|

Monday, January 9, 2012

Progress Notes

This week I am going to present a very good article from the magazine, The Waterways Journal, about the history of steamboats on the Osage River. Probably, most of that history has to do with steamboats owned by business men in Tuscumbia, but not all, especially early on in the history of Osage River waterway navigation. The article was well researched by author James V. Swift and was published in 1984:

The Osage Is An Important Missouri River

The Waterways Journal

February 25, 1984

By James V. Swift

The Osage River is a main tributary of the Missouri which enters that river below Jefferson City, Mo., at Osage City. It has always been of interest, but it was made more so one day when the writer was enjoying the hospitality of Captain Paul Striegel at his Lake of the Ozarks home near Linn Creek. He pointed out the window and said, “You know, that’s where the steamboats used to land.” On the next trip down in that country, stops were made at Linn Creek to visit the Camden County Historical Society and Tuscumbia, Mo. to visit the Miller County Historical Society.

For some brief Osage River history, the stream’s drainage basin comprises some 250 square miles. There is in the Waterways Journal files a list of Osage River landings by William Towns, who was a pilot on the Osage for 30 years, which shows Schell City, 298 miles up from the Missouri. The first, or one of the first steamboats on the Osage was the North St. Louis, which entered the river the last week of July, 1837 (she also grounded about 30 miles from the mouth, and is commemorated by North St. Louis Island). The first steamer built for the Osage trade was the Maid of the Osage at Osage City.

City of Tuscumbia

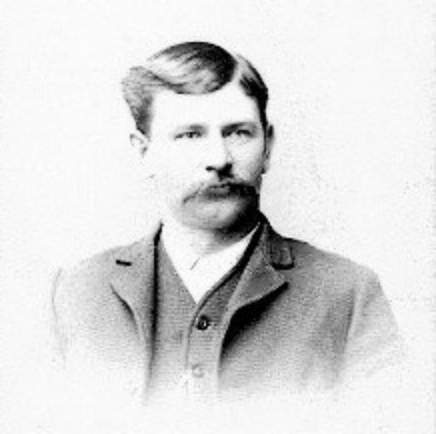

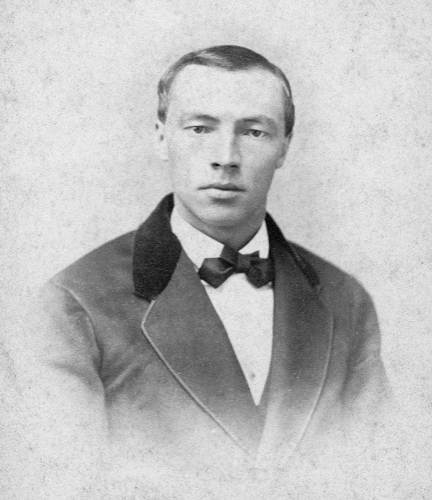

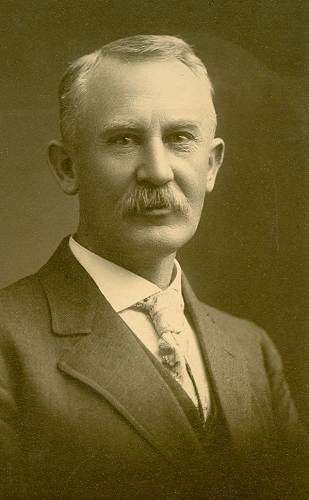

We will begin this series at Tuscumbia, Mo., home of several well known Osage River steamboat owners and operators, such as Captain Robert M. Marshall and William H. Hauenstein (photos 01 and 02).

01 Robert Marshall

02 William H. Hauenstein

The next picture shows Tuscumbia with the river landing and buildings up the hill (photo 03).

