|

Monday, August 20, 2012

Progress Notes

This week we are very privileged to have the opportunity to read an exceptionally well written and intriguing story authored by Miller County native Alan Wright, now a resident of St. Louis.

Alan Wright The narrative Alan brings to us is a true one revolving around the tragic drowning in 1937 of two young Miller County natives in a rock quarry near Alan’s home located midway between Etterville and Eugene.

Alan introduces the story by recounting childhood memories of pleasurable family outings to the quarry, followed by an exceptionally interesting history of the Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company, the original owners of the quarry. Included also in the beginning of the narrative is an interesting history of the origin of the town of Eugene. But as the story progresses you will find it is more than just an historical essay, much more. This is an extremely engaging and interesting narrative you won’t soon forget; and as Alan comments, it is “A story of hope, failure, and tragedy.”

Here are quick links to the various parts of the narrative:

Part I - Trips to the Rock Quarry - the Wright Kids' Dream

Part II - The Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Company

Part III - Tragedy at the Rock Quarry

The Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company

A story of hope, failure, and tragedy

By: Alan Terry Wright

Part I

Trips to the Rock Quarry—the Wright Kids’ Dream

There was never a time in my boyhood that the prospect of “going to the rock quarry” with my older brothers and sister didn’t promise adventure and the delicious prospects of fishing, berry picking, cliff climbing, and looking for fossils.

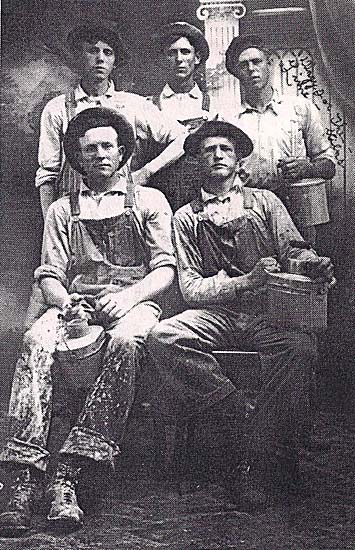

Garsy Wright family, 1938, a year after 1937 Rock Quarry

tragedy. Garsy stopped riding the kids on his back while

swimming there. L-R, Ruby, holding Merlin, Glennie, and

Garsy, holding Bernie.

L-R: Glen, Merlin, Alan, Patricia, Bernie, Ruby and Garsy Wright

Circa 1952, at Uncle Warren's house, after returning from Shepherd of the Hills trip

Somewhere in our untroubled minds, we may have wondered about how the quarry got there, whose sweat and toil operated it, and why it had been so long abandoned. But we didn’t dwell upon those enigmatic subjects. Strips of twisted, corrugated “sheet iron,” abandoned machinery of unknown uses, and concrete footings with protruding rusty bolts supporting nothing could be found among the high weeds and saplings. They merited only passing glances and an occasional, “I wonder what that did?” No, my siblings and I had purposes more pressing. Filling our mouths (and sometimes little lard pails) with wild strawberries, blackberries, gooseberries, and plums were pleasant occupations. And later, capturing giant “tobacco spitting” grasshoppers to be imprisoned in a fruit jar until needed for bait occupied our energies. Schools of perch, along with an occasional large bass, swam leisurely by oblivious to our excited cries. Easily observed in the translucent, bottle glass green waters, they swam with a certain careless arrogance, as if to say, “We’ve met and defeated better anglers than you juvenile amateurs---waste your time if you wish.”

Part of the rock quarry’s allure was that it wasn’t easy to get there. In order to reach its water’s edge, several hazards need be overcome. The Wright house sat just off U.S. 54, midway between that road’s junction with State Highway 17, and the quaint village of Etterville, some three miles west.

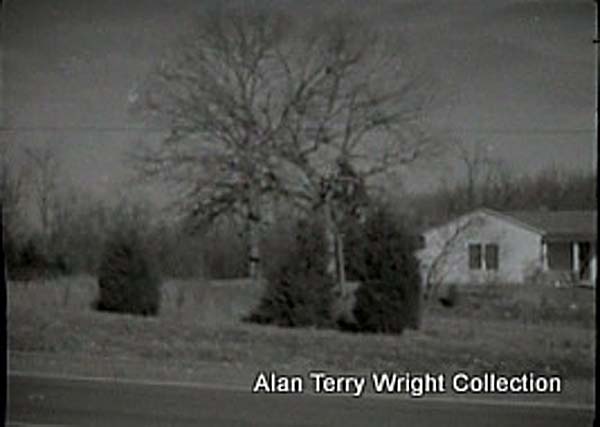

The Garsy & Ruby Wright home, U.S. Highway 54, near Eugene.

This photo was taken the day Ruby Wright moved to "Melody Lane," between Tuscumbia and Iberia,

in November of 1972. It was from this house that the Wright's made many enjoyable hikes to the old

"Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Company" quarry about one half mile south. The house,

located on U.S. 54, near Eugene, had been acquired by the Missouri Highway Dept. for widening of the

road to four lanes. Demolition likely began within days. Garsy Wright, who built the house,

driving every nail, was spared seeing his handiwork demolished. He had died in 1971.

The new Datsun 240Z in the driveway was Alan & Mary Wright's.

The old oak tree in the yard of the Garsy Wright house, November 1972.

As a kid, climbing to the top of this tree, Alan Terry Wright could see all the way south to the

"Rock Quarry." It was from this house that the Wright's made many enjoyable hikes to the old

Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Company quarry about one half mile south. Our trek began by running southward across the busy highway (look out for cars) and crawling under a sturdy three strand barbed wire fence (watch for snakes). We then crossed at least two forty acre fields (avoid any grazing bulls), before reaching the Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific tracks. When our parents, Garsy and Ruby Wright, started building their house in the summer of 1932, those fields had belonged to the Sterling Jenkins and Oliver Golden families. More recently, the place had been occupied by Jesse “Bud” Logbrinck, his wife, Peggy, and son, Gary, whom I liked and played with as a first grader.

Arrival at the railroad tracks presented more fence obstacles. Pulling wires up for brother or sister to crawl through without snagging cotton threads, was a necessity. The smell of creosoted ties and the distant whistle of a steam locomotive laboring up the steep grade out of nearby Eugene focused our minds. But the “look out for trains” and “stay off the tracks” parental entreaties yielded to the joys of walking the rails; gluing ears to the tracks listening for vibrations; and the knee-knocking thrill as the whistle blowing, thundering, hissing, smoking, behemoth rushed by. Men at each end of the train, clad in striped bib overalls and matching caps, waved heartily and we waved back----life was good!

The abrupt cessation of noise and the disappearance of the caboose signaled time to cross a last fence onto the quarry property. We didn’t worry about trespassing. No signs were posted and “word” was that ownership of the property, in dispute for some time, rested with a family heir residing in far-away California. Unworried, we trudged on, following a weedy, chat covered road up the hill and around a bend to the south opening of a giant excavation. In the background, removal of hundreds of tons of limestone rock had left a jagged circular cliff, fifty to sixty feet in height. In the foreground, an excavated hole of likely equal volume had filled over the years with clear water, creating a lovely little lake. Adults had told us that the pool, approximately two hundred feet in diameter, was eighty to ninety feet deep and fed with underground springs. Later, it would be learned this depth was an exaggeration.

