|

Monday, February 13, 2012

Progress Notes

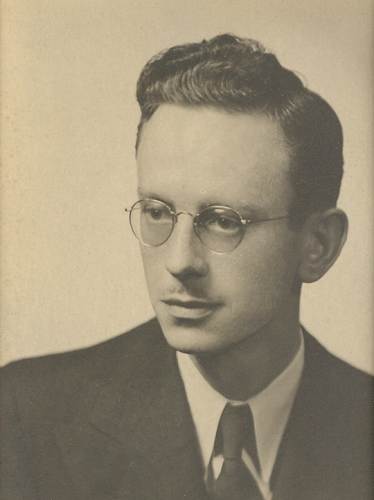

When I was a boy in the 1940’s my family made a weekly drive to Camdenton to visit my Aunt Lois Pryor Cunningham and her husband Lieutellus Cunningham (photos 01 and 02).

01 Lois Pryor Cunningham

02 Lieutellus Cunningham

Uncle Lou was born and raised in Bolivar but after finishing law school he moved to Camdenton where he served as prosecuting attorney in the late 1940’s. During those weekly drives one of the things I remember is how the Lake tourist industry was expanding by leaps and bounds every year! Some of us locals didn’t appreciate the business opportunities the lake offered as well as those did from outside the area who were charmed and enamored by the beauty of the Ozarks and the magnificent Lake formed by Bagnell Dam.

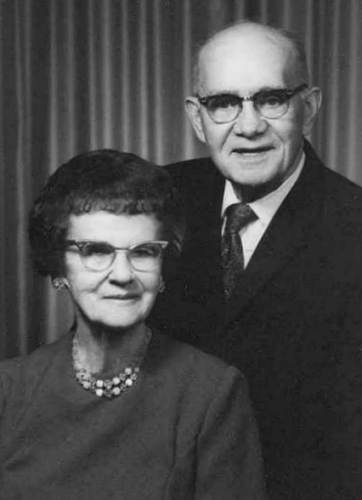

One of those who did recognize the opportunities here was my Uncle Bob Craven, originally from Granite City, Missouri, who had married my grandmother’s sister, Alma Abbett Craven (photo 03).

03 Bob and Alma Craven

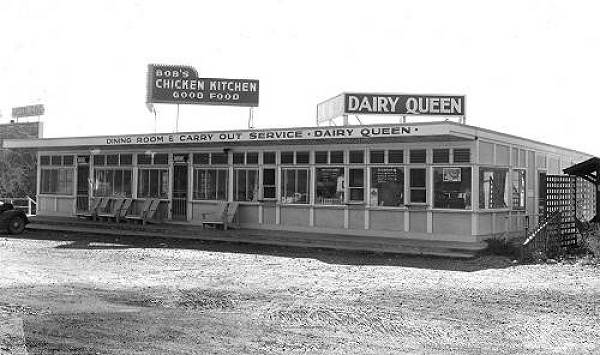

Aunt Alma had moved from here during the depression to Granite City in the 1920’s where she met and married Bob. After visiting this area Uncle Bob decided to leave his hamburger restaurant in Granite City to come here and establish a restaurant at Lake Ozark which he named the Chicken Kitchen Restaurant. For quite a few years Uncle Bob and Aunt Alma owned the restaurant which was located at the south side of the Lake Ozark strip very close to the Dam (photo 04).

04 Bob's Chicken Kitchen - Lake Ozark

One local person who recognized the opportunities for establishing a tourist oriented business at the Lake was Tuscumbia raised Lee Mace (photo 05).

05 Lee Mace Playing Bass Guitar

You can read about Lee and his very successful Ozark Opry show at these previous Progress Notes:

- July 21, 2008

- October 11, 2010

Lee’s shows on the road throughout the Midwest gave him ample opportunity to spread the news to his audiences about the many recreational opportunities at the Lake. Lee was a supporter of all the tourist industry related business’s at the lake because he felt that the more attractions available to visitors would increase the number of people who visited each year. Lee especially enjoyed spinning yarns and stories about his hill country roots down in the Ozarks where he was raised. He was so good at this that some times city newspapers sent their reporters out to review one of Lee’s shows whenever he was appearing in their area.