03 Steamer Frederick at Tuscumbia Landing

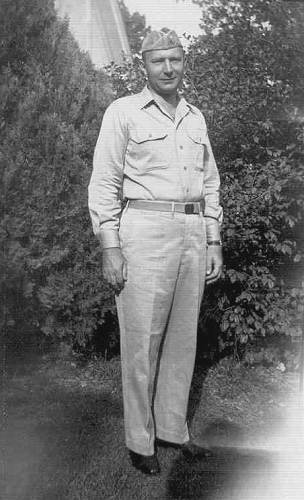

Fortunately, the Miller County Historical Society is a viable organization at Tuscumbia, with an interesting museum in the old jail behind the courthouse. It was closed when we went there, but Mrs. J.H. (Nova Humphrey) Land opened the museum for us and it is to her that we owe this picture (photo 04).

04 Nova Humphrey, Oma Graves and Harry Lee Graves at South Side Station Tuscumbia 1940-41

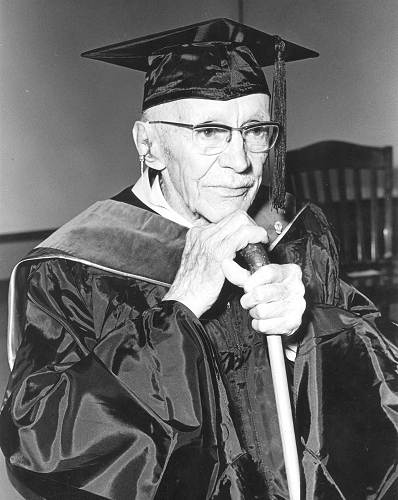

The Frederick had been built in 1883 by Captain W.H. Hauenstein under the supervision of Joseph Shepherd, an expert boat builder, who had designed the hull. It was made of burr oak and was 96.4 by 14.3 by 3 feet. She was registered at 82.51 net and gross tons, and the engines were 7 ½ inches in diameter, with a 2 ½ foot stroke. Captain Hauenstein operated the Frederick a short while and then sold a half interest to Captain Marshall, who was his brother in law. She had come out with a single deck, but after Captain Marshall bought into her she was given a cabin deck for passengers. (The boat was named for Captain Hauenstein’s son, Frederick, whose mother had drowned after falling into the Osage River from another steamboat) (photo 05).

05 Frederick Hauenstein at 75th Alumni Reunion Westminster College

The pilot was Captain Henry Castrop who reported in a series of articles for the “Miller County Autogram Sentinel” in 1931 that the cabin made the boat top heavy and hard to handle in the wind (photo 06).

06 Henry Castrop

The engineer was a Mr. Grant and his assistant, Charles Jenkins.

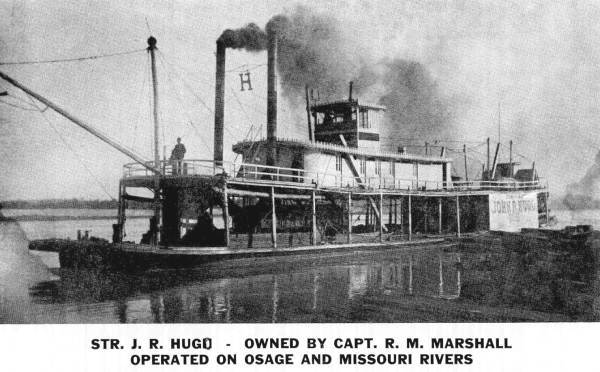

The Frederick could not handle all the business, and Captain Marshall bought the steamer John R. Hugo and barge Jumbo (photo 07).

07 Steamer Hugo

The Frederick sank at Jefferson City August 10, 1894. The knuckle or butts sprang a leak; the guard caught on a barge and machinery was removed. The Frederick also towed a barge named the Alma.

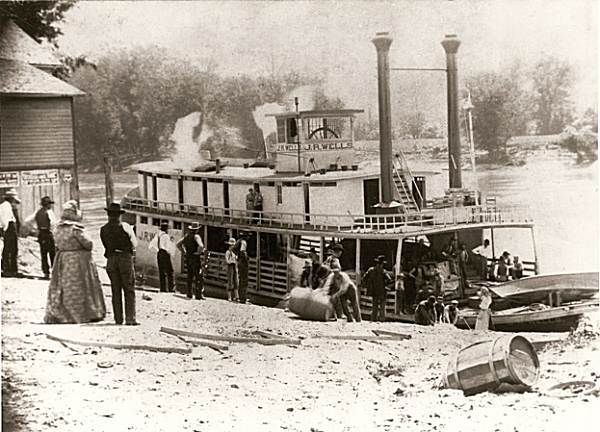

Another boat from Tuscumbia was owned by the Anchor Milling Company and named for the head of the firm, J.R. Wells (photos 08 and 09).

