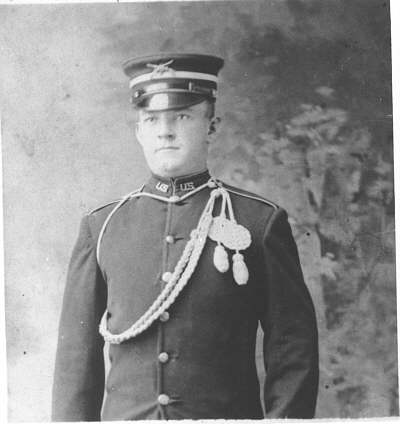

Letters Home #10John Edwards Letters John Gill Edwards at age 19.

Have had the Dingue fever for the past few days. It certainly did make me feel bad. I have only got 25 days to discharge. God only knows when I will get home, about Nov 25 I think. I don’t care much if I never get there or not. Sunday and I have worked all day. Such work as it is.

Chow is rotten. It looks impossible (?) for a man to live on such chow. Have no tables to eat off of. Just sit down in the waste and filth. I live down in the hold of the ship sleep on a little iron clad berth (?) about 2 x 6 – isn’t so bad. But chow oh ye Gods. But I suppose I have no pick concerning military necessity has no mercy so they say.

Went down to US army transport Dix this morning to watch 2 – 14 inch guns unloaded. Ye gods, what a monster weapons they use on man at this date of civilization.

Been on duty all day. The gen came over to inspect qurs. I wish he woundn’t come any more. His voice is more like a lion than a human being. Speeks to soldiers like a man driving slaves. LETTERS TO EDITOR OF THE MILLER COUNTY AUTOGRAM SENTINEL

Dear Editor: While sitting in y canvas divan this morning doing nothing in particular but letting my mind drift over bygone days, I just happened to think of my old home and wonder if some of my friends and relatives would like to hear a few words pertaining to conditions on the Mexican border. Now, to begin with, things are not going so bad with us along the border as is supposed. It's true that there is quite a bit of homesickness among the men in the 2nd Mo. Infantry but as time drifts along, home times become more broken and we get accustomed to our duties and homesickness, I think, will soon be a thing of the past. Things are very quiet on the border now; about the only danger we encounter is from centipeds and tarantulas. Our hardships are just about the same as any regular organization would encounter in the field. It's true that there are many privations as we are 45 miles from the nearest railroad station which is Loredo, Texas; supplies have to be sent out by truck trains and they are delayed a great many times. Consequently we are deprived of many things that we would like to have such as bread and ice. And when we don't get those, we have to drink warm water and eat hardtack. Hardtack and hot water, in my estimation, is a rather poor diet. We have good tents and cots to sleep on, and the officers do everything in their power to make life as cheerful for us as possible. There is undress guard and fatigue parties to perform, but as the old saying goes "Military necessity has mercy on no one." There is a rumor out that we will be sent home soon, but we can't tell. The 1st and 3rd Mo. regiments were sent back to the mobilization camp at Nevada about a month ago but when we come is left entirely up to the War Department. Personally, I hope it will be soon. This isn't a bag organization for militia. There is a great deal for us to learn yet. We have learned considerable and are eager to learn more. Altogether we are quite a happy family. I think I've said about all I can for this time. Wishing everyone around home the best the season can bring.

P.S. Clarence Bear who is a sergeant in this company is worthy of mention I think. If you see fit to print this, do so; if you don't, throw it into the waste basket and another masterpiece will have been born to blush unseen and waste its sweetness in the desert air. J.E.