One of these newspaper articles appeared in the St. Louis Globe Democrat in 1964:

Ozark Music Man

Globe Democrat Sunday Magazine

May 17, 1964

Lee Mace and his hillbilly entertainers pack ‘em in all over Missouri and are a solid hit on TV

By SHIRLEY ALTOFF

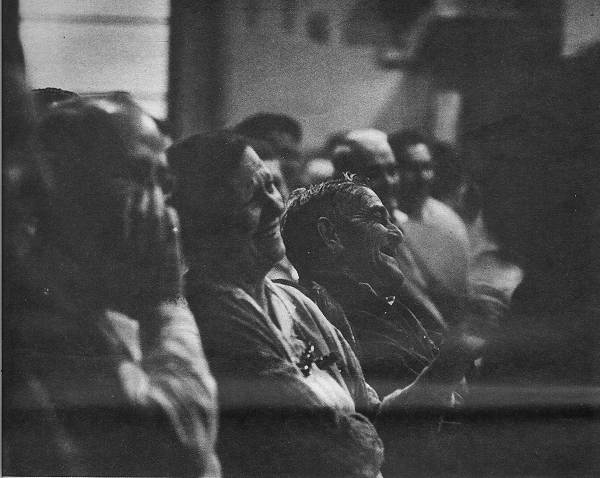

One evening not long ago, more than 600 persons crowded into a small school gymnasium in south central Missouri to watch a country music show. For two hours, members of the audience tapped their feet to jig steppin’ hoedown tunes and rousing old time gospels. They listened appreciatively to plaintive ballads whose notes and words had never seen a sheet of paper and clapped loudly at an occasional rural rock’n roll number thrown in for the young folks.

Throughout the evening they roared with laughter at homespun humor that wouldn’t offend the strictest fire and brimstone preacher.

What is so unusual about this?

Well, for one thing, the population of the town numbers only 25.

Then there’s the name of the town…”Success”

Success is the word that sums up country music man Lee Mace and his Ozark Opry. Mace and his outfit play before crowds of up to half a million people a year, as well as appearing in 50,000 or more Missouri homes each week on a half hour television show out of Jefferson City and Sedalia.

Their one night personal appearances are booked a year in advance and sponsors wait in line as long as three years for their turn to pay the tab for the TV show.

Furthermore, job offers continue to pour in the year ‘round.

Some 120,000 St. Louisans saw the Opry when it played the 1964 Midwest Sports Show here earlier this year. And during the summer, thousands of other city slickers pour into the Opry auditorium at Osage Beach at the Lake of the Ozarks for an evening of country music.

“Yep, I guess you might say we’re cuttin’ ‘er just about right” drawls Lee Mace, the Opry’s owner, manager, emcee and free wheeling bass fiddle player.

“For eight years, we never asked anybody for a job and now we turn down more work than we do.”

Lee, who is 36, has jet black hair and eyes, is thin almost to the point of gauntness. At six feet two, he weights from 135 to 165 pounds, “dependin’ on if we got the candle lit at both ends.” Despite his soft spoken, easy going manner, he is an intense man with boundless nervous energy.

And the Ozark Opry is more than a way to make a living for him; it is a way of life. Born on a small farm near Brumley, a village of about 80 people eight miles away from Osage Beach, Lee takes great pride in his country heritage.

“Folks don’t insult me by callin’ me a hillbilly. Honestly, I’m proud to be one. Money’s not the most important thing to these folks, but honesty, loyalty and friendship is.

“Any business that succeeds has to have goals. Just to open the doors to make money is no good,” he continues.

“Everywhere you looked years ago down in this part of the country there was just Ozarks. Now you can hardly see the Ozarks for all the other things around. I think we have somethin’ in this country worth preserving, and in our own way, that’s what we try to do. Most professional entertainers would laugh us off the stage. They’d say, ‘you couldn’t “pick” at Shady Grove.’ But we’re country people and we bring real country music to the public. A lot of the songs we do are authentic Ozarkian folk tunes. Some of them like ‘Marmaduke’s Hornpipe’, an old boy named Green Phillips sang to my Dad, and later Dad sang them to me.”

Lee’s father, by the way, is Lucian Mace, state representative from Miller County.

Note: Lucian served two times as state representative, once in 1940 and the second in 1962, each for two years.