08 J.R. Wells

09 J.R. Wells Steamboat

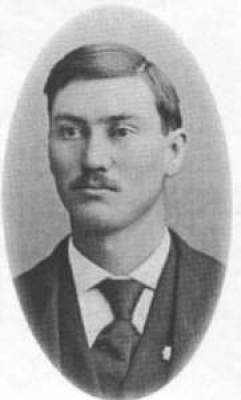

The vessel was built at Tuscumbia in 1897 with a hull 110.6 by 20 by 4 feet, and engines 10 inches in diameter with a 4 foot stroke. Captain John W. Adcock was the boat’s first master and pilot (photo 10).

10 John W. Adcock

The Miller County Historical Society at Tuscumbia has some interesting material from the Anchor Milling Company and in a newsletter dated June 17, 1983, carried a picture of the Wells and some information from records kept by its clerk, C.B. Wright, which his son, Homer C. Wright, has preserved (photos 11 and 12).

11 Clarence Wright

12 Homer C. Wright

Towed a Barge

The J.R. Wells also towed a barge in which was carried livestock. Her cargo included produce going to St. Louis and everything from coffins to corn planters up bound. Mr. Wright recorded one interesting item, a basket of laundry from Linn Creek to the Ivan Laundry in Jefferson City, Mo. (the charge was 25 cents).

In 1906 the Wells made 31 trips between January and December, with a few temporary tie ups due to low water. Landings included Linn Creek, Zebra, Bagnell, Tuscumbia, Tellman’s, Blankenship’s, Huhman’s, Capp’s, Ben Sanning’s, Tapperhorn’s Warehouse, Morman’s, Schyler’s, Mueller’s, Bisgel’s, Feise’s, Castle Rock, Westphalia Landing and Osage City.

Became a Tow Boat

The J.R. Wells eventually became a tow boat and worked for the Rust & Swift Contracting Company in St. Louis among many others. She was owned by Stanton & Jone Contracting, Leavenworth, Kansas, when she sank in Pelican Bend near St. Charles, Mo., on the Missouri river, January 30, 1920 (the writer has always had a warm spot in his heart for the J.R. Wells, inasmuch as she was in the pictures his father had of river operations…pictures often looked at when the family was far away from the river in New Mexico.)

Referring again to the loss of the Wells, she had been tied up for the winter and as the ice broke up, it tore her loose. She rapidly drifted into the main channel where she was crushed, turned turtle and sank in deep water.

Our thanks for the picture of the Wells go to Mrs. J.H. (Nova Humphrey) Land and the Miller County Historical Society.

Other Boats Built At Tuscumbia

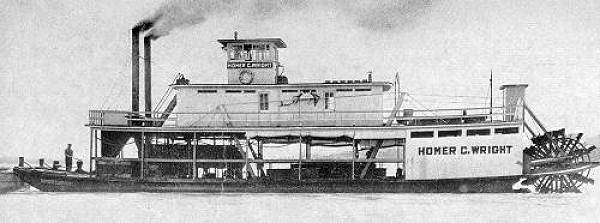

C. B. Wright wrote in one of his diaries that “Our steamer Homer C. Wright was the last of the steamers built for the Osage River packet business (photo 13).

13 Homer C. Wright Steamboat

This last we built here at Tuscumbia in 1919 and sold to the Union Electric Company in 1924. The Wells steamboat was put in commission in April 1898 and was operated by our company until 1909. During the 10 years interim between the sale of the Wells in 1909 and the building of the Homer C. Wright, we operated a gas boat called the Ruth, so that we were as a company continually in the boat business, steam and gas, from 1898 until 1924. The writer acted in various capacities on each of them, rouster, clerk and pilot on the Homer Wright.”

