|

Monday, January 30, 2012

Progress Notes

Raymond Hader, who was born and raised in north Miller County, now living in Jefferson City, came by the museum recently to share with me some information he had regarding the story of one of our state’s most infamous mass murders, that of the Miller County Carnie Parsons family, to whom Raymond is related (photo 01).

01 Raymond Hader

Carnie’s wife, Minnie Strange Parsons, was a first cousin to Raymond’s grandfather, Fred Hader. The Parsons and the Haders at that time lived near each other in the Bagnell area of Miller County. The Parsons family had moved to Texas County in the early 1900’s but after a few years decided to move back to Miller County at which time the murder occurred. The story of the family’s murder was so infamous that it made the headlines of major newspapers across the country. The most accurate and complete account of the mass murder is found in one of the “Bittersweet” publications. The author of the article does not give the background of the Miller County Parsons’ family as I did above, but does give a fairly complete and detailed account of the facts related to the murder itself and the trial later of the mentally retarded murderer, Jodie Hamilton:

Volume V, No. 3, Spring 1978

HANGED BY THE NECK UNTIL DEAD... DEAD... DEAD...

Condensed from Dying From Home And Lost

by Michael Duff and Barry Forman.

Drawings by Gala Morrow

If you ask people around these parts about Jodie's father James B. H. Hamilton, they'll tell you there was something "peculiar" about the man. He was a tall, lean Christian preacher who carried a Bible with him even while feeding cattle. For him there was no distinction between literal and symbolic truth. The Bible was the Truth, with its redemption, salvation and grace. The Word stood there plain and simple in the Good Book.

Jim was strict with his kids, refusing to let them go drinking and square-dancing. Even when they sang, it had to be hymns. When John Platter came by to sing with them one night and shuffled his feet, Jim caught him up right smart, "No, John, don't have no dancin' here."

His family toed the line, by God, and people talked how the preacher, loving his kids like that, used to kick them around if they strayed from the chosen path. He had a temper mean as a double-geared saw engine and didn't think twice about filling his cattle full of buckshot when a dark mood came upon him, which was often. Some folks, who didn't take to him, claimed he tortured those cattle for amusement and out of a mean streak.

Jim Hamilton married Mary Taylor who bore him four children, Joseph Hamilton was the fourth child. Some called him Jodie and some called him Jodia. He was a slight boy, 5 feet ten inches. Quiet, polite, dignified, Jodie always dressed neatly and, like the rest of his brothers and sisters, very much feared his father and respected the God his father preached. But from the outset, bad luck seemed to dog the boy. His mother died when he was five years old. At seven, a kick in the head by an old gray mule left a scar over his left eye for the rest of his life. Some years later, he was out feeding and currying mules again when one let fly, kicking Jodie in the breast and knocking him unconscious. And then, at twelve, a tree fell on him and almost broke the boy's neck.

Jodie was an ordinary enough fellow to those who knew him, just another mountaineer farm boy who could handle a horse and a team. They all thought well of Jodie, despite his occasional bursts of temper, like the time he fought John Platter and beat him so bad John was three days in bed recovering. Seems that Jodie, probably because of that mule-kick in the head, had these spells of uncontrollable violence when he didn't know what he was doing, and at these times, his anger knew no bounds.

Jim Hamilton had remarried and the family left the Ozarks for Plains, Kansas, in 1902 taking Jodie and the other children with them. Jodie stayed there working with his father, but always wanted to return to Texas County, Missouri. None of his family wanted him to go but Jodie returned to Texas County in August, 1906, and went to work as a hand for Carney Parsons, a share-cropper.

Carney Parsons was a strong man, thirty-five years old and well-liked by his neighbors. The Parsons had only been in Texas County two or three years at the time Jodie went to work on their farm. The two men seemed to get along all right at first. Jodie was religious, hard working and liked children. He used to take candy and chewing gum over to the neighbor kids and give them horseback rides. He would play with Parsons' three young boys as well.

Jodie knew Mae Thompson before his family left for Kansas. But he first started courting her when he came back. She was about sixteen years old and very pretty. He was twenty years old. Before long they became engaged to be married. The money he made working for Parsons was to go for a farm where they could settle down and raise a family. Jodie really loved Mae and there was probably nothing in some people's talk that the young man had his eye on Carney Parsons' wife, Minnie.