The other goal of the Ozark Opry’s head man is to provide good, clean entertainment for the whole family. And to this end, Lee will not allow the group to play anywhere liquor is sold. While he doesn’t drink himself and he gave up smoking last year (after being a two to three pack a day man), he is no zealot about drinking.

“I just don’t think kids should be around when older people are drinking,” he explains.

A man who sticks to his principles, he recently turned down a $1000 offer from a St. Louis advertising agency for a one minute television commercial when he found out it was to be for a brewery.

While Joyce, his wife of 13 years, “built” a pot of coffee in their attractive ranch house just behind the Opry auditorium, Lee recalled how he got started in the entertainment business.

“Mom set out to make a fiddle player out of me when I was six. She liked songs like ‘Row, Row, Row Your Boat’; I liked tunes like ‘Ragtime Annie’.”

Later, he taught himself to play the guitar, bass fiddle and other string instruments. In addition, he learned the unique little jig step that sets Ozark square dancing apart from the western variety. And he and Joyce and some of their friend got quite a reputation as a square dancing group.

In 1948 when the director of the National Folk Festival in St. Louis wrote the Camdenton Chamber of Commerce asking for square dancers, Lee and his group were sent to participate in the festival. They made such a hit that the National Square Dancing Association asked them to perform at their convention in Kansas City. After that, Ted Mack invited them to dance on his television show. Following their TV appearance, they were booked at hotels and night spots that included Las Vegas, Reno and New Orleans.

“We were doin’ pretty well, but none of us wanted to go at it real professional and besides, we didn’t like livin’ out of suitcases,” Lee points out.

So when he got out of the Army in 1953, he and Joyce decided to put on a country talent show in a rented building right next to Bagnell Dam. They soon were packing people in.

Then Lee got the idea for a possible television show.

“I went to the Missouri Farmer’s Association and saw the advertising manager of the plant food division…that’s a fancy name for fertilizer. He came to see us perform, and said ‘this is it’ and bought the show for 13 weeks. I guess he believed we couldn’t only spread it, we could sell it. And we’ve been on TV ever since.”

In 1957 the Maces borrowed $30,000 and built the Ozark Opry auditorium with a seating capacity of 650. Two years later, they enlarged it to its present size of 1000 seats (photo 06).

06 Ozark Opry Auditorium - Highway 54

Now the Ozark Opry plays eight shows a week during the summer, with two performances on Wednesdays and Saturdays; four shows a week from mid April to Decoration Day, and three shows a week from Labor Day till mid October. The rest of the time, the country troupe puts in a grueling schedule of one night stands which range over a five state area.

The only free time Lee and Joyce have is from mid December to mid February but even then Lee travels most of the time looking at other shows and finding new talent.

“I drove close to 30,000 miles this winter and you should see the little girl hoedown fiddler I found in Mountain View, Arkansas. Her name is Paulette Reeves and she’s 17. I tell you she can flat rake a bow. She’ll be with us this summer,” says Lee enthusiastically.

My sister, Pat (Trish) Pryor, was the piano player and occasional singer (rarely) on the Opry during the time the article above was written. After Paulette Reeves arrived on the Opry she and Pat became the best of friends. Here is a photo of them and Lee at one of the out of town shows (photo 07):

-PauletteAndLee_sm.jpg)

07 Pat (Trish), Paulette and Lee

Click image for larger view

Here are some photos copied from the article above with the captions below the photo (photos 08 - 13):

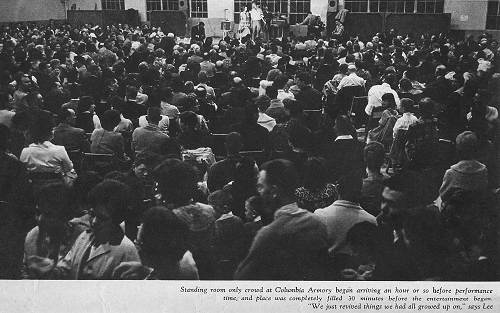

08 Columbia Armory

Click image for larger view

The standing room only crowd at the Columbia Armory began arriving an hour or so before the performance time, and the place was completely filled 30 minutes before the entertainment began. “We just revived things we had all grew up on,” said Lee.