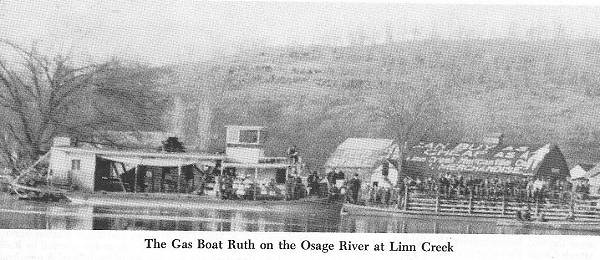

The Ruth, built at Tuscumbia in 1908, was 52.5 by 12.2 by three feet and had 25 hp. Her registered tonnage was 13 gross and 8 net, and she had a crew of two. As can be sen in the picture, the Ruth towed a barge just as her sister steamboats had done (photo 14).

14 Steamboat Ruth at Linn Creek

As you can see, the Ruth must have carried excursions. Also, from the appearance, age wise of the passengers, we would say it was a church or school group aboard (it is also interesting to note that the Linn Creek Mercantile Company took advantage of outdoor advertising). The Ruth is shown as being abandoned in 1925.

Also found in our Osage River file was a story from the “Appleton City, Mo. Journal” telling of the terror raised among St. Clair County, Mo. residents when the first steamboat with a “wildcat” whistle came up the Osage. This was the Flora Jones in 1844. She got all the way up to Harmony Mission in Bates County because of high water, and on the trip she blew that whistle every few miles; the local inhabitants thought it was a giant animal of some kind. They mobilized and started searching the riverbank, but of course, the Flora had gone on up the Osage. What really confounded the hunters was that their dogs couldn’t or wouldn’t pick up a scent, and there was even talk of sending somebody to St. Louis to buy new and more interested dogs.

To make a long story short, the Flora came back down, using her whistle frequently, and the intrepid hunters headed for a cave and safety. When the Flora shot into view, with her decks full of passengers enjoying the sunrise, the hunters heard another piercing scream from the whistle as the boat passed from view around the bend. As the writer for the newspaper put it, “the picture of that band of old pioneers, standing there, their rifles still on their shoulders, and their faces looking as if petrified, was a scene for a painter, and Barnum could have made a fortune.”

Some Other Boats

“Judge Jenkins’ History of Miller County” gives names of other Osage river boats, including the North St. Louis, Maid of Osage, Chouteau Belle, Wave, Little Jack, Adventure, Leander, Agatha, Huntsville, Warsaw, Emma, Alliance, Reliance, Linn Creek, Belfast, Navigator, Regulator, Umpire, Thomas E. Tutt, Last Chance, Otter, and Cora.

Linn Creek Was Important Landing On Osage

On our voyage up the Osage River in Missouri, which we began at Tuscumbia, our next destination is Linn Creek. Here lived another man who was important to navigation on that stream and also to Missouri state politics. Joseph W. McClurg was elected to Congress for three terms and was governor of Missouri from 1868-70 (photo 15).

15 Joseph Washington McClurg

However, he was also a merchant of great stature and used Osage River boats for the distribution of goods from ports on that river throughout this area of Missouri and even into Arkansas. From Warsaw, Mo., for instance, near the head of navigation on the Osage, tons of freight were distributed through a region of equivalent to 15 counties.

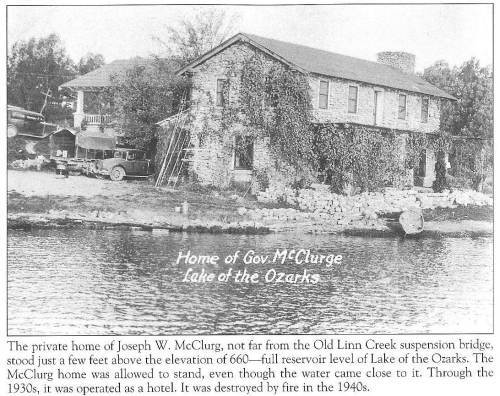

Governon McClurg built a fine home near Camdenton, Mo., in 1854, and it later became a resort hotel (photo 16).