Trouble grew up between Parsons and Hamilton. Probably it was because Parsons knew that Jodie had stolen a horse. That is, he had found a horse with a handsome saddle and not bothered to look for its owner. This might have been one reason Parsons and his wife opposed Hamilton's marriage and why, according to Jodie, Parsons had been telling lies about him to Mae Thompson.

Then Parsons' wife Minnie grew pregnant and wanted to return to her home. So Parsons sold his share of the corn crop to Hamilton and prepared to move his family back to Miller County where he had put money down on a farm.

On Friday, October 12, 1906, Parsons asked Jodie if he would trade the stolen saddle for Parsons' single barreled breach loading shotgun and twenty-five dollars. Hamilton refused. Parsons pressured the young man, saying he knew damn well it was stolen and it wouldn't sit well with Sheriff Wood to know who stole it. Hamilton said he would trade the saddle for the shotgun and thirty-five dollars, but Parsons, bargaining with threats, got the price back down to twenty-five. Saddle, gun and money changed hands. Parsons put his wife and three little boys on the wagon and started out about 11:30 in the morning. Without a goodbye Jodie watched them depart.

But, thinking about the trade, Jodie began to get more and more angry, certain he had been cheated. After awhile, he picked up the gun and took off after Parsons on foot. He knew the road and chose an overland short cut and caught up with the Parsons about noon.

Jodie later explained, "It seemed like I was all tore up in my mind. He had told such lies about me and got me to go ahead and make a trade after I had decided I didn't want to. It seemed like it all come on me at once." He and Parsons had words. Then Parsons whipped up the team and continued on down the road. Jodie caught up with them again. "I had no intention of killing him," Jodie said. "But I was determined he should fix things right or we would have trouble."

By the time Jodie reached the Parsons the second time, his anger was uncontrollable. The two men had a powerful quarrel, terrifying Minnie and the three little boys. Seeing that Hamilton was losing his temper, Parsons pulled a knife from his pocket. Jodie raised up the shotgun and fired at the farmer while he was still seated in the wagon and hit him in the right leg just above the knee. With the shot the gun broke into three pieces. Before Parsons could recover, Jodie picked up the gun barrel and struck him on the head. Minnie tried to wrest the barrel from Hamilton, who struck her with it.

She fell to the ground. The children were crying. The blood was beating in his temples so Jodie couldn't think what he was doing, but he knew he had to silence the children. He hit first Jesse, then Frankie on the head with the barrel. Then with Parsons' own knife, he cut their throats. But Minnie wasn't dead and was on the ground at Hamilton's feet, clutching at his leg. He took her, threw an old blanket from the wagon over her head, and beat her to death with a double-bit ax. The year-old infant lay crying in the wagon. Jodie hesitated a moment before he lifted the gun barrel again and ended the poor child's life. It was done. Jodie Hamilton had killed five people.

Jodie rifled Parsons' pockets, taking a razor, spectacles, twenty-five dollars and a gold watch. Then he put Minnie Parsons on the wagon. He drove the wagon into some cover by the side of the road. He unhitched the team and saddled one of the mules with the saddle he had traded Parsons that morning.

That evening Mae Thompson prepared for the arrival of her fiancé. Mae's brother greeted Jodie as he rode up to the house. He chatted amiably with the family for a while before they left for a revival with Jodie, Mae and Mae's deaf and dumb brother all together. Mae was riding Carney Parsons' mule, and Jodie leading it. The Thompsons said they'd follow shortly. They came to a fork in the road, and Jodie suggested they take the old road through the woods instead of the shorter main road. Mae said, "No, I don't want to. Something tells me not to." So they took the main road and arrived at the revival without incident. Days later, after Jodie had been apprehended, he admitted that he had intended to kill Mae Thompson that night and would surely have done so, had she agreed to take the road through the forest, because he'd rather she be dead than know the truth about what he did that afternoon and not love him anymore.

When he was alone, Jodie borrowed a horse. He reached Parsons' wagon where he had hidden it the preceding afternoon and harnessed the horse and the mule. It was about 1:30 in the dead of night. But he got stalled and couldn't get the horse to pull. Just before daybreak he went to borrow another mule.