09 Show at Columbia, Missouri

An older couple in Lee Mace’s audience of “home folks and neighbors” howled with laughter at the rustic humor during the Ozark Opry’s performance which was at Columbia, Mo. Later, they bought one of the Opry’s privately produced records and checked with Lee to see where he’d be playing the next week.

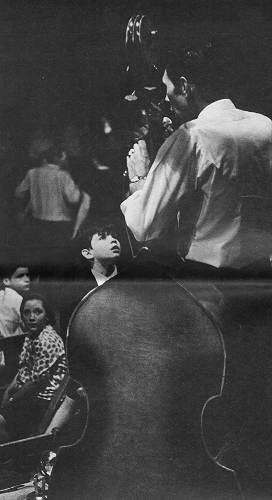

10 Can I sing a Song?

A little boy who identified himself only as Daniel asked Lee if he could sing a song. “Guess we better let him work if off,” Lee told his audience.

11 On Stage Live

The Ozark Opry performers swung into high gear during this lively country number. While no one in the group had formal musical training, most of them can play more than one instrument and all of them take part in the various singing numbers.

(names left to right: Don Russell, Darrell Gordon, Lee Worth, unknown, unknown, Lee Mace, Pat Pryor)

12 Lee Worth - Plays everything on Stage

Lee Worth of Harrison, Arkansas is the new Mace “find” this year, and plays piano and “everything else that has strings on it,” according to his proud boss.

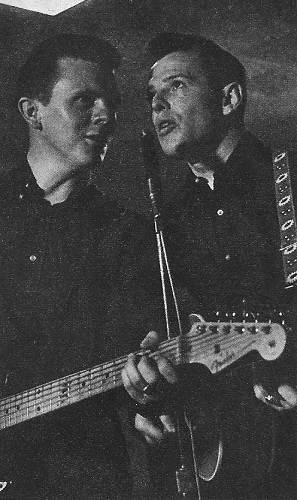

13 Bill "Goofer" Atterbery and Darrel Gordon

Bill Atterberry (left), better known as “Goofer” to Opry fans, and Darrel Gordon team up for a number.

Below is a photo of the entire Ozark Opry cast back home at the Opry auditorium at Lake Ozark taken during the time frame that the above story was written (photo 14):

14 Ozark Opry at Home

Click image for larger view

The performers are named left to right:

Bill Atterberry, Paulette Reeves, Mildred and Harold Moore, Iva Stack, LeRoy Hasleg, Lee Worth, Jim Smith, Lee Mace, Pat Pryor, Darrel Gordon

Quite a few times the reporters who covered one of Lee’s on the road performances were so intrigued by his description of the Ozarks that they wanted to come for a visit themselves to see first hand how life was lived in this area. One of those articles was published in the Globe Democrat in 1964. I was particularly interested in this story because it involved some Miller County people whom many readers will remember or would have known:

Missouri’s Hill People

Shirley Althoff

Globe-Democrat Sunday Magazine, September 6, 1964

There are a lot of things about the natives of the Ozarks that just plain baffle outsiders. Take the Iowa farmer who made a cattle buying trip to the Missouri hill country some years ago. After looking at the scrubby farms with their rock strewn soil, he shook his head.

“How on earth do the people here make a living?” he asked. “Why, I could climb the tallest tree and if somebody gave me all the land I saw from the top, I still couldn’t do it. I’ve got some pretty fine land in Iowa and I got to really scratch to get by.”

“W-e-ll, I’ll tell you,” drawled his guide, “some of the smartest folks in the world live here. I’ll prove it to you. You jest point out any house you want to and I’ll take you in. And I guarantee you there’ll be plenty to eat, the kids’ll be dressed and the people’ll be happy. You couldn’t make a living here but they can. That’s how smart they are!”

The Ozarkian was right.

City slickers, do gooders, even government officials often tsk-tsk over the plain, sometimes shabby little “hillbilly huts” and worry about the children growing up there. Some occasionally even make plans to help “those poor people” improve their lot. But that is because, like the bewildered Iowan, they just don’t understand.