16 McClurg Mansion - Dwight Weaver

He died in 1900 and is buried in the Lebanon, Mo. cemetery. Governor McClurg was active in getting the Osage River improved and so we shall hear more of him in future stories.

Owned and Chartered Boats

According to “Judge Jenkins History of Miller County,” Judge McClurg owned the Emma, Alliance, Mary C. and Linn Creek boats, and chartered other boats to move goods for him down the Ohio. In 1858, some 13 steamboats arrived at the Linn Creek landing from St. Louis with goods valued at well over $8,000.

It is recalled that Judge McClurg was a deeply religious man who tied up his boats from midnight on Saturday to midnight on Sunday. He was also much interested in improvements on the Osage, and he used the Emma in some snagging and dredging operations. We will report more on that later.

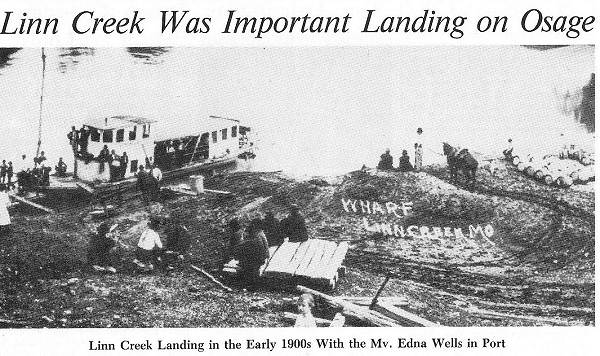

Linn Creek Landing

The following picture of the Edna Wells steamboat was taken at the Linn Creek landing in the early 1900’s (photo 17).

17 Edna Wells Steamer at Linn Creek

One of the important features here was that it was close to the junction of the Osage with one of its principal tributaries, the Niangua. As I mentioned before, you can see this landing from the home of Captain Paul Striegel.

The gas powered Edna Wells, which is classified as a freight boat in the list of merchant vessels, was built at Kansas City, Kansas in 1908. She was 54.4 by 11.5 by 3 feet, and is rated at 24 hp. She had two in the crew according to the merchant vessel list.

The Edna Wells had a short life. She burned at Linn Creek on June 22, 1910, but we don’t have any details.

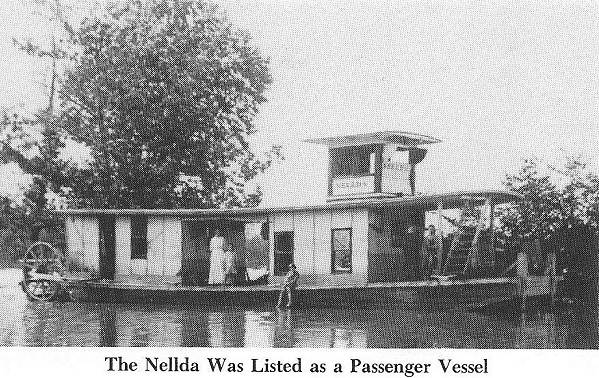

The Nellda

In our continuing saga of Missouri’s Osage River, we have today a picture of another boat that ran there, the Nellda (photo 18).

18 Nellda at Linn Creek

Of special interest is the fact that she was built at Linn Creek. She was built there in 1914, with dimensions of 50.1 by 11.2 by 2.2 feet. Horsepower is shown as 36 and tonnage 8 gross and net. The vessel was registered for passengers and a crew of one. Unfortunately, there isn’t much more information on the Nellda, except that she ran until 1921; she is shown as “abandoned” in the 1922 list of merchant vessels. The boat may also have towed from the appearance of the scow, bow and small knees. We wonder if the lady or the little girl may have been the “Nellda for whom the vessel was named.

Earlier in this series we had mentioned and expressed appreciation to Mrs. J. H. (Nova Humphrey) Land for her help at the Miller County Historical Society at Tuscumbia, Mo. For much of the Linn Creek material we are indebted to Mrs. Neva O. Crane and Mrs. Thelma Parish, who opened the Camden County museum for us one morning. It is a very interesting museum in the old school at Linn Creek, with diverse items on display, including Osage River pictures showing log and lumber rafting.