Jodie took that mule and hitched it up with the other one to Parsons' wagon and started to drive down to the river. He arrived at the east bank of the river just about sun-up. He dragged the bodies out of the wagon and, one by one, pushed them over the dirt bank into the water. When this work was finished, he drove the wagon off into a nearby hollow and left it there. Then he took back the borrowed mule. He returned to the wagon, saddled up Parsons’ mule again, and returned the borrowed horse.

That same night, while Jodie Hamilton was at the revival meeting with Mae Thompson, three men camped on the west side of the Big Piney River for a fishing trip. Early Saturday morning, one was fishing when something caught his eye over by a flat rock in midstream. At first he thought it was a rag doll with flowing blonde locks, but closer inspection proved otherwise. He shouted to the other two men, who came running. The bodies of two little boys, Jesse and Edward Parsons, were pulled onto the west bank. Saturday evening Jodie met the Thompson family about five o'clock. They were planning to attend church together. When Jodie entered the house, Mr. Thompson asked him if he had heard about the bodies of the two children found in the Big Piney. Jodie replied, no, he hadn't.

Later Jodie described this encounter, "They told me that someone had found some children in the river, and I knew then that they would find out it was me that killed them. When I heard them talking about it, it seemed like I couldn't stand it and I got up and pulled out." Making the excuse he had to go to Licking on business, Jodie hastily departed from their home and went about three-quarters of a mile toward Licking. Then he went to Houston about eight o'clock that evening and stabled his mule at the livery barn, where he said that he had been working in Raymondville and wanted to hire a horse to go to Cabool. Jodie's idea was to catch a train from Cabool and go to Kansas to kill his father.

Ex-sheriff James W. Cantrell and a Deputy Sheriff came to the livery barn, where they heard Hamilton had been seen. Jim Cantrell asked to see the mule Jodie left behind and identified it as having belonged to Carney Parsons. Cantrell telephoned ahead to a general store along the route to Cabool and asked if Hamilton could be detained until he could arrive. When Jodie got to the general store, the owner invited him in for a cup of coffee. Jodie declined, saying he was in a hurry, but he finally was persuaded to come inside for just a minute. Cantrell and the deputy rode up shortly afterward and burst into the room, their guns pointed at the young man. Cantrell said, "Jodie, don't move now, it's all over." It was ten o'clock at night. Immediately the boy broke down and confessed his crime. They searched his pockets and found Parsons' spectacles, razor and twenty-two dollars. Cantrell handcuffed Hamilton securely and then brought him back to Houston and put him in jail. All told, he was arrested within thirty-six hours of having committed the murders.

Jodie told authorities where he had thrown his victims into the river, and Sunday, just after lunch, searchers found the other three bodies.

That Sunday morning, after Hamilton had been arrested, a mob, disorganized and without a leader, collected in front of the Houston jail. Men carried guns in plain sight and tension was high. Sheriff Wood appointed twenty special deputies armed with Winchester rifles and posted them around the jail house to protect the prisoner's life. It was clear to Wood that Hamilton, for his own safety, would have to be removed far from Houston as soon as possible.

Terrified of mob violence, Jodie raved in his cell like a madman. First he attempted suicide with a knitting needle, stabbing himself once in the neck and once in the chest above the heart. It was taken from him in time, and no one ever knew where it came from in the first place. Then he asked a deputy if a man could kill himself by butting his brains out and began beating his head against the cell wall. Hamilton was caught and bound, suffering nothing but minor scalp wounds. The young man was frightened and panic-stricken, but without a word of regret.

At six o'clock Sunday night, just after dark, Sheriff Wood and his deputies conveyed Hamilton by carriage to Cabool where they got on the train to Springfield. All the way Hamilton raved. In Springfield they took Hamilton off the railway car away from the platform, so that he wouldn't be seen. There was a curtained carriage waiting for him in the rear of the railroad yard, and by a circuitous route Hamilton was taken to the Springfield jail. But the depot-master and engine herder saw Sheriff Wood and the prisoner leave the train, and news of Hamilton's presence spread quickly.