First of all, nobody forces the Ozark hill folks to live up on their ridges or down in their “hollers.” They live this way because they love the country and because it is their way of life. And it is a way of life more akin to the old American pioneer days than anything else. Secondly, while hard cash is pretty scarce they don’t need much to get by. Some make as little as a few hundred dollars a year; others supplement farming by working out as carpenters, laborers, rock layers and such and perhaps average up to $3000 a year. But most of them still raise about 90 per cent of their own food and swap work with their neighbors. In a way it is a hard life (as one of them put it, “Most of us could purty nearly write a book on survival”) but it is the price they willingly pay for independence and the right to fish, hunt, get together with friends or just sit on the porch and rock whenever they like.

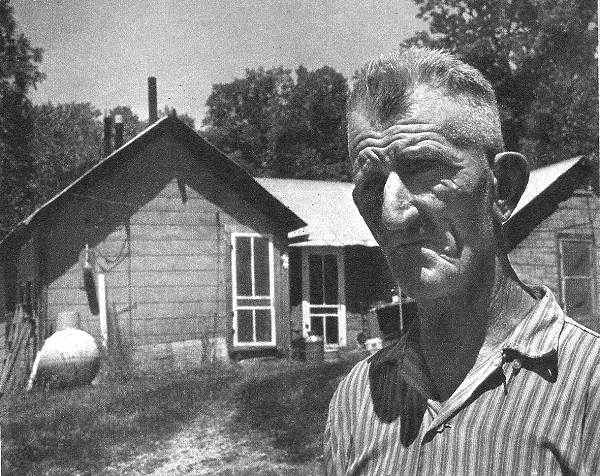

“I was born and raised in these old hills and mountains and I really enjoy it here,” explains 68 year old Clint Ash who has 85 acres near Bear Creek in Miller County. “We ain’t got much money but there’s food enough in the cellar to last five years” (photo 15).

15 Clint Ash

The Ashes’ “cellar” is a small stone shelter built into the side of a hill a short distance from their asphalt sided house. It is filled with countless jars of fruits and vegetables, even fish which Clint caught in the nearby Osage River or Lake of the Ozarks. Mrs. Ash, plump, a good natured woman, estimates she “puts up” about 500 to 600 quarts of food a year.

The Ashes have electricity but they get their water from an outdoor pump and there is no indoor plumbing. Mrs. Ash calls her home “old fashioned” but she points with pride to her electric washing machine and deep freeze (a modern convenience that permits many hill people to eat better the year ‘round now).

Lean and weathered, Clint looks like the typical farmer he is, but he also was elected to the post of County Judge in Miller County for four years. In this capacity, along with two other judges, he accounted for the spending of more than a million dollars a year in county tax money. Clint, who is 69, has given most of his land to his four sons but still has 85 acres near Bear Creek in Miller County

Clint considers himself retired now “except for messin’ in the garden and puttin’ out a little feed for the cows” and has turned over most of his land, about 200 acres, to his four sons. In the past he used to work out some and still recalls his five year stint as custodian at the school in the town of Brumley.

“Many’s the time I got up at 2 o’clock in the morning and walked the four and a half miles from my house to the school to build a fire in the old furnace there. My salary was $35 a month.”

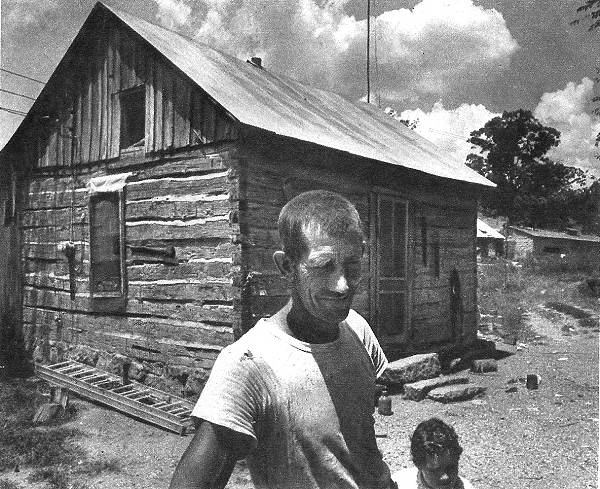

Clint’s nephew, Samuel “Shorty” Ash and his wife and five children live in a 100 year old log cabin in Gravelly Holler which once belonged to his grandmother. Shorty raises broiler chickens, 12,000 at a time, and averages three months a year “workin’ out here and there” as a carpenter or laborer (photo 16).

16 Samuel "Shorty" Ash

Mrs. Ash, Shorty’s wife, estimates she puts up from 500 to 600 quarts of food a year (photo 17).