Alan Wright stands near the southeast entrance to the Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Co.

rock quarry near where Ruby Colvin, Homer Walters, and Gerald Haynes entered the evening of

July 16, 1937. Photo, May, 2012. Although my dad in his younger days had dared to ride my older brothers as toddlers on his shoulders while swimming in the Rock Quarry, we were commanded not to swim there. Patricia and I always obeyed, but oh, how inviting those cool waters appeared on a hot summer’s day! My brothers, Merlin, Glennie, and Bernie, recall swimming there before I could remember but only after they had become strong swimmers. Dad told us that once while riding Glennie on his back, the little boy had clamped his arms so tightly around his daddy’s neck that he nearly lost consciousness. They both would have surely drowned. Having struggled to get them both out, dad never swam there again.

Alan Wright's school friend, Patricia (Bittle) Millholland, at northeast edge of Spring Garden Marble

and White Lime Co. rock quarry. Pat helped Alan arrange visit with property owners and locate the site.

Photo, May, 2012. As the hours waned on with only a couple of small perch on our stringer and the sun’s departure over the bluff’s rim creating long shadows, we began to think about home. Soon the bull frogs, populating the forest of cat tails near our fishing spot, would begin their evening chorus. Tired and thirsty, we collected our belongings, pulled our little fishes from the water, and began our departure.

The Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Co. quarry as it appears in May, 2012.

Having "gone back to nature" from its industrial use, it appears as a lovely

natural lake in the woods. Photo, May, 2012. Rounding the bend near the small, shallow “tail” of the otherwise deep waters, we stopped for a last, lingering view of this magnetic place that so captured our youthful imaginations. Shouting “Good Bye!” several times, we heard the wavering, but distinct echoes speaking to us from the bluffs. Good bye!...Good bye!...Good bye! We suddenly thought of the other reason we didn’t swim in that quarry.

It seemed that many years before, a young woman and a young man, while visiting late one evening, had drowned in these dark, placid waters. Finding herself suddenly plunged in deep water and unable to swim, the young lady clung desperately to her would-be rescuer, reputed to be a strong swimmer. After a frantic struggle, they both slipped below the surface, spiraling to the bottom. In only a few moments, their young lives had been taken by the Rock Quarry’s cold and indifferent grasp. Later that night, a recovery party’s powerful search light penetrated the clear waters and disclosed the couple’s lifeless bodies lying on the bottom in some thirty feet of water. Arms in a tight embrace, seemingly as lovers, their fates forever entwined.

The Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Co. quarry.

View from northwest corner overlooking location of the drowning of

Ruby Colvin and Homer Walters, July 16, 1937.

This peaceful place is now seldom visited. Photo, May, 2012. Shivering for a moment, the Wright kids turned and hurried home to a worried dad and fretting mother. Some sixty years later, the names of those young people claimed by the Rock Quarry finally became known to us. Later, more of their story.

The Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company

A story of hope, failure, and tragedy

By: Alan Terry Wright

Part II

The Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company

[Please note that personal pronouns like “I”, “me”, “my”, “our”, ”we”, etc., refer to the author and the author’s family]

The town of Eugene established

In 1992, Bonnie Spalding Jenkins published a wonderful booklet, called Eugene, Missouri, The Town that Lived (and Died) With the Railroad. In it, she says that the right of way and roadbed of the Chicago, Rock Island and Pacific (CRI&P) rail line through the land that would become the town of Eugene were completed in 1901. By 1903, the track was laid, and in that year, the town of Eugene was platted.

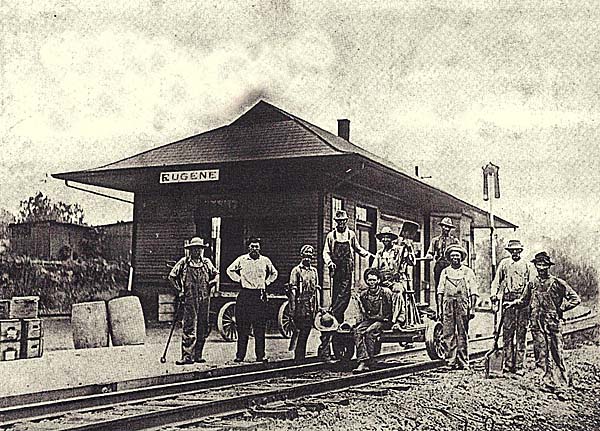

CRI&P Station, Eugene, MO, about 1910. Railroad section gang members are unknown

except George T. Loveall, second from right. Station agent in white shirt might be Bill Anderson.

Source: "Eugene, Missouri", Bonnie Spalding Jenkins, 1992

Eugene Train Station - 1957

Photo Credit:

Howard KilliamBonnie confirms an account given me by my cousin, long time Miller County educator, Maude Wright, that the town was named for Maude's "Uncle Eugene Simpson" who donated part of the land for the new "metropolis." Maude added the interesting detail that the names of Eugene Simpson, John Melton and Charles Jenkins were placed in a hat to decide who had "naming rights." Melton won, but Bonnie Jenkins says that the name "Melton" was rejected by the US Post Office. Eugene Wright then won by default. Thus the town would forever carry the "Eugene" moniker, one of only two "cities" in the U.S. of the name. Eugene Simpson was married to Fanny Augusta Alaphaier Wright, my father, Garcia "Garsy" Wright's first cousin.

Eugene and Fanny (Wright) Simpson

Photo courtesy of Linda Walden

Eugene and Fannie (Wright) Simpson Headstone at Rocky Ford, CO

Photo courtesy of Linda Walden By 1904, the CRI&P was running excursion trains to St. Louis, permitting Eugene and Eldon area residents to partake of the wonders of the St. Louis World’s Fair.

Eugene Simpson, the man for whom Eugene, Missouri was named, and friends pose in front of an arched, cut stone culvert, under construction in about 1901-1902, and located about one mile east of the CRI&P tunnel at Eugene. Railroad buff and former Miller Countian Jeff Cooney says that such cut stone culverts (as opposed to poured concrete) are rare on the St. Louis-Kansas City line. The tunnel was completed, track was laid, and trains first began running on the new line from St. Louis to Kansas City, Missouri in 1903. Eugene Simpson married Fanny Augusta Alaphaier Wright (daughter of Henry Wright and Minerva Jane Melton Wright and granddaughter of James Lawrence Wright and Elizabeth Mace Thompson Wright) in 1895. Eugene Simpson is likely the young man gesturing on the left. The photographer was probably Eugene's wife, Fanny. The tunnel, the longest on the St. Louis-Kansas City line, is 1,667 ft. in length. Provenance of photo: Eugene and Fannie's son, Arthur M. Wright.

Photo courtesy of Alan Wright

Arched, cut-stone culvert under Chicago, Rock Island & Pacific grade about one mile east of the CRI&P tunnel at Eugene, Missouri. Photo by Jeff Cooney, March of 1992, about 90 years after a photo of a group of young couples, including Eugene Simpson (namesake of the town of Eugene) was taken at this same location in about 1901-1902.

