorn appearance.

When the evening shadows began to fall across the river the boats were moored at a suitable spot and the crew and passengers disembarked. Doubtless they were soon joined by the Indians who had been traveling afoot, they to make their own amp in primitive fashion and the white men busying themselves with their own preparations for supper and for the night.

We may easily fancy the delight of the Indian children at being liberated from the confinement of the boats, and that they ran and played among the trees or splashed in the water. Doubtless, too, they hunted among the gravel bars for mussels, craw fish and turtle eggs for their evening meal. We can picture, too, the squaws gathering wood and bending over the campfires in the gloaming, as primitive women have done since the twilight dawn of human history.

Then as the lengthening shadows gave relief from the summer sun and the dusk of evening fell, the toil stained men bathed in the stream and the hunters returned to camp. Odors of the camp smoke, baking corn pone and roasting venison, floated in the evening air. Later, the camp supper being finished, soaked clothing hung to dry and the freshly killed game skinned and cared for in the light of the flickering campfires, cooling night fell over the sun parched landscape and the stars appeared, reflect in the dark, rippling surface of the river.

After the evening smoke of red men and white, the bantering jests and jibes of the white men contesting with the guttural grunts of the Indians, tired limbs and aching muscles quickly relaxed in sound repose. Sentries strode slowly back and forth upon their beats with their long rifles in hand. No sounds were heard save the hooting of owls in the forests, the metallic buzzing of insect life, the crying of an Indian babe, or the guttural croaking of great frogs in the nearby sloughs as they harshly replied to the spasmodic chirping of nature’s animated barometers…the tree toads of the virgin woodland.

Throughout the night the dying embers of the forest camp fires were kept covered with leaves and trash from the forest bed in order to create smudges about the camps to combat the ever present mosquitoes.

So must have passed the long nights of the journey.

But each breaking day brought resumption of the laborious tasks of the expedition. With the first faint streaks of dawn the sleeping life of the river and valley awoke. As the mists from the river vanished and the dank odors of rotting vegetation faded before the magic of old Sol, outlines of the bluffs, cedars, forests, winding stream and gravel bars took on their familiar shapes. From the forests sounded the melodies of a thousand songsters…catbirds, thrushes, vireos, cliff swallows, martens, and a host of other feathered maestros.

“Then from the neighboring thicket the mocking bird, wildest of singers,

Swinging aloft on a willow spray that hung o’er the water,

Shook from his little throat such floods of delirious music,

That the whole air and the woods and the waves seemed silent to listen.”

But in crude incongruity with this heavenly morning chorus, doleful wails, outcries and lamentations began to come from the Indian camp. For an hour or so the savages each day in this strange fashion lamented their departed relatives and friends, mourning and crying until the tears flowed down their cheeks; then, this daily barbaric performance having been religiously accomplished, they quickly emerged from their sorrow and gloom and began to go about their daily tasks contented and smiling as though their grieves and tribulations were things apart.

The wailing of the Indians having died away, far up on the overhanging bluff, as though enchanted by the beauty about him, a Kentucky cardinal from the crest of a gnarled cedar, whistled his liquid melody with seraphic sweetness. As though to challenge his fiery vanity, an oriole flashed down across the stream like a golden bullet, his flight reflected for a moment in the water beneath him giving the impression of a darting gold fish.

Far above the travelers a she bear panting in the heat but now and then lazily clawing at fleas, looked questioningly down from behind a clump of cedars and roughly boxed her too inquisitive cubs back into their ill smelling den.

By this time the sun was well up above the horizon and both camps were astir, preparing their simple breakfasts of venison, bear meat, corn bread and coffee. After a short interval of satisfying their hunger and enjoying a brief smoke, camp was broken, the boats reloaded, all but the Indian walkers embarked and the toilsome journey was resumed.

And so the voyagers passed up the Osage, the young commander determined and imperative but sharing all of the hardships. Faithful to his trust, in due time he delivered to their tribes and homes the little band of these simple children of forest and plain, to carry out, in their primitive lives the unfathomable purpose of the Creator.

From his narrative, General Pike was one of the most successful hunters and probably the best rifle shot in the company. That their journey lay through a hunter’s paradise is revealed by the amount of game which he reports as killed. From the time the expedition left Fort Bellfontaine until it reached the Osage River, a period of thirteen days, members of the party had killed six deer, two bears and ten turkeys, besides other game.

While on one of his brief hunting excursions, General Pike almost stepped upon a large rattlesnake, but, as it did not strike, he considerately spared its life.

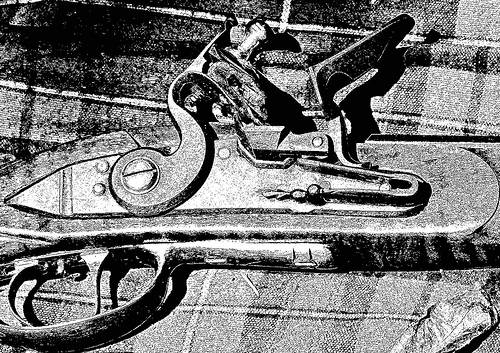

In his diaries, the young commander of the expedition up the Osage makes only brief mention of the shooting match which he won. The weapons used were the long, heavy flintlock rifles of the Kentucky type (photo 15).

15 Kentucky Flintlock

Identical with the pattern used so effectively by the riflemen of Kentucky and Tennessee at the Battle of New Orleans six and a half years later, when, of the hundreds of redcoats who fell before the murderous fire of the frontiersmen with General Andrew Jackson, fifty per cent were shot through the head.