Monday morning a closed wagon with guards drew up to the train depot at twenty minutes after noon. This was a ploy of the sheriff to convince people that Hamilton had been taken to Greenfield, in Dade County, and a story to that effect ran in the Springfield Leader. Hamilton was in neither the wagon nor the train, but still back in the jail house.

By six o'clock Sheriff Wood was at the Springfield train station saying that he was returning to Houston, via Cabool, on the six-fifty train. He began to talk freely to by-standers to attract attention. Meanwhile another officer took Hamilton, who was handcuffed and shackled, in a closed carriage to the depot, arriving five minutes after Sheriff Wood. Hamilton was hustled unseen onto a day coach to Carthage in Jasper County, Missouri. The ruse worked perfectly and just in time. About nine o'clock that night fifty armed men arrived in Springfield from Houston, looking for the prisoner. No one doubted when they would have done, had they found Hamilton. Three of their leaders went to inspect the Springfield jail. Satisfied of Hamilton's absence, they returned to Houston.

Carthage is about four hours by train from Springfield. Hamilton, who had been terrified out of all reason by the Springfield mob, calmed down during the trip. He told how his own mother had died while he was still a boy and said a disagreement with his step-mother caused him to leave Kansas. That kick from the gray mule caused his head to pain unbearably at times he said, so that he had little or no recollection of his action. Mae Thompson was the only girl he had ever loved. His fear was that she would dismiss him on account of what he'd done, and if she did throw him over, that this would be the worst punishment he could receive for his crime. He hoped she would still give him some recognition, though he did not expect it. By ten-thirty Monday night, Hamilton was safely behind bars in the Carthage jail, and only a handful of lawmen had any idea of his whereabouts. He seemed in control of himself for the first time.

On Monday Night, October 21st, Hamilton was brought back to Houston from Carthage by Sheriff Wood. Wednesday morning the preliminary hearing was held. Jim Cantrell, to whom Hamilton had confessed the murder, recounted the confession and other matters relating to the crime which had come under his observation. On the basis of this testimony alone, the judge committed Hamilton to jail to await the Circuit Court on charge of murder.

Jodie Hamilton came before the circuit Court judge and entered a plea of guilty to murder Monday morning, November 12th. In Missouri the death sentence cannot be passed on a man who confesses without trial. And so the judge, reluctant to pass sentence himself and accept responsibility, impaneled a jury of twelve men.

The prosecuting attorney asked Hamilton if he acknowledge being guilty. Jodie replied that he did, saying, "Well, the circumstance is that I am up here before you and I have committed a crime. Committed the murder and it can never be called back. It was brought on in my angered mind. I just got my mind started and I couldn't stop it. It seemed like when I got into it with the man, I was plumb wild and I am up here today with the crime of murdering the whole family." One of the jurors asked him, "Had you thought of it?" And Jodie replied, "No, sir, I never thought anything about it. About the first I thought anything about hurting the old man was just when it come on my mind all at once. It was after I overtook them. It seemed like I was all tore up in my mind ...." Jodie wound up his confession to the jury by saying he was guilty and willing to take the consequences.

The attorney for the defense called but a single witness to the stand, Jodie's brother, who was questioned about the kick Jodie had suffered from a mule when he was a boy. A doctor was asked to examine Jodie's head, to see whether that kick caused a pressure on the brain which might have resulted in temporary insanity. His opinion held that the kick had in no way affected Hamilton's brain.

With this the jury retired and after less than an hour of consultation, returned a guilty verdict. Hamilton was asked if he had anything to say why the death sentence should not be passed on him. He replied, "I am sorry I committed the crime, but am ready to die." The judge pronounced the sentence, "Jodie Hamilton, I sentence you to be hanged by the neck until you are dead, dead, dead, and may God have mercy on your soul."

The time of execution was set for Friday, December 21st, 1906, fourteen days after his twenty-first birthday.

It should not be thought that people were totally without sympathy for Jodie. Many came to visit him in his cell, people who did not know him and simply wanted to see for themselves whether the boy appeared sane or insane, and others who did, acquaintances, neighbors and schoolmates. Jim Hamilton traveled to Jefferson City, petitioning the governor for more time for his son, who, he claimed was insane. But on the 15th day of December, the governor declined to stay the execution. Jodie's last hope was shattered.