Recent Photo of CRI&P Tunnel - East Portal

Recent Photo of CRI&P Tunnel - West Portal Suddenly, everything was “up-to-date” in southern Cole County and Northern Miller County. The town of Eugene straddles the Miller and Cole County lines and when I was a schoolboy, it was told that the county line actually ran between the Eugene School’s main building and the gymnasium, the two buildings being connected by an underground “tunnel.” But that’s another story.

Old Eugene school and gymnasium, 1953. They were connected by an underground tunnel.

Did the Miller County boundary line run between the buildings?

Unlikely, since the District is called Cole R-V.

Source: Alan Terry WrightThis story is about the production of white lime and the creation of a rock quarry on the Rock Island line, midway between the newly minted town of Eugene and the longer established village of Etterville, some four miles west.

St. Louis corporation formed with an eye on Miller County

On the third day of March, 1902, five businessmen met in the City of St. Louis and adopted Articles of Incorporation for a new company called “The Colorado Lime Company.” The Corporation was initially capitalized with $10,000 of stock, at $100 per share, “bonafide subscribed for and the whole amount….paid up in lawful money of the United States…” The original incorporators’ names and their occupations, as noted in the U.S. Census of 1900 and St. Louis City Directory, 1901, follow:

George Smith Meenach, age 36--Grocer

Albert Weir, age 52---President, A. Weir Produce Co.

Isaiah Pillman, age 39—Pillman Bro. Produce Co.

Austin Louis Pollard, age 41—freight agent

Joseph Pillman, age 44 (Per Isaiah Pillman, his Trustee)—Pillman Bro. Produce Co.

What brought these five people together? Why did they want to get into the lime producing business? Why did they choose to call the newly formed Missouri company the “Colorado Lime Co.”? After 110 years, the answers can only be speculative.

Meenach, Weir, and the Pillman Brothers were all in the grocery and produce business. They were likely personal acquaintances, having businesses in the North Third Street and North Broadway areas of St. Louis City. This “north riverfront” commercial and industrial area remains, to this day, the center of the wholesale produce industry in St. Louis.

Austin Louis Pollard, born and raised in Mississippi, was a railroad freight agent. Which railroad? Possibly the CRI&P. By 1920, A.L. Pollard listed his occupation in the U.S. Census as “Railroad Superintendent,” and at the time of his death in 1921, he was listed as the “Chief Car Accountant” for the Mobile and Ohio Railroad. Clearly, Pollard was a railroad man, moving in those circles. He would likely have had knowledge of the CRI&P’s opening of a new line from St. Louis to Kansas City and “scuttlebutt” about possible mining opportunities along the new right-of-way.

The name “Colorado Lime Company?” Perhaps an original intent to manufacture lime in the State of Colorado. Maybe just a fanciful name. Who knows? What we do know is the company’s name was changed in 1911 to the “Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company.” This name better reflected the company’s quarry and lime kiln operation located about two miles south of Spring Garden in Miller County and the finding of a substantial marble deposit there.

The singular lack of mining and/or lime making experience of members of the board of directors of the new company certainly stands out. A group of grocers and produce wholesalers, along with a railroad freight agent, going into the mining and lime manufacturing business, and investing substantial amounts of their own money, seems peculiar. Who of their acquaintance had the glib salesmanship to convince these otherwise solid and cautious businessmen that such an operation was feasible? And that it could be designed, constructed, and operated on a scale sufficient to be profitable?

My candidate for the role of “Founding Father” of the Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company would be Austin Louis Pollard, who somehow became aware of the opportunity. With his southern charm and eloquence, Pollard sold the deal to his wholesale grocer friends with whom he was acquainted in his job as a rail freight agent. As noted below, the director/investors in the Company paid $40,000 of real money as equity into the operation. How much additional money was borrowed, one cannot say, but assuming a roughly equal debt/equity capitalization, the total investment may have been as much as $80-100,000.

According to on-line inflation calculators, that amount would be equivalent to $2,631,000 in 2012 dollars. No mean sum---to be sure.

Why did the Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company choose Miller County?

A major clue as to why a group of St. Louis businessmen was willing to make a large capital investment to exploit mineral assets near Eugene, along a brand new railway, is found in an excerpt from:

The Geology of Miller County, by Sidney Ball and A.F. Smith, Missouri Bureau of Geology and Mines, Jefferson City, Mo, dated 1903, Chapter XII:

Miller is one of three counties which have been surveyed since November, 1901. It is one of the most centrally located of the counties of the State and constitutes a very desirable point from which to begin the systematic stratigraphical work, which it is intended to continue into all parts of the State. This is the second county of the Ozark region for which a very detailed survey has been made. In 1871 the Bureau published a reconnaissance report on Miller County by F.B. Meek.

Lime

Up to the present time lime burning in this county has been carried on in a very primitive manner. In the rural districts each farmer makes his own lime by heaping and burning together wood and limestone boulders which have been covered with earth and sod. Sometimes a hole is dug in the hillside and in this the lime is burned.

Mr. J.E. Sullen (sic, Sullens) has operated a kiln east of Etterville for eight years. He states that during this time he has sold $525 worth of lime, of which nearly one half was produced in 1900. The entire output was sold to farmers and townspeople in the immediate vicinity. Abandoned or temporary kilns are found in many areas. (Author’s underline and emphasis)

Although Mr. Sullens’s $525.00 in lime sales doesn’t seem like a lot, the reader should be reminded that using the inflation calculator from above, this amounted to some $13,650 in 2012 dollars, or about $1,700 per year---a nice little “chunk of change.” More importantly, the location cited is likely the exact location of the quarry/kiln business developed only a few years later by the Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company.

[Hereinafter, for convenience, the Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company and “the Company” will be used interchangeably.]

It seems pretty clear that the State’s report noting Mr. Sullens’s little business and its potential for expansion did not go unnoticed. With the new CRI&P line giving access to big city markets, both east and west, a “big ideas” man like Austin Louis Pollard could easily have used the report to persuade investors and motivate formation of the Company.

To gain more perspective of the Company, below is a chronology drawn from records still on file with the Missouri Secretary of State’s Office:

March, 1902—incorporated as the “Colorado Lime Company” with the five original directors noted above and having a paid-in capitalization of $10,000. The CRI&P tracks would not be laid by the eventual site of the Company’s operations, west of Eugene, and south of Spring Garden, until 1903.

March, 1905—Directors of the Company met and authorized increasing the capital stock of the company from $10,000 to $30,000. A.L. Pollard is noted as being Chairman of the Board and George S. Meenah as Secretary.

April, 1905—Directors of the Company met and increased the number of directors from five to seven. The new directors (presumably additional investors who had helped increase the company’s paid in capital from $10,000 to $30,000) were as follows:

John F. Gravel, age 27—grocer

Robert W. Gartside, age 46---grocer

March, 1906—Directors of the Company met and authorized increasing the capital stock of the company from $30,000 to $40,000. In addition, John F. Gravel and Robert W. Gartside were chosen as Chairman and Secretary, respectively.

May, 1911—The Company changed its name from “Colorado Lime Company” to “Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company.”