17 Mrs. Samuel Ash

Over in Elm Springs, another little hollow not far from Clint’s place live Jim and Lucille Blankenship. Their plain frame home is “probably 80 years old or so” and they raise hay and cattle on their 400 acres (photo 18).

18 Jim Blankenship

Like most of the natives, their families have lived in the area for more than a hundred years. Jim, who drives a school bus in the winter to supplement his farming, traveled some when he was in military service and Lucille worked in Kansas City during World War II. Both of them headed home as soon as they could.

“I live here jest cause I like it,” says Jim. “If I get up and don’t feel so good, I don’t have to do nothin’. And if it gets too hot, we can stop workin’.”

“We like to be free and do as we please and not be bossed around,” adds his wife.

For pleasure, they go horseback riding, fish and hunt. According to her husband, Lucille is the real hunter in the family.

“That’s right,” she confesses, “I don’t wash a dish or do a thing till the deer season is over.”

If the Ozarkians are aware that most outsiders wonder about their way of life, they are equally conscious of the fact that the same outsiders could not support themselves in the hill country if they tried.

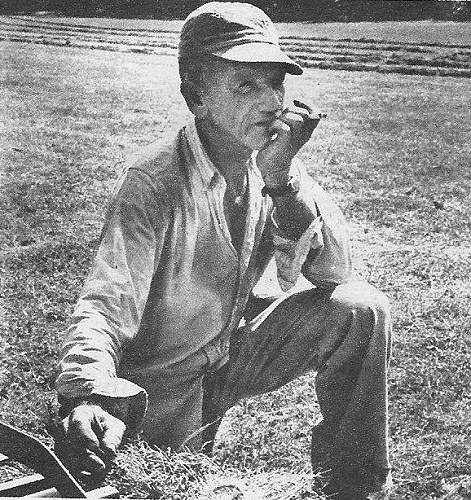

“There’s an old saying down here about strangers who come into this country,” says Robbie Wilson who farms 165 acres in Hickory Holler out of Eldridge, Missouri. “The natives gets their money, the blackjack brush gets their clothes and they go away without anythin’” (photo 19).

19 Robbie Wilson

A quiet, slow spoken man, Robbie is nearing 70 and he and his wife have raised their seven children in their two room tarpaper shanty which perches on the top of a steep hill.

“When I bought this place, I only had 40 acres and I had to conserve land to till. That’s why I put the house here,” he points out.

Robbie says the most hard cash he ever makes in a year is about $500 and some years, he has made as little as $100. It took him 16 years to pay off the $33 he paid for his first 40 acres (“most years I jest kept up the interest”) but bit by bit he acquired more land. All of his children have gone through high school and two of his daughters went on to nurses’ training. And in his little house is a set of world book encyclopedias which all of the youngsters used.

The Wilsons’ oldest boy, Jack, journeyed throughout the United States and served a hitch in Europe with the Army but when he came back he bought 234 acres adjoining his father’s place. The two of them, together with the youngest son, Charles, are fixing up another house on their property into which the family will move when it is finished. The four Wilson daughters have all moved away and the third son, Daniel, works in Kansas City.

“The last years haven’t been so bad with the kids all grown,” says Robbie. But it took all I could scrape together to raise ‘em. I done a little of everthin’…saw millin’, threshin’, workin’ out, even went up to Iowa and worked for the highway department there once’t. But we always ate and always paid our honest debts. This is a poor man’s country, you come into this world poor and you stay poor, but I don’t want to leave.”

The belief that “God helps those that help themselves” is strong in all of these hill folks and while they appreciate aid when it is really needed, they do not like to accept handouts. Many of the old timers remember the depression and drought days of the ‘30’s when government “relief wagons” brought food supplies in. Anybody who could make it on his own wouldn’t take the food, they say.

Proctor Carter, director of the Missouri Department of Public Health and Welfare, agrees.

“These people don’t have much by most standards but they don’t expect much and they manage well on what they do have,” he says.

Many of them dabble in other enterprises in addition to farming. They lease minnow ponds on their property to bait dealers for perhaps $100 a year, keep bees, cut cordwood and quarry field stone. A number run cattle on what they call “speculator land”…land owned by absentee landlords who seldom bother about it. They use the profit from these operations to buy more land or stash it away (“fruit jarred” is the local term) for their old age.