Thanks to Mrs. Crane and Mrs. Parish, we were directed to Camdenton, Mo. nearby, and there saw Mrs. R.W. Vincent who had some Osage River pictures. To her we are indebted for several photos we had never seen before; we arrived ahead of time, but even so Mrs. Vincent allowed us time to take them outside and make copies.

And thanks to these ladies, we wee directed still further away to Lebanon, Mo., and Mr. Victor Jeffries, who also had some Osage River pictures. He is particularly interested in Linn Creek and wrote a very interesting story about the old town which is now at the bottom of the Lake of the Ozarks.

When the immersion took place, as we understand it, the former citizens split up, so to speak, with some establishing a new Linn Creek while others moved to Camdenton.

Of special interest to us in the journal by Mr. Jeffries was the account of one of Linn Creek’s leading merchants, John James, who made a number of trips to St. Louis in the interest of his business. Unfortunately, he was on the steamer Kate Kearney February 16, 1854, when she blew up at St. Louis. Mr. James was one of the six known dead in the accident. We wrote to Mrs. Parrish to see if his body had ever been recovered and, perhaps, returned to Linn Creek for burial. She replied that she had talked to Mrs. Emma Phillips, great granddaughter of Governor McClurg, who said according to her knowledge the body was never recovered.

The name John James is familiar along the Missouri River since there was a towboat named that; she was owned by the Massman Construction Company between 1931 and 1940. We don’t know if there is any connection between the Linn Creek merchant and the namesake of the towboat.

The final chapter in the Osage River history regards how the stream was maintained so the steamboats and gas boats shown in this article could run up and down the river.

The importance of the river was recognized early. It was on February 11, 1839 that the state of Missouri’s General Assembly created a State Board of Internal Improvements whose main duty was to survey and issue a report on what could be done to make them navigable streams. A survey on the Osage was completed August 2, 1940, with the shoals and rapids enumerated from Osceola to the Missouri River. On December 20, 1840, the board issued its first and last report. Other rivers surveyed were the Meremec and Salt.

On the base of this report merchants along the Osage petitioned the Missouri General Assembly and the U.S. Congress for development of the river, saying that “prosperity and development of south central and the southwestern regions of Missouri depended on it.”

No, in 1841, the state of Missouri had received from the federal government a half million acres of land; proceeds from the sale of the land was to go into internal improvements. The revenue was distributed equally among several counties, and the citizens of some immediately demanded this money be used in the development of Missouri’s rivers.

On February 15, 1847, the Osage River Association was formed and incorporated, and the following year a petition was made to the Miller County Court requesting that the county’s share of the land sales be put into Osage River improvements. The association had divided the river into five districts, with Tuscumbia to the mouth being the first. The second was from Erie, county seat of Camden County, to Tuscumbia.

While Miller County contributed considerable money toward the improvements only a few counties joined the association and so destroyed its effectiveness. However, the channel was much improved. There was snagging and low dams were built with timber and rock at an angle to back water up over the shoals. Some $50,000 was spent.

Captain Joseph W. McClurg, who was to become a famous Missouri statesman and merchant helped with his steamboat Emma, which was used to pull snags and tow rock barges to the cross dams erected below the shoals.

The association continued to function after the Civil War and had its largest convention on March 18, 1886, at Jefferson City, Mo. The steamer Frederick carried the Tuscumbia delegation to Jefferson City in eight hours, so averaging 10 miles an hour. J.B. Harrison, Tuscumbia, was a member of the board of directors of the association.

Because of strong requests by the citizenry for action, the U.S. Engineers’ Western Rivers Improvements office in St. Louis in 1870 instructed D. Fitzgerald to do a survey of the Osage with a view toward improvements. This was for a three foot channel He said that $200,000 was needed for the work between the mouth of the Missouri and Roscoe, Mile 238, was well worth it to open up the area for dependable navigation year round, and in the River and Harbor Act of 1877 Congress approved this funding.