December, 1914—The State of Missouri, Department of State, issued a “Forfeiture of Charter” order for the Company, declaring its charter forfeited and its “corporate existence terminated.” The reason cited was failure to adhere to several provisions of a newly enacted Missouri corporations Act dealing with “annual registration, supervision, and filing of annual reports certain corporations…”

January, 1915—Josiah Pillman, President of the Company, filed an affidavit with the Missouri Secretary of State’s Office, asking that the Forfeiture of Charter of December, 1913 (Sic, 1914) be rescinded, with payment of $25.00 fee.

January 1922—The State of Missouri, Department of State, again issued a “Forfeiture of Charter” order for the Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company, declaring its charter forfeited and the “corporation dissolved.” No application for rescission of this forfeiture was ever filed and the corporate history of the Company ended.

The Company brings in Robert W. Gartside

Undoubtedly from its incorporation in 1902 until fully capitalized in 1906, the Company was finding its way and learning that its ambitious plan to quarry limestone and manufacture white lime would cost considerably more than first estimated. The delays and miscues always associated with start-ups must have been part of the narrative.

The addition of Robert W. Gartside to the Company’s board in 1905 helped energize the operation and get it “up and running.” Mr. Gartside may have been a “grocer” in 1900, but by 1907, the CRI&P had established and published a “stop” named “Gartside” at the site of the Company’s quarry and kiln. This honor was likely bestowed by the Company’s board of directors acknowledging Gartside’s hands-on interest in the operation and his injection of the capital necessary to get into production.

Abandoned Rock Island line tracks at/near the stop called "Gartside"

that once served the Spring Garden Marble & White Lime

Company in the 1910's. View is westerly, toward Etterville.

Photo, May, 2012.The U.S. Census of 1910 no longer listed Gartside’s occupation as “Grocer,” but as a “manufacturer of lime” and as an “employer.”

How is it known that “Gartside” was an established stop on the CRI&P by 1907? A chatty little entry in something called The Railroad Telegrapher, 1907, p. 1541, states the following:

“Former Agent C.H. Palmer of Freeburg (on the CRI&P, a few stops east of Eugene), who has been in business at Eldon for some time, was at Gartside August 19th ‘prospecting.’ (Author’s quotes and emphasis) He expects to re-enter the railroad service again in the near future.”

Gate entry on south side of the abandoned CRI&P right of way to the old Spring Garden

Marble & White Lime Company property at "Gartside," Miller County, MO. At/near this spot

once stood an overhead bridge built by the Rock Island to facilitate operations there. The bridge

eventually burned and the road leading west to the quarry and kilns from the Tuscumbia-Spring

Garden Road reverted to the property owner.

Photo, May, 2012.Exactly what Mr. Palmer was prospecting for is lost to history but the matter-of-fact use of the name “Gartside” suggests the Company was routinely producing and shipping its lime by 1907. It doesn’t seem unreasonable to conclude that lime was being manufactured and shipped as early as 1906, when the company got its last $10,000 of capital, but almost certainly by 1907. One can easily imagine Mr. Gartside dividing his time from his grocery business with day-trips on the Rock Island out of St. Louis to his namesake station, overseeing and auditing the Company’s operations. When Mr. Gartside died at the age of 93, his 1949 death certificate noted that he was retired from the “Glenco Lime Company.” There was no mention of him ever being a “grocer.” He had turned the lime business into a career.

The Company’s Business, 1910-1911

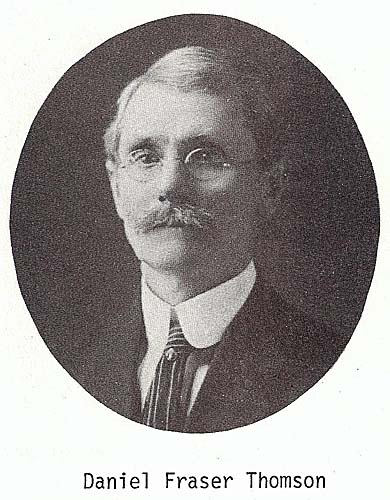

Historian and scholar Daniel Fraser Thomson, a cousin of mine, prominently mentioned the Company’s kiln operation in his “History of Miller County,” published in the Miller County Autogram, December 21, 1911. The article can be found on the excellent website of the Miller County Historical Society, Tuscumbia, Missouri.

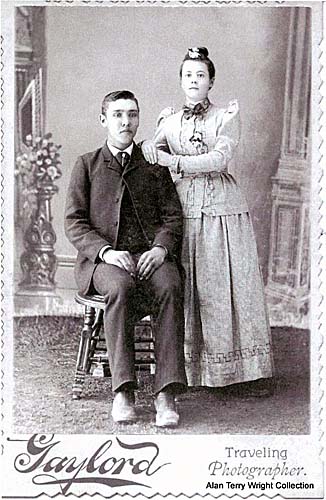

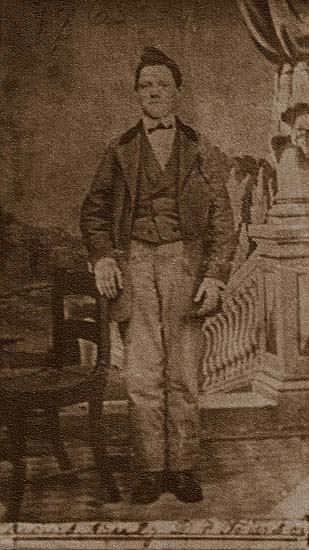

Daniel Fraser Thomson, son of Thomas Thomson and Kerenhappuch Sellers.

In 1864, when 14, he lied about his age and joined the Union Army.

He was mustered out of the 48th Reg., Mo. Volunteers, March 21, 1865

at Camp Douglas, Chicago, IL. This picture was likely taken at that time.

Daniel Fraser Thomson; soldier, teacher, newspaperman,

Asst. Missouri Adjutant General, active GAR member, and historian. An enthusiastic booster of his home county and many civic and family causes, “Dan Fra” said:

Miller County has lime “to burn” and the quality is everywhere unexcelled, but at only one point in the county has the lime industry become of commercial importance. But for more than half a century private kilns for private use have been burned in all parts of the county when lime was needed. On the C.R.I. and P. railroad (Chicago, Rock Island, and Pacific railroad) near Spring Garden, a little more than two years ago, the “Colorado Lime Company” was organized and equipped on a fairly extensive scale, but by reason of developments the company recently held a meeting at its offices in St. Louis and voted to change the name to the “Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Company,” and announced its intention to expend $100,000 for the development of machinery for the production of marble. The marble, which is declared to be a high graded gray marble, underlies the limestone. “Experts have reported that the marble deposit extends under nearly all of the property, which is 52 acres in extent, in strata from 4 to 8 feet thick, and borings showed the deposit to be 60 feet in thickness.” The lime kilns will be continued in operation.

There is no evidence that the Company ever raised the additional $100,000 that it needed to mine marble from the Gartside quarry or ever unearthed any of the marble it found lying deep beneath the already quarried limestone. Is there a twenty first century mining opportunity waiting for a well-financed entrepreneur? To get started, nearly one million gallons of water, now forming a small lake, would need to be pumped out.