After that, the boy seemed to take an impassioned interest in the details of his execution to come. On request, Sheriff Wood removed Jodie from the jail and permitted him to inspect the gallows on which he would be hanged. He sprang the trap and examined every part without the least sign of fear or emotion, almost as though the whole thing were a serious joke, and told Sheriff Wood that he thought the gallows was a good job and would certainly do the work assigned to it. But could the sides of the trap be padded, he wondered, so that his body would not be damaged in falling through?

It was cold and cloudy Friday morning the 21st of December, and by daybreak young men had already climbed the trees behind the court house to wait, so they could have a good view of the hanging. Houston was crowded with over 600 people from the surrounding countryside and nearby towns. A few had even come from out of state to witness the first, and the last, legal hanging ever to take place in Texas County. Many of these people had camped Thursday night about the town. Mae Thompson had come with her family.

No specific time for the hanging had been set, and the crowd stood about in the cold talking and drinking, while various preparations were made. The rope noose hung in readiness. It had been sent to Sheriff Wood from Aurora three days earlier, and was the same one that had been used to hang a Negro named Ed Bateman the previous August.

At a quarter after ten, the gate of the enclosure was opened. In a few minutes Sheriff Aaron Wood came out, looking like a ghost of himself. People knew he had been drinking heavily--the only way he could bring himself to hang a boy he felt was insane.

Jodie had slept soundly that night. He seemed cheerful upon awaking, shaved, dressed in his best clothes and ate a hearty breakfast. At 10:42 he came through the jail door for the last time, supported by deputies who took the prisoner to the foot of the thirteen stairs leading to the platform where the gallows stood. Jodie climbed the scaffold without a tremor and took his station between two preachers. The crowd began singing "Jesus, Lover of My Soul" and Jodie joined in, which caused a wave of sympathy for him in the people.

Sheriff Wood asked Jodie if he wanted to talk. The young man indicated he did, and stepped up on a box, so those outside the stockade could see him. "I guess you all know what I am here for. I don't blame the judge or any of the officers. I owned up to it all like a gentleman. I stuck to the truth all the way through. Of course, the officers have to do their duty, and we all have to abide by the law. I cannot think hard of the officers. I would like to say while there are so many young men here standing before me today--they ought to take warning before it is too late. I have one song that I wish to sing and I will try to sing it:

"Companions, draw nigh, they say I

must die,

Early the summons has come from

on high;

The way is so dark and yet I must go,

O, that such sorrow you never may know.

"Ah, can you not bow and pray with

me now?

Sad the regret, we have never

learned how

To come before Him, who only can save,

Leading in triumph thro' death and

the grave.

"(Chorus) Only a prayer, only a tear,

O, if sister and mother were here;

Only a song, 'twill comfort and cheer,

Only a word from that Book so dear."

Sheriff Wood then asked "Is that all?" Jodie continued, saying, "I don't want to make much of a talk. Of course there is one thing-let all the young people here today standing around seeing this going on, they ought to take warning now to help each other to trust in the Lord, to help each other to talk to their friends and trust in the Lord. He will help you if you will listen. If you follow the devil's way he will lead you wrong every day of the world. I have been a poor sinner myself. I have been trying to trust in the Lord, to get forgiveness for all my sins, and if we will only trust in Him, He will surely help us each and every one. And, now as you all see how it is with me, that I am led astray and drawn into trouble unexpectedly, and now you see how I must go today. Now my life is taken away, but I hope and pray to meet God in peace and hope to meet father, mother, brothers, sisters and friends, I say friends, because I hope everybody here is my friend. All young men should treat their parents with respect and listen to their parents. Their parents will always try to teach them right, and if they will listen to them, and trust in the Lord, He will have mercy on them. I don't know as I can say much more."