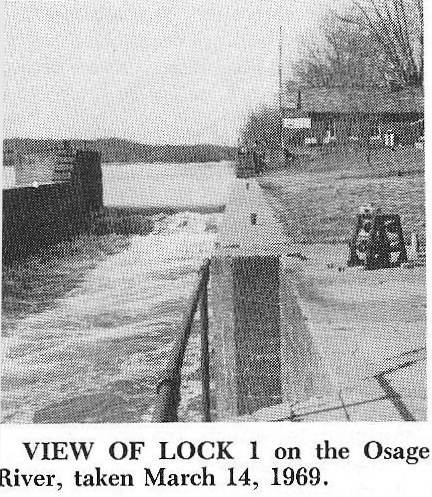

However, it soon became evident that this three foot channel could not be maintained only through snagging, dredging and wing dams. In 1890 Congress approved a lock and dam near the mouth. It was completed in 1906 but the dam soon failed and was not totally repaired until 1914. The structure was nine feet high and the lock was 220 by 40 feet.

The head of navigation was moved back twice as it became apparent that a three foot channel above Warsaw, Mo., was impossible because of the many shoals and rocks; in 1902 the head was moved back to Mile 185 and in 1904 to Mile 171 near Warsaw. The lock and dam did help Osage navigation and while Missouri River traffic declined the Osage remained an economical highway for rafts, railroad ties and produce.

However, Osage traffic was to end soon, through the competition of trucks on newly built roads, and finally the completion of the huge power dam by the Union Electric Company at Bagnell, Mo. about 80 miles above the mouth of the Osage. The Missouri River Division received official orders to close the Osage Lock and Dam down on June 15, 1951, and it was done on September 24. Thus, commercial navigation on the Osage ended. The lock and dam are still to be seen by those who might be interested (photo 19).

19 Lock on Osage River

Today, in addition to the huge Lake of the Ozarks that is supplied by Osage River water, the new Harry S. Truman reservoir is coming on line above Warsaw.

Our thanks to the Kansas City Engineer District,in particular to Bob McBee and George F. Hanley III in the Public Affairs Office, for their help in rounding up pictures and information on the Osage River Lock and Dam.

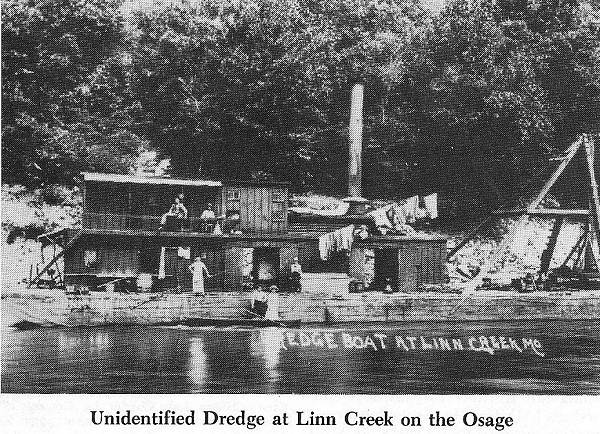

Regarding the dredge, we can’t find anything. The markings appear to read USN 1411 which doesn’t make much sense…unless this is a private dredge somebody bought from the Navy. Maybe somebody at Linn Creek knows the story (photo 20).

20 Dredge at Linn Creek

We have a letter from Captain Herb Hostmann, now of Hardy, Arkansas, who tells us that his grandfather Horstmann was a German sailor who sailed to new Orleans and from there took a steamboat to St. Louis There on the riverfront in a restaurant he met his wife.

“Nothing definite is known about their life but we supposed that they caught a steamboat and went to Linn Creek, for that is where he died. He fell off a horse and broke his neck. With this union they had two sons, one my father. His widow remarried a real nice old fellow and they live in Washington, Mo. I knew my grandmother very well, but by then she was rather old and not talkative. I was born in Washington and lived there until 1913 when I moved to Alton. My father died when I was five. My father’s brother lived in St. Louis; I knew him well but just didn’t talk about such things.”