Although Robert W. Gartside undoubtedly took an active interest in the quarry and kiln operations, a family well represented on the board of directors had their man managing the day-to-day operations. His name was Abraham “Alan” Pillman, younger brother of board members Josiah and Isaiah Pillman. Living in Washington County, Alabama and listed as a “farmer” in the 1900 U.S. Census, he and his family were living at the site of the Company’s quarry and kiln by 1910. Alan’s occupation was listed as “Superintendent of Lime Factory.”

Who was Mr. Pillman superintending? A search of the 1910 U.S. Census of Miller and Cole county townships surrounding the Company’s kiln disclosed the following “lime kiln” and “stone quarry“ workers:

O. Berry Bond, 21

Oscar Belshe, 21

Arthur M. Bond, 19

James L. Bond, Jr., 22

Isaac Jenkins, 33

Edgar M. Williams, 43

Henry Procter, 41,

John Cross, 27 (stone quarry)

Edward Spalding, 22

Walter Bond, 29

George Loveall, 51

Charles McFall, (foreman, stone quarry)

"Dingey for the lime kilns" inscription on photo of workers of the

Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Company on the CRI&P,

between Eugene and Etterville, MO.

Back row, L-R, Claude Buster, son of Virge Buster; Alfred Jenkins,

son of Ben and Sarah Jenkins; and Edgar Loveall.

Front row unknown, but may be among the list of names of Cole and

Miller County "lime kilnworkers" in 1910. Photo circa 1910.

Source: "Eugene, Missouri", Bonnie Spalding Jenkins, 1992.The 1910 U.S. Census shows the Alan Pillman (superintendent) and Charles McFall (foreman) families living close by the family of William J. Sullens, 59, including his wife, Barbara, 41, and their children, Raymond, 4 and Mildred, 2.

Helen, Nellie, Abraham, Lael, Mamie, Stanley, and Richard Pillman.

Photo dated 1907, likely taken at their rural home in Miller County, Missouri.

Abraham, also known as "Alan", was the Superintendent of the Spring Garden Marble and

White Lime Co. quarry and kiln on the CRI&P Railroad near Eugene, Missouri.

Source: Internet genealogy posting.As a child in the 1950s, I recall hearing that the Rock Quarry property once had been the “home place” of our neighbor, Raymond Sullens. A 1930 plat map of Miller County confirms this. It appears that Raymond’s father, William Sullens, sold some 44 acres on the north end of his 121 acre farm to the Company. This acreage was bisected by the CRI&P right-of-way. When I knew Raymond and his family in the 1950s and ‘60s, he could undoubtedly have described the history of the Company’s kiln and all its operations in detail. Raymond was a long-time employee of the CRI&P, serving as foreman of a “section gang” working out of Eugene. A recent visit with Raymond’s daughter, Ruby (Sullens) Balsley and her husband, Tom, retired and living in Columbia, MO, helped shed some light on the kiln’s operations.

Ruby and Tom Balsley said that there was once a road leading to the kiln off of what was called “Dairy Lane” in the ‘60s and is now called “Abbott Road.” Dairy Lane, which I’m sure has a fancy 911 locator name now, led south from the intersection of Highways 54 and “AA.” It passed the Farris, Sullens, Graham, Jenkins, Bittle, and Gray farms, crossing the Rock Island line twice, and circled into the west side of Eugene by the school. The “Kiln Road” led westerly off Dairy Lane, going in front of where the Bob Graham house now sets, and after a half mile or so, ended at the Company’s property, lying on both sides of the CRI& P line. A wooden overhead railroad bridge at “Gartside” permitted uninterrupted access to both sides of the Company’s quarry and kiln operations. Ruby said her father told them that the bridge eventually burned and the Rock Island offered to replace it, but by then the kiln was closed and the adjoining property owner was anxious to close and fence off the road. A 1930 Plat Map of Miller County shows that the road likely ran across some 177 acres then owned by George L. Jenkins. Interestingly, the same map shows the Company’s property, some 44 acres, still in the name of “Joe Pellman,” undoubtedly the same “Josiah Pillman” who was one of the Company’s directors. However, Josiah Pellman had been dead since 1924 and the Company out of business for at least eight years.

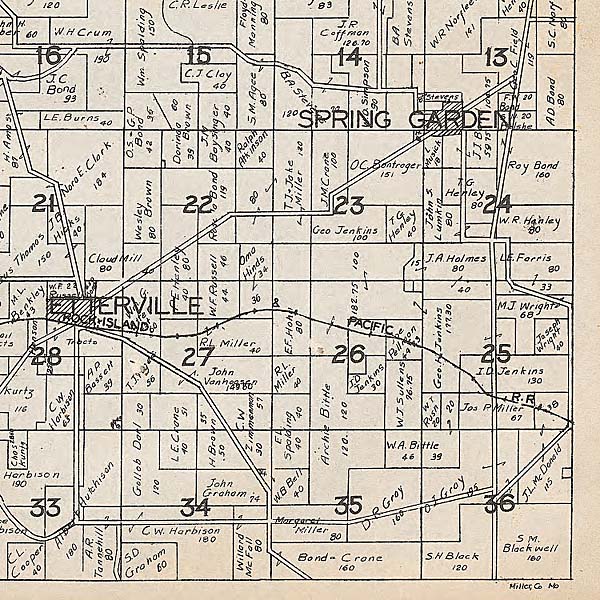

Location of old Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Co. on CRI&P Line.

See "Joe Pellman" in Section 26.

Source: Plat Book of Miller County, W.W. Hixson & Co., 1930.The making of lime requires the heating of limestone, calcium carbonate (CaO3), in an enclosed kiln, to a very high temperature, releasing carbon dioxide (CO2) and leaving calcium oxide (CaO), a very useful product for many industrial purposes. The addition of water (H2O) to CaO creates calcium hydroxide CaOH, or hydrated lime, used in mortars and plasters and water purification.

It is impossible to precisely describe the operation of the Company’s lime kiln at Gartside, nearly a hundred years after its closure. But limestone was surely blasted with black powder or dynamite from a rock face, crushed in a pulverizer to a suitable size, and then fed into a large, heavy, metal tank—the kiln. We don’t know if the kiln was heated with locally cut wood, or perhaps with oil brought in by tank car. For efficiency, lime kilns are heated not just from the bottom but from the sides. An opening at the top permits the release of carbon dioxide. Core sample tests likely indicated when the batch was finished and the lime may have been dropped from the bottom of the kiln into a bagger or perhaps augured in bulk into a suitable rail car. My recollection was that there was a high, steep berm leading north from the back of the quarry toward the railroad tracks. My sister, Patricia, and sister-in-law, Ruth (Copeland) Wright, once took refuge from an angry bull by climbing up this steeply sloped artificial hill. I was told that there was once a small gage rail track along the top of the berm, permitting transport of limestone to where it could be dumped down into a crusher or perhaps, directly into a kiln.

The only known picture of the Company’s lime kiln workers reveals that they were mostly very young men---this extremely hard work was not for senior citizens. Quarries are inherently dangerous workplaces and the addition of water and caustic chemicals surely added to the hazards and discomforts. Splotches of limewater on their overalls and lime dust on their faces are proofs that they indeed were “putting in a day’s pay for a day’s wages.” And more.