When Jodie finished, the crowd was silent. A few women had begun to cry. Then a church elder spoke up, "Just one thing more before prayer. I would like to say: People, be obedient to the laws of the civil authorities; be obedient to the laws of nature; be obedient to the Divine Laws of God. If we do not, penalties are attached to these three sets of laws. --Our Father, who art in Heaven, hallowed be thy great and holy name, we come before Thee this morning. We know that the one standing before us has disobeyed the law of civil power, and kind Heavenly Father, we find according to the law of civil power for this disobedience, that natural death must soon come. Now, kind Heavenly Father, we ask Thee to be with him and those present, that they may lead quiet, peaceable and obedient lives. Be with this one, kind Heavenly Father, if in harmony with thy Divine will; be with him, O God, in death, that he may receive eternal life after natural death. Kind Heavenly Father, for this one we come this morning, presenting ourselves in Christ's holy name."

Then Jodie Hamilton said, "Now, dear friends, as my sentence has come, I hope to meet all you friends standing around here today in a better world. Try to be faithful and meet God in peace, and hope to meet in the better world."

The sheriff of Shannon County beckoned to Jodie to take his position on the trap door. A sheriff from another county and a deputy bound Jodie's arms and legs, while Jodie uttered a prayer, "Lord, have mercy on my poor sinning soul. Lord have mercy on me and on my soul! These my last few words to say." Those present on the scaffold took Jodie by the hand, bound as it was, and bade him goodbye. He nodded calm and pleasant like he was going on a journey somewhere far away. The sheriff slipped a black cap over the young man's head. Aaron Wood adjusted the noose about his neck, tight. In a deep, guttural tone, Jodie cried out through the black mask, "Lord, have mercy on me, on my soul." Aaron Wood reached for the lever, saying, "Jodie, God have mercy on your soul!"

With those words, the trap was sprung. The time was 11:02. Then a terrible thing happened. The knot in the end of the rope came out. The noose slipped from Hamilton's neck and he fell backward, stunned, injured, but still conscious. The crowd let out a gasp of disbelief and fright. Mae Thompson fainted in her father's arms. The sheriff quickly went to work tying another knot. Hamilton lay on the ground, repeating over and over again, "Lord, Lord, have mercy on my soul." The people wondered whether that rope, tested by four men, had been tampered with. An old midwife, standing outside the stockade, yelled to Jodie, "That one's for the baby!"

The officers picked Hamilton up off the ground and started carrying him back up the thirteen steps to the gallows. He was again placed on the trap, which had been re-set. Sheriff Wood put the noose about his neck, with Hamilton pleading, "Don't draw it so tight--it is choking me." At 11:04, the trap was sprung a second time. The knot held. Jodie Hamilton's soul plunged into eternity. His toes just barely touched the ground, since the second knot had taken less rope than the first, but the fall broke the boy's neck. At 11:17, the attending physicians pronounced him dead. Three minutes later the body was cut down and placed in the waiting coffin and was carried to the courtyard and placed on display where that day all who wished could take their last look at what remained of Jodie Hamilton.

Saturday morning, as Jodie and his father, who was not in attendance at the hanging, had requested, the coffin was taken to Allen Cemetery, near Raymondville, hauled by the mule team that had belonged to Carney Parsons. Twice the coffin was lowered into the grave. But the grave was too short. One man climbed down into the grave and jumped on the coffin, but it would not go in. Rather than widening the grave, someone knocked in the end of the coffin with a pick until the box fit the hole. Before a crowd of onlookers, the body of Jodie Hamilton was laid to rest in an unmarked grave beside his dead mother.

That was how it happened, as near as anyone can tell today, seventy-two years later. The hangman's rope was cut up and sold for souvenirs for twenty-five cents a piece, and postcards were printed with three photographs of the hanging and one of the dead bodies of the Parsons family. Aaron Wood was elected sheriff another term, and he served until 1908, just about the time Mae Thompson married.

People always wondered about that rope with a noose at either end, how it had been tested by officials beforehand without any deficiency being found, and how it would seem it would have had to be meddled with to slip like that.

Folks admired Jodie's nerve those last few days. They thought he would collapse on the gallows, instead of standing there calm and more composed than most of the people watching him die, smiling, singing, acknowledging a divine power, and casting his eyes upward at the heavens with true penitence. His story is still told around these parts as a legend--the murder, the church-going, the capture, and the hanging that December morning in 1906, four days before Christmas.

Copyright © 1981 BITTERSWEET, INC.

Raymond Hader told me that in those days, it was common that photographs of victims as well as murderers would be sold by hawkers and vendors. Raymond has some of the photos sold after the hanging of Jodie Hamilton. The first and most popular photo sold was that of the Parsons family laid out on a bed, presumably at their home near Houston.