The reader may wonder why Pike, who had suffered severe privations on his expedition to Minnesota the year before, would under take his journey to the southwest at this belated time of the year. The late start caused his expedition to reach the Rocky Mountains and the Royal Gorge of the Arkansas River in the midst of a bitter winter when both he and his men for weeks daily faced death by starvation and exhaustion.

The explanation of this apparent blunder lies in the fact that General Wilkinson had planned this expedition should be conducted by another officer, but on Pike’s return to Fort Bellfontaine from his northern journey General Wilkinson importuned him to take the lead in this fresh venture into the Southwest. With the true respect of a soldier for the wishes of his superior officer, Lieutenant Pike complied without question. But it was, in the light of subsequent events and privations, a very serious blunder…the same blunder that the luckless Donner party made during the days of the gold rush, when they loitered along the plains country and did not reach the Sierras until after heavy snow had fallen. ‘There they were compelled to camp, snowbound, inaccessible to rescuers and unable to go on. What had been few months before a happy, hopeful caravan of pioneers, under the stress of cold and starvation became a camp of insanity, cannibalism and death.

While the Pike expedition was on its tedious way up the Osage River, notable events were transpiring in the East.

The returning Lewis & Clarke Expedition which had crossed the plains and Rocky Mountains to Oregon, was slowly nearing St. Louis. A Shawnee brave, Tecumseh, from the valley of the Wabash, was emulating the great Pontiac who had been assassinated across the Mississippi and whose body had been brought to St. Louis and buried there. Like him, Tecumseh had dreams of uniting the Indian tribes of the middle west in a confederacy to expel the whites.

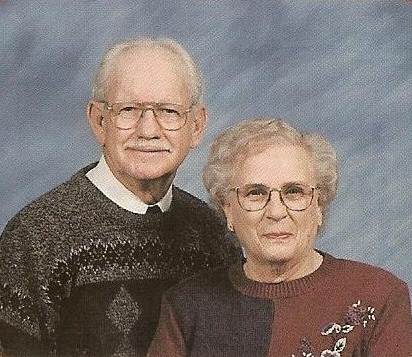

Not long ago I was visiting Jack Jones at his home in Eldon to do some guitar and mandolin picking (photo 17).

17 Jack and Peggy Jones

While there I noticed a painting on the wall of a well built and attractive home (photo 18).

18 Painting of Home

Jack told me it was the Charles Myers home located between Iberia and Brumley. Jack said the home was built by his great grandfather, Charles Myers Jr. and that he had taken a photo of the home to an artist who was an inmate at the Jefferson City State Prison where Jack worked at the time. The artist worked on the painting off and on but after the better part of a year finished it and since then, about twenty years ago, Jack has had it hanging on his wall. Jack said that his grandfather was William Myers. His mother, Maggie, was a daughter of William. Her brother, Astor Myers, had married Cleo Abbett, who was a sister to my grandmother, Sadie Abbett Bear.

I had remembered that there was something special about this house so I looked it up on our website and discovered it had been featured on the site.

Here are a couple of photos of the house taken from the website (photos 19 and 20):

19 Charles Myers Home

20 Charles Myers Home - 1992

Peggy Hake wrote the article for the above website about the home as well as the Myers family which built it and lived in it.

I will copy from Peggy’s article some interesting information about the home:

The home sits in the Hickory Point community, near Brushy Fork Creek in Richwoods Township. An old road once led out of Iberia, crossed the Barren Fork, turned west and passed by the old Hickory Point Church and school, then turned northwestward and crossed the Brushy Fork near the Myers home. The log house, built about 1867, was unique and rare to our part of the country in those years. The style was known as a double-pen log house. They had been prevalent in the countryside of the eastern states prior to the Civil War. The structure was two log cabins interconnected to form one house. They were built 10 to 20 feet apart with a common roof built over the space between.

In 1820, a man named Zerah Hawley, while visiting in Ohio, wrote with wonderment of this type of home. He said in the space between the two log units was…"placed the swill barrel (table garbage for the animals), tubs, posts, kettles, etc. Here the hogs almost every night dance a hornpipe to a swinish tune, which some one or more musicians of their own number play upon the pots and kettles, while others regale themselves in the swill barrel."

Other names given this type of structure include "dog-trot house", "dog-run house", "possum-trot house", "two pen and a passage house". These names were applied mainly in the states of Georgia and Tennessee.

One unit was usually used to serve as a kitchen and living room while the other was used as a bedroom. The covered passageway formed an area for family activities in the summer and a cool veranda on a hot summer's night. Each cabin had its own fireplace for winter's heat and year-round cooking.

This type of house was widely distributed in the early American settlements and later, in our country's history, the dog-trot house found its way to Texas and other western states. While researching this extraordinary type of log house, I found another way it was used. Frontier doctors often used these breezeways between the units to "purge, bleed, blister, and salivate" their patients in order to bring on the "shakes", believed to cure anyone suffering from ague (a violent fever). One pioneer doctor wrote in his journal that he "suggested to a family that they carry the patient into the passageway between the cabins, strip off his clothes that he might lie naked in the cold air upon the bare sacking, and then pour upon him successive buckets of cold spring water and continue until he had a pretty powerful, smart chance of a shake!"

As families increased in size, rooms were added to the top of each cabin with stairways on the outside. The only heat these bedrooms had was what could filter and drift up from the floor below. At times, it must have been bitterly cold because in Miller County we have had "Arctic blasts" from the North converge upon our peaceful countryside…Oh! How comfortable my 20th century home.

Thanks Peggy.

When you come to our museum be sure and visit our own “dog trot home” which is a very good replica of this type of structure used often in the Ozark hills and other areas more than a century ago.

That’s all for this week.

Joe Pryor

Previous article links are in a dropdown menu at the top of all of the pages.

|