As a youngster, I was told stories of prisoners working at the site and that at least one was killed by accident or murder. I will leave the truth or falsity of that claim to other researchers. I was also told, perhaps erroneously, that lime and crushed rock for the construction of U.S. Highway 54 through the area in about 1932 were obtained from the Gartside quarry. This would have been at least ten years after the Company went out of business. Such a re-start for only a temporary need seems difficult to imagine; but when the government is paying for it, all things are possible. There may be senior Eugene area residents who could confirm or deny such stories.

The end of the Spring Garden Marble and White Lime Company likely came before 1920, although the State’s final dissolution of the Company didn’t occur until early January of 1922. The U.S. Census of 1920 shows Superintendent Alan Pillman in St. Louis working as a commission salesman, likely for his older brother’s produce company. Charles McFall, the quarry foreman in 1910, and his wife Lillian and children Mabel, Charles and Clara, are nowhere to be found anywhere in the 1920 census--certainly not in Miller County, Mo.

Why did the Company go out of business? Likely for the usual reasons: lower cost competition; oversupply and dropping prices of such a commodity; or good old fashioned mismanagement. Maybe the original investors, of whom three were dead by 1921, had withdrawn their capital, creating cash flow problems. Maybe the Company simply ran out of easily accessible limestone. Maybe they blew their capital on a misguided attempt to recover marble from an ever deepening and difficult to access quarry bottom. As they blasted deeper and deeper below grade into the rock strata, water was surely infiltrating into the hole, requiring constant pumping. Eventually this water would rise thirty five feet to claim the lives of two naïve and unwary young people July 16, 1937.

The Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company

A story of hope, failure, and tragedy

By: Alan Terry Wright

Part III

Tragedy at the Rock Quarry

[Please note that personal pronouns like “I”, “me”, “my”, “our”, ”we”, etc., refer to the author and the author’s family.]

A tribute to Ruby and Homer

As I sit here typing, I’m reminded that exactly seventy five years ago today, the evening of Friday, July 16, 1937, two young people with most of their lives ahead of them drowned in the abandoned Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company quarry midway between Eugene and Etterville, Missouri. As a child and as a young man, I never visited the quarry without recalling what happened and my parents’ admonition to never swim there. The water is cold and deep. Around its perimeter, entry into the water leads to abruptly steep drop-offs, plunging the unsuspecting to “over–your-head” depths. Without help, non-swimmers, once in the water, may never get out.

By the early 1950s, the names and images of the two souls whose lives were extinguished by the quarry’s merciless waters were unknown to most visitors to the quarry including my brothers and sister. Although we relished going there, the place had a quiet, somber feel to it. We approached it with care and were respectful of its frightful possibilities. We never left it without wonderment and a silent prayer for the two who came, but never left. Their names were:

Homer Walters

and

Ruby Colvin

And below are their images:

Ruby R. Colvin, daughter of Peter and Margerie E. (Wyrick) Colvin, Etterville, Missouri. Born April 27, 1916; Died July 16, 1937 in a tragic drowning incident in an abandoned quarry near Eugene, Missouri.

Photo courtesy of her sister, Bonnie (Colvin) Rhoades |

Homer M. Walters, son of George & Lola (Perkins) Walters, Fremont, Missouri. Born Sept. 13, 1911; Died July 16, 1937 in a tragic drowning incident in an abandoned quarry near Eugene, Missouri.

Photo courtesy of his nephew, Don Washburn. |

If alive, Ruby would be 96. Homer would be 100. But old age has not and will never plague them. In the minds of those who knew them, and for we others, who only imagine them, they will be forever young.

The deaths of Ruby Colvin and Homer Walters seem cruel and senseless---so easily avoided—inflicting so much pain on their families. But Ruby and Homer’s lost lives surely saved many others down the stretch of time since that fateful evening three quarters of a century ago. To my knowledge, no other person has lost their life at that place since. Ruby and Homer’s tragic experience has been told and re-told to three generations now: “Beware the deep waters of the Rock Quarry. They have claimed others. They will claim you.”

God bless Ruby Colvin and Homer Walters! Let us never forget them!

The Newspaper Account

The drowning deaths of Ruby Colvin and Homer Walters were reported in the Eldon Advertiser the week following the tragedy and that account, transcribed from microfilm, is inserted below. Aside from a couple of obvious typographical mistakes that have been corrected, it appears to be thorough and accurately relates the account of the only known eyewitness, 19 year old Gerald Haynes.

Eldon Advertiser

Thursday, July 22, 1937

No. 22, Volume 55

2,050 copies printed.

Couple Drowned in Abandoned Quarry West of Eugene

Ruby Colvin, 21, and Homer Walters, 25, were victims of tragedy Friday night at 9:00 o'clock.

The 1937 vacation season death toll by drowning was increased by two Friday night when Ruby Colvin and Homer Walters of the Etterville community waded in beyond their depth in the old lime kiln rock quarry at Gartside on the Rock Island railroad midway between Eugene and Etterville.

About nine o'clock that night they, accompanied by Gerald Haynes, of the same community, went to the quarry, which had filled with water to a depth of 25 or 30 feet in places, to go in swimming. For a number of years the pool, which is about 200 feet long and almost that wide, had been used for swimming by people of that neighborhood. In places the pool had an abrupt decline. When the trio parked the car at the east end of the quarry, Miss Colvin and Walters went to the northwest corner of the pond and entered the water, young Haynes declining to go in as he declared he could not swim. When he heard calls for help he went to their aid and waded out till the water struck him under the arm pits, but he could not quite reach them. Walters could swim, but the Colvin girl could not, and it is presumed that she clung to him when she realized that she was drowning.

When Haynes saw them disappear, he got into the car, which belonged to Walters, and drove down to the service station at the junction of highways 54 and 17, two miles north of Eugene. From there he phoned to people in Eugene and to Sheriff Tyler. A rescue party, including F.V. Kallenbach and Truman Vernon was organized at Eugene and a small boat belonging to Jesse Logrbrinck, which was stored in town, was taken to the pool. They and Sheriff Tyler and Deputy Asa Gunn recovered the two bodies about 3:00 o'clock the morning following the drowning by the use of lines and fish hooks.

The Phillips Funeral Home of Eldon and the County Coroner, Dr. G.D. Walker, were notified. Dr. Walker decided that the drowning was accidental. The bodies were taken to the Phillips mortuary and prepared for burial. An undertaker, accompanied by the parents of Walters, came from Poplar Bluff and the body of young Walters was taken to Van Buren for burial. Walters, who was 25 years old, had been making his home with Mr. and Mrs. Lyman Gartin, near Etterville, for the past eight years. He was the son of Mr. and Mrs. George Walters of Fremont, MO. His funeral was held Monday.

Miss Colvin was the daughter of Mr. and Mrs. Pete Colvin. Mrs. Colvin being a daughter of Mr. and Mrs. George Wyrick (both now deceased) who lived near Tuscumbia. The Colvin family lives on the Chester Farris farm, a few miles south of Etterville. Miss Colvin is survived by the parents and the following brothers and sisters, all at home: Bertha, Evelyn, Bonnie, George and Arthur. Funeral services were held for her at Mt. Zion, Sunday afternoon, conducted by Rev. Omar Hickey of Eugene, and burial was in the church cemetery nearby, with Phillips Funeral Home in charge of burial arrangements.