Here is a photo of the deceased Parsons family which is in the possession of Bill and Betty Roark of Olean (photo 03).

03 Parsons Family Murders

Betty told me the photo was one of those originally sold by local vendors during the time of the trial of Jodie Hamilton.

In modern times some may find it almost surreal that a tragedy so horrible had elements of commercialism and mercenary motivation so unabashedly demonstrated. But times were different then. I have commented in previous Progress Notes that I as a child going to the Tuscumbia picnic in the 1940’s remember tent shows where people with severe deformities were paraded before us, deformed fetuses were displayed in formaldehyde filled jars, and brutal fist fights were staged between carnival employees and locals hoping to win a cash prize.

The Parsons family multi murder tragedy is one of several recorded involving Miller County citizens. Others can be reviewed at these websites:

Five Killings by Captain Thomas Babcoke

Seven Killed at Curtman Island by Crabtree

Five Killings in Iberia which were Civil War related

Sandra Belle Wilson Murder

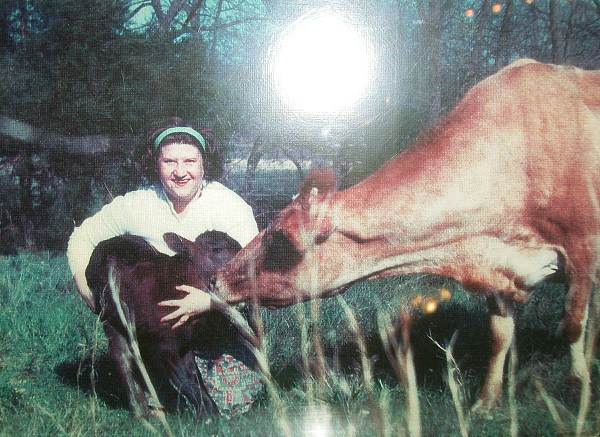

On a much lighter note I’ll change the subject to highlight one of our very interesting displays at the museum donated to us by friends of Louise Katherine Nixdorf of Ulman. Over quite a number of years Louise enjoyed the hobby of sewing together stuffed animal toys using common materials and fabrics. Here is a photo of Louise taken many years ago on her farm near Ulman (photo 05).

05 Louise Nixdorf

And here are photos of the stuffed animal toy display now on exhibit in the upper level of our new addition to the museum (photos 06, 07 and 08):

06 Stuffed Animals

07 Stuffed Animals

08 Stuffed Animals

Another photo is of Louise when she was a young girl (photo 09).

09 Louise Nixdorf as a Child

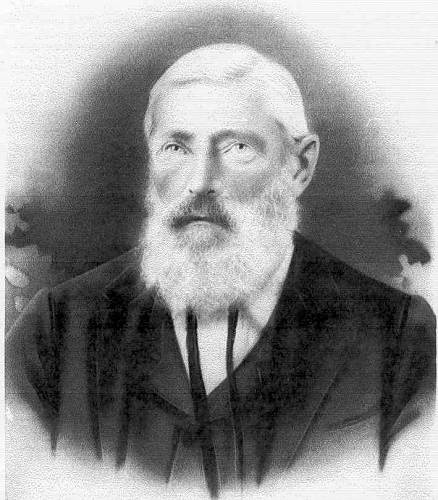

Louise passed away on January 31, 2004. She was born in Ulman on February 10, 1922, a daughter of Carroll and Josephine (Burks) Nixdorf. Carroll Nixdorf was a son of Anton Paul Nixdorf M.D, from whom all the Miller County Nixdorfs descended (photo 10).