Of course, some members of the younger generation have come down from the hills and settled in the small neighboring towns.

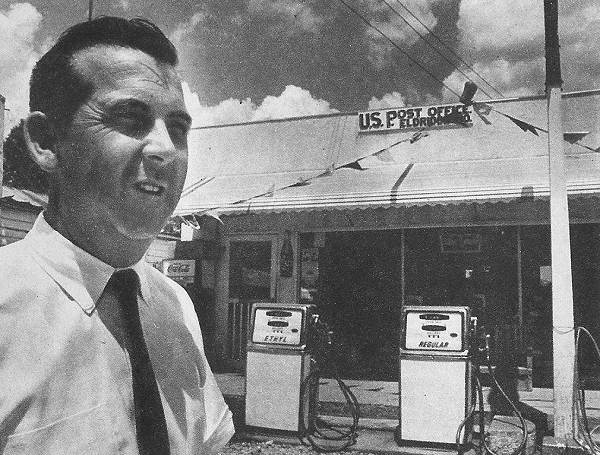

Thirty two year old Harold Moore, for instance, is the postmaster and owner of a small general store in Eldridge (population 100) in Laclede County where his ancestors settled a century or more ago. Harold’s father is a farmer and also the preacher at the town’s little community church whose services follow the Pentecostal pattern. There are no telephones in the town. “We may get ‘em in a year if the company is feeding us the right line,” says Harold (photo 20).

20 Harold Moore

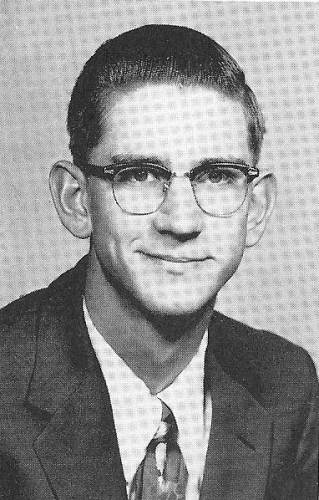

Growing up in Tuscumbia I knew some of the Ash family. Farris Ash, nephew of Clint Ash featured in the article above, was a few years ahead of me at Tuscumbia High School (photo 21).

21 Farris Ash

He was a star center on our basketball team, one of the best Tuscumbia ever had (photo 22).

22 Farris receiving Trophy

Shorty Ash, also featured in the article, was Farris’ brother. Their father was William Elisha Farris (“Dolph"), a brother to Clint Ash.

I also knew Harold Moore and his wife Mildred, who were gospel singers for Lee Mace’s Ozark Opry in the 1960’s (photo 23).

23 Harold and Mildred Moore of Eldridge, Missouri

They were from Eldridge, Missouri about 45 minutes south of the Ozark Opry auditorium at Osage Beach.

What impressed me the most about this article is that people with country roots generally are self reliant, hard working, clever regarding coping and survival skills and usually have the pride and ability to live on their own by their own resources.

One of the projects Lee completed to promote the Lake of the Ozarks area was by creating a series of video "travelogues" featuring the various enterprises and places of interest for the benefit of out of the area tourists who visited here. Here is a sample of one of the videos:

To see the complete series of travelogue videos, visit this page dedicated to this treasured peek in to the Lake area's past. A link to this page is also under the "Yesterdays" menu item on our website. You may need to refresh your browser to pick up this new menu item.

Alan Wright, noted Miller County historian and author of the book, Murder on Rouse Hill, also is a skilled photographer who has put together one of the largest collection of photos of Miller County ancestors (photo 24).

24 Alan Wright

Alan, who is a graduate of Eugene High School has deep Miller County roots. For more than forty years he has used special techniques to photograph old portraits, photos and paintings. Copying friends’ and relatives’ priceless photos right in their homes, these forty-five year old images compare favorably with today’s high resolution scans. It is our great good fortune that Alan has consented to allow us to place these historical and high quality images of paintings, portraits and photos of Miller County citizens of the past on our website. You can read more about Alan’s project in his own words at the Gallery Introduction page.

And you can access the photos from the main Gallery page.

That’s all for this week.

Joe Pryor

Previous article links are in a dropdown menu at the top of all of the pages.

|