In 2012, Ruby Colvin has two surviving sisters, Bertha (Colvin) Campbell, who lives with her daughter, Sandra Dillard, in Grapeland, TX; and Bonnie (Colvin) Rhoades, who lives in Olathe, KS. Bonnie provided a copy of an enlarged and re-touched photograph of her older sister, Ruby.

Don Washburn, nephew of Homer Walters, lives in Fremont, MO and was kind enough to find an old family snapshot and crop Homer’s picture and send to me, along with a photo of Homer’s grave.

This story brought back sad memories to both families---some long forgotten. I wish to thank Bertha, Sandra, Bonnie and Don for their cooperation and continuing interest. I know this has not been easy.

Although the newspaper account jibes with much of what I have heard over the years, there remain many questions about what happened that fateful evening in 1937.

Bertha described Ruby as a kind person who was pretty much a homebody. The younger girls, including Bertha, chopped wood and did outside chores, whereas Ruby confined her work to the indoors, including doing the cooking, washing and caring for the family. The girl’s mother, Margerie (Wyrick) Colvin, suffered from chronic ill health and was sometimes bedridden for days. Ruby seems to have assumed the role of a “stand in” mom for her younger siblings. She was said to be a delicate girl, “afraid of snakes, bugs, and stickers” and “would have just been in the way” doing outside farm work. According to Bertha, Ruby “was involved with a local church and rarely went anywhere outside the home.” Given the circumstances of Ruby’s death, Sandra Dillard found the latter statement by her mother “very interesting.”

My parents always referred to a “group” or a “bunch” of young people reported to be at the quarry the evening of the drownings. I was surprised, as were Bonnie’s sisters, that Gerald Haynes reported that only Homer, Bonnie and he were present at the quarry when the tragedy occurred. Sandra Dillard quotes her mother, Bertha, as saying: “There had to have been more young people involved. He (Ruby and Bertha’s father, Pete Colvin) was very strict on all of us and extremely protective of his oldest daughter.” Bertha does not remember where the group said they were going, but, “It definitely was not swimming.”

Bertha and Bonnie agree that their father was well aware that Ruby could not swim and would never have permitted her to go along if he had known her eventual destination.

“Nor would Pete Colvin have let Ruby go off alone with two young men,” Sandra Dillard added.

Neither Bertha nor Bonnie believe that Ruby had a romantic relationship with Homer Walters, Gerald Haynes, or anyone else at the time of her death.

It seems there was at least one additional person in the group that left the Colvin house in Homer Walter’s car that evening. Bertha, now well into her 90’s, distinctly remembers fifteen year old Evelyn Helsel coming to the Colvin house that day. Evelyn, who was not a favorite of Bertha’s, begged and insisted that Ruby go along with the group. Why was Evelyn so determined that Ruby go along? Maybe she was under strict orders that if the older Ruby didn’t go, she would not be able to go either.

Even though Ruby Colvin was twenty one, well past the age of majority for women, she lived under Peter and Margerie’s roof and they had the final say. All parents have heard the, “Oh dad, I never get to go any place,” wheedle; as well as the good faith promise, “mom, I’ll be home by 9:00.” Pete Colvin loved his daughters and wanted them to be happy and have good times. Whatever were the assurances given and the promises made, Peter Colvin reluctantly told Ruby she could go. He would regret it for the rest of his life.

What about young John Lyman Gartin? Where was the 15 year old son of Lyman and Betty (Deffenbaugh) Gartin that Friday evening? Homer Walters resided with the Gartins and had worked on the Gartin’s farm for eight years. What had brought Mr. Walters to Miller County from his roots in the beautiful float stream country of southern Missouri? No one seems to know, but by living so long together, John and Homer likely thought of themselves as brothers. In September of 1939, at the tender ages of eighteen, John W. Gartin and Evelyn S. Helsel got married. This was only two years after the drownings. If Evelyn Helsel was riding around in Homer’s car, it’s a pretty good bet John L. Gartin was along. By filling out the foursome, Ruby Colvin could have been considered Homer Walter’s “date” for the evening. Nineteen year old Gerald Haynes was either along or joined the group later.

By auto, the direct path to the old Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company quarry would take the group east from Etterville about two miles on the newly built U.S. 54, where they would have made a right turn on the old Spring Garden to Tuscumbia road, now called “Abbott Road.” Then, as noted in Part II, in less than a mile, they would have made a right turn and traveled through the Jenkins farm one half mile or so, crossed over the Rock Island line using the bridge at “Gartside”, and then driven on a narrow, hard chat road up the hill to the quarry’s southeast entry.

Did the group that included Homer Walters, Ruby Colvin, and Evelyn Helsel go directly to the quarry? Somehow, I doubt it. It was likely late afternoon when they left the Colvins, but in July it wasn’t even close to being dark. The strict Pete Colvin may have even ordered Ruby to “be home by dark.” According to the U.S. Naval Observatory, sunset came to nearby Jefferson City at 7:32 Central Standard Time that July 16. The incident happened at around 9:00 PM., some 1 1/2 hours after the sun had set behind a high bluff overlooking the quarry’s waters. How did the group spend its time from broad daylight, well before sunset, until almost full darkness at 9:00 P.M.?

After 75 years, no one knows the answer, but let me offer the following account. Though admittedly speculative and fictional, it seems plausible:

As the group in Homer Colvin’s car headed east toward Eugene, an inviting temptation presented itself. Only ½ mile past the turn-off that would have taken them to the rock quarry sat a well-known tavern, dance hall and honky-tonk run by Les and Lola Prince. Fascinatingly, Les & Lola called their business a “service station” in the 1940 Census. Well, they did sell gas. Located at the junction of State Highway 17 and U.S. 54, it was a thriving enterprise and on a Friday evening would soon be “jumping.” Local church-going Protestants generally avoided the place, but for a more fun loving class of people, it was heavily patronized. Sale of beer and wine to minors and crap shooting dice games were mostly overlooked by authorities. Les and Lola’s popular “Junction Place”, was notorious for late-night boisterous conduct and parking lot fights.

Ruby Colvin, a retiring, church going, homebody who didn’t get out of the house much, would have been an odd fit at Les & Lola’s. Peer pressure and a desire to not be a “stick in the mud” may have kept her there and the conversation pleasant. Maybe she consumed a Coca Cola or 7-Up treated by Homer. Some barfly, already deep in his cups, kept playing Tommy Dorsey’s “Marie” and “I’m Getting Sentimental Over You” on the juke box. They were Ruby’s favorite songs. With the doors open, the bass notes could be heard all the way to Eugene----maybe even to the rock quarry itself. Homer and Ruby took an awkward but earnest turn or two around the dance floor---all seemed well. It was still early, hours before raucous laughter and angry shouts would drown out the Dorsey Brothers. But as time waned, Pete Colvin’s stern decree to “be home before dark” spoke to Ruby and she told Homer she had to go home. The others were having a great time---she felt guilty bringing up the subject. Homer said, “Look, I’ll run Ruby home and come back to get you all.” Ruby, a little uncomfortable being alone in just a twosome with Homer, invited Gerald Haynes, whom she knew well, to ride along. In a spirit of chivalry, he agreed. Homer winced.