10 Anton Paul Nixdorf M.D.

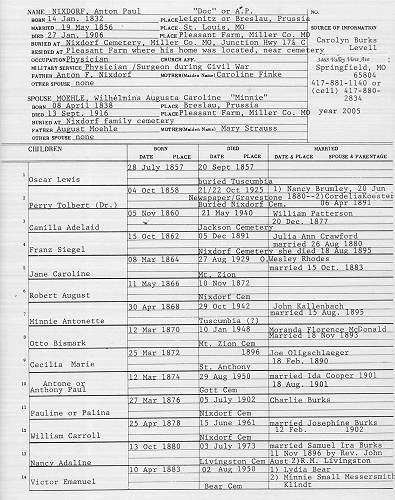

Here is a chart of Dr. Nixdorf’s descendents provided me by Carolyn Burks Levell of Springfield (photo 11):

11 Nixdorf Genealogy

Click image for larger view

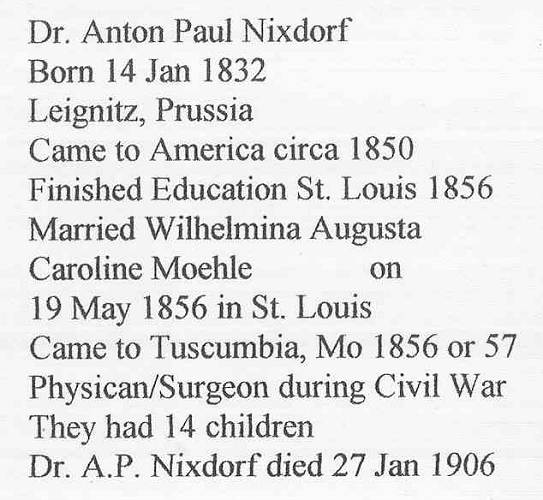

A short summary of Dr. Nixdorf’s biography is listed here (photo 12):

12 Anton P. Nixdorf Bio

You can read more about this very famous early Miller County physician at this previous Progress Notes.

Here is a photo of Louise with her sister Jesse Nixdorf and parents Carroll and Josie (Burks) Nixdorf (photo 13):

13 Josie, Carroll, Louise and Jesse Nixdorf

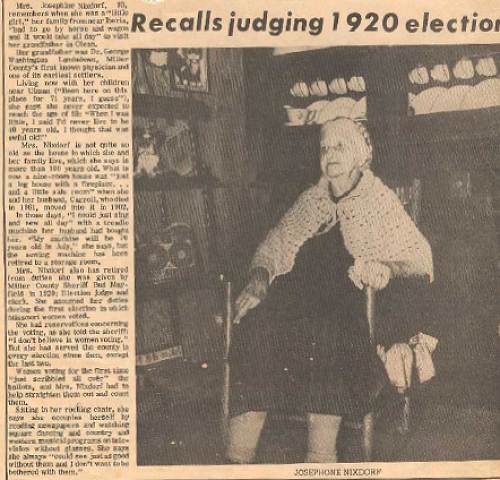

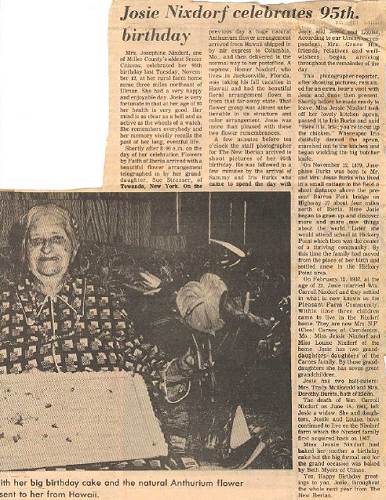

I found two very interesting Miller County Autogram Sentinel clippings from our files featuring Josie Nixdorf; one on the occasion of her 93rd birthday and the second on the occasion of her 95th birthday (photos 14 and 15).

14 Josephine Nixdorf 93rd Birthday

Click image to view article in PDF format

15 Josephine Nisdorf 95th Birthday

Click image to view article in PDF format

Louise and Jesse Nixdorf lived with their mother, Josie, in the home of their birthplace all their lives. Jessie was an eighth grade school teacher both at Tuscumbia and School of the Osage. She taught me when I was in the eighth grade at Tuscumbia and she taught my wife Judy (Steen) eighth grade when she was eighth grade teacher at the School of the Osage. Here is a photo of Jessie I copied from one of the School of the Osage annuals (photo 16).

16 Jesse Nixdorf

I will always remember “Miss Jesse” because if it were not for her, I may never have learned English grammar. She was an excellent teacher.

That’s all for this week.

Joe Pryor

Previous article links are in a dropdown menu at the top of all of the pages.

|