This week while we are discussing steamboats I think it appropriate to remind readers that if you haven’t seen the Arabia steamboat exhibit in Kansas City you are really missing something interesting. Here is its website, address and phone number:

http://www.1856.com/

Arabia Steamboat Museum

400 Grand Blvd.

Kansas City, MO 64106

816-471-1856

The steamboat sank in 1856 and became completely covered with mud until it was excavated and recovered in 1989. What is really amazing beside the effort of recovery of the ship is the successful manner in which all the goods and ware were preserved. After cleaning they were presented in the museum looking good as new. The story of that effort, which is fascinating, is copied here taken from the Wikipedia website:

Early history

The Arabia was built in 1853 on the banks of the Monongahela River in Brownsville, Pennsylvania. Its paddlewheels were 28 feet (8.5 m) across, and its steam boilers consumed approximately thirty cords of wood per day. The boat averaged five miles (8 km) an hour going upstream. The boat traveled the Ohio and Mississippi rivers before it was bought by Captain John Shaw, who operated the boat on the Missouri River. Her first trip was to carry 109 soldiers from Fort Leavenworth to Fort Pierre, which was located up river in South Dakota. The boat then traveled up the Yellowstone River, adding an additional 700 miles (1,100 km) to the trip. In all, the trip took nearly three months to complete.

In spring of 1856, the boat was sold to Captain William Terrill and William Boyd, and it made fourteen trips up and down the Missouri during their ownership. In March, while heading up river, the boat collided with an obstacle and nearly sank. Repairs were made in nearby Portland. A few weeks later the boat blew a cylinder head and had to be repaired again. The rest of the season was uneventful for the boat until September 5.

Sinking

On September 5, 1856, the Arabia set out for a routine trip. At Quindaro Bend, near the town of Parkville, Missouri, the boat hit a submerged walnut tree snag. The snag ripped open the hull, which rapidly filled with water. The upper decks of the boat stayed above water, and the only casualty was a mule that was tied to sawmill equipment and forgotten. The boat sank so rapidly into the mud that by the next morning, only the smokestacks and pilot house remained visible. Within a few days, these traces of the boat were also swept away. Numerous salvage attempts failed, and eventually the boat was completely covered by water. Over time, the river shifted a half a mile to the east. The site of the sinking is in present-day Kansas City, Kansas, although, as described below, many of the remnants have been removed to a museum in Kansas City, Missouri.

Rediscovery and Excavation

In the 1860s, Elisha Sortor purchased the property where the boat lay. Over the years, legends were passed through the family that the boat was located somewhere under the land. In the surrounding town, stories were also told of the steamboat, but the exact location of the boat was lost over time.

In 1987, Bob Hawley and his sons, Greg and David, set out to find the boat. The Hawleys used old maps and a proton magnetometer to figure out the probable location, and finally discovered the Arabia half a mile from the river and under 45 feet (14 m) of silt and topsoil.

The owners of the farm gave permission for excavation, with the condition that the work be completed before the spring planting. The Hawleys, along with family friends Jerry Mackey and David Luttrell, set out to excavate the boat during the winter months while the water table was at its lowest point. They performed a series of drilling tests to determine the exact location of the hull, then marked the perimeter with powdered chalk. Heavy equipment, including a 100-ton crane, was brought in by both river and road transport during the summer and fall. 20 irrigation pumps were installed around the site to lower the water level and to keep the site from flooding. The 65-foot-deep (20 m) wells removed 20,000 US gallons (76,000 l) per minute from the ground. On November 26, 1988, the boat was exposed. Four days later, artifacts from the boat began to appear, beginning with a Goodyear rubber overshoe. On December 5, a wooden crate filled with elegant china was unearthed. The mud was such an effective preserver that the yellow packing straw was still visible. Thousands of artifacts were recovered intact, including jars of preserved food that are still edible. The artifacts that were recovered are housed in the Steamboat Arabia Museum.

On February 11, 1989, work ceased at the site, and the pumps were turned off.

Today

The site where the boat sank is an unassuming field about half a mile from the river. After the pumps were turned off, the site was filled back in so that it would not be a hazard to humans. The area is believed to be haunted by "Patchy," a local drifter who died nearby under mysterious circumstances.

That’s all for this week.

Joe Pryor

Previous article links are in a dropdown menu at the top of all of the pages.

|