The threesome left the tavern and headed west toward Etterville in Homer’s V-8 powered ’34 Ford “John Dillinger Special.” The stars were not yet out and the western sky was still bright above the horizon. Anxious to extend the evening with Ruby, Homer proposed a quick trip to the “kiln” for a little swim. “Man, it’s still hot out here---a cool dip is just what we need.” Ruby had never been to the rock quarry, had no swim suit, didn’t know how to swim, and didn’t dare arrive home soaking wet. Another half hour’s absence might bring down her father’s wrath. But Homer was determined and it was his car, after all. Gerald Haynes, another non-swimmer, was unenthusiastic but didn’t put up a fuss.

Within minutes, needing the car’s headlights to penetrate the gloom, they arrived at the water’s edge. Taking Ruby’s hand, Homer said, “Let’s walk around to the other side—it’s the best place to swim.”

Taking his cue, Gerald said, “You two go ahead, I’ll just stick around here.“

Finally confessing, Ruby said, “Homer I can’t get in---I don’t know how deep it is and I can’t swim.” The dim light revealed boulders strewn about---good places for snakes –Ruby was terrified of snakes and other creeping, crawling, buzzing, creatures. She was in a state of half fear and half uncertainty.

“It’s O.K., I’ll go in---you can just wade a little on the edges,” he said reassuringly. In the near darkness, Homer disappeared and returned stripped to his skivvies. Stepping from stone to stone, he moved for a few yards along a partially submerged boulder pile and then dived in. The water was bracingly cold as he surfaced, breast stroked nearly to the middle of the pool, and then flipped on his back and stroked back toward where Ruby was sitting quietly with her ankles dangling in the water. “The water's great, you ought’a come in---I won’t let you drown”---he said jestingly.

“I can’t---I’m scared of the water,” Ruby replied as she arose and turned to climb up the steep, hard -packed gravel bank. Then disaster struck---her wet feet caused her to slip and slide partially into the water---she clutched some nearby cattails, but unrooted, they lifted away in her hand. Ruby then slipped backward into 30 feet of water. Going under with a large splash, she soon surfaced, choking and flailing awkwardly amid a fountain of bubbles.

Homer was there within moments, the skirt of Ruby’s light print dress created a visible circle, marking her location. He at first welcomed her tight double armed embrace, but then he realized she had one of his arms pinned tightly to his body and a scissor hold on the opposite leg. He knew they were in trouble. Homer managed, with his free stroking hand and single leg kick, to push their combined weights to the surface twice. Each time, Ruby, panicked and fighting for her life, literally climbed up on his shoulders, pushing him back under and immersing them both. With his last remaining air, Homer yelled to Gerald for help.

The rest of the story was told by Gerald Haynes to the authorities later that evening when they were summoned to retrieve the bodies. Gerald said he waded out as far as he could, probably along the same little jetty of rocks where Homer had first entered the water, but could not reach them. A sterile place, the abandoned quarry was barren of fallen tree limbs, ropes or any objects to assist those in peril. Helpless, he saw the couple slip beneath the water for the last time. Finally, the bubbling stopped and the enormity of what he had witnessed bent him nearly double with nausea. “Oh, my God---this can’t be,” he exclaimed. His friends, there only seconds before, were gone down and would not be coming up. Gerald ran for Homer’s car and drove quickly away.

A strange quiet settled over the quarry for a few minutes. Then the crickets and katydids resumed their comforting melodious tones of summer. A lone bullfrog, climbed onto a rock on the other side and began summoning a mate.

Life moved on.

Epilogue

Gerald Haynes might have been expected to stop at the first inhabited place to sound an alarm and summon authorities. Driving to the “service station” at the junction, he passed several houses whose families had “party line” telephones hooked into the Eugene “central” telephone operator. Why was he so intent on going to the junction? Could it be that in a state of fear and shock, his only thought was to return from where he had come? To tell John, Evelyn, and others what had happened and to decide what to do?

The deaths of Homer and Ruby left their families devastated and inconsolable. Peter Colvin placed the blame on himself for Ruby’s death and took to heavy drinking. Already in puny health, his wife, Margerie, took to her bed---for all intents and purposes an invalid for the rest of her life. Ruby’s niece, Sandra Ballard, a community college teacher in Texas said, “The family simply disintegrated.” The remaining girls married very young. Two married much older men. The boys joined the Army as soon as they were old enough. Eventually, Peter and Margerie separated, although there is evidence that they might have reconciled and been living together at the time of Margerie’s death in 1951.

The lives of John W. Gartin and Evelyn S. Helsel, who almost certainly accompanied Ruby Colvin and Homer Walters that fateful evening, would be bound forever with those of Lola Mae Prince and her brother, Henry Francis Whitener. Henry lived with the Princes and helped them run the tavern at the junction of 17 and 54. As noted earlier, John Gartin and Evelyn Helsel were married in 1939. Sometime before 1949, they were divorced.

In 1947, Lola Prince’s husband, Les Prince, drowned while fishing at night with friends James “Poodle” Gray, Brice Spalding, and Clyde Hawken. Their boat capsized in the flooded Osage River just below Tuscumbia. Spalding and Hawken managed to swim out. Les Prince could not swim. Poodle Gray heard his panicked screams and turned back to help. With Prince clinging desperately to Gray, they drowned together—much in the manner of Homer Walters and Ruby Colvin.

In 1949, the unattached John W. Gartin married the widowed Lola Mae Prince. In the very same year, John W. Gartin’s ex-wife, Evelyn Helsel Gartin, married Lola’s brother, Henry Francis Whitener. Thus Evelyn became John’s sister-in-law by marriage and John became Evelyn’s brother-in-law by marriage. These unusual relationships must have made for some lively family dinners.

In closing, I urge the reader to consider:

If Homer Walters and Ruby Colvin were at Les & Lola Prince’s tavern sometime in the evening of July 16, 1937, and if Poodle Gray happened to stop in…. think of the star crossed fates of those four coming together at the same time and place: Homer, Poodle, Les, and Ruby. Two of the merry makers would die that very evening. The Reaper would patiently wait ten years for the other two. The stories would be the same.

Psalms 147:4 says of the Almighty:

He telleth the number of stars;

He calleth them all by name.

Surely the stars for Homer and Ruby, as well as Les and Poodle, already had their names on the days they were born.

I am certainly very grateful to Alan Wright for submitting this intriguing, historical but also sad story about the deaths of two young Miller County residents, Ruby Colvin and Homer Walters. In addition, I have learned much I didn’t know about this area of our county, especially the history of the old quarry and the Spring Garden Marble & White Lime Company. I am sure our readers will have the same opinion as well.

Alan has other publications including his book, “Murder on Rouse Hill” which was featured in a previous Progress Notes.

Alan also has a page of historical photographs on our website which you can find under the heading “Yesterdays” on our home page.

Thanks Alan!

That’s all for this week.

Joe Pryor

Previous article links are in a dropdown menu at the top of all of the pages.

|