Editors Autogram: It has been some time since your readers heard from me, so it being after supper time and the day's work is done, I will take pleasure in informing the Miller county public that the famous "Houn' Dawg" regiment is homeward bound. Where the 2nd Missouri Infantry got its name as the Famous Houn' Dawg regiment remains a mystery to me, but nevertheless she is known form New York to Mexico City, and even if we are too proud to fight and didn't get to go across the Rio Grande, she will always be remembered by those who have come in contact with her wherever she has gone, The Houn' Dawg regiment is one of the crack regiments that the border has ever seen and is far ahead of many of the regular organizations; any Missourian that knows anything about her, is proud of her or he isn't an American, that's all. Some are proud to get home but the majority of us feel that we have not accomplished the mission that we sought to accomplish and we are loth to return home knowing in our own hearts that six long months of our lives have been wasted, sweltering in the border camps, undergoing hardships and privations and all other things that help make a soldier's life hard, without accomplishing anything. No doubt it has been a great deal of experience for some of us, and lots of training for us, but the majority of us have had experience and training and training in the army, and we went there for the express purpose of fighting, and down deep in our hearts we are not satisfied with coming away without a scrap. We left our homes in time of need; left good jobs with better pay to answer our country's call, we thought, in time of need. But, alas, after six months of drilling, hiking and guarding, we are ordered home. Too proud to fight? I guess that's the right word for it. Oh, it's a down hearted bunch all right, returning home without a single notch on their guns. Well,, we left Laredo, Texas, last Thursday, the 28th; arrived here Saturday the 31st. I suppose we will be mustered out by the 10th. Sergeant Bear and I are the only ones in this regiment having parents that are readers of your paper so I suppose they will receive the glad tidings with cheerful hearts that their prodigal sons are homeward bound. I think I've written all I can for this time. Hoping all of my friends and relatives around the old home town have had a merry Christmas and a happy New Year, I remain the original boy in arms, Corporal John Edwards

Editor Autogram: Just a few words about the draft soldiers. There isn't any doubt in my mind but that there is just as good fighting material in the draft army as there is in the volunteer army, but there isn't the right spirit among them. They have been drafted into the army against their will, and that's why they haven't the spirit of the volunteers. The volunteer soldier scorns the conscript man and his road is going to be rocky for a time at least, until the feeling has died away. My personal opinion about it is this (and I don't care a continental what people think about it either, for I'm a Yankee soldier and accustomed to speaking my opinion): I'd rather go to jail any time than to be drafted in the army. I think that if a country isn't worth fighting for it isn't worth living in. Some will say, "Oh well, there are plenty without me." That isn't the question, and I want to say right here, that no true American will say anything of the kind if he cares anything about the welfare of dear old U.S.A., and above all, old Glory. I've served five years in the army. Suppose I'd say, "O well, I've served my time, let some one else go." Would I say anything of the kind? Never; I'd die a thousand deaths on the battlefield for my country before I'd say anything of the kind. Some will say, "I've got a mother and father and I'm needed at home." Suppose you have; I have a father, mother, brothers and sisters, and a sweetheart ( which every soldier has) and I love them all as well almost as I love my Savior, and I'm needed at home too, but my country needs me more. That's why I'm here. If we permit the iron hand of German autocracy to enslave us, disgrace Old Glory, over run dear U.S.A., a country above all countries, what good is all those interests back home going to do us? I can answer that question; none whatever, of course we have to have men on the farms, but there's plenty of married men to run the farms. Take our own home town, Tuscumbia, for instance. I know some married men there that would be better off if they were in the army. They aren't any good to their families; they don't work over two days out of a week. They could get $30 per month in the army; they could supply their families with more out of that than they give them when they are there. Still there are some big, husky unmarried men round Tuscumbia who aren't any good to themselves or the community either, who would make excellent soldiers, if their backs weren't the color of their socks (yellow). They haven't any manhood about them at all. When our country called I didn't wait for the draft; I stepped forward like a man and volunteered like a man. I've been a soldier for five years and I've never seen a day in those years that I wasn't proud for what my uniform stood for. In a few brief weeks my regiment will sail for France. I'm not going to whimper; I'm going forward like a man. That's what I volunteered for. Come on, boys, if you have any manhood, now's the time to show it. I've heard the girls and women say so many times, "We are only women; what can we do?" I'll tell you what you can do. You can organize clubs, and every pair of gloves you knit will help warm some soldiers hands on the field of battle; a pair of socks, or a bandage to bind up the wounds of some bleeding soldier on the battlefield will help. Make some jelly and turn it in to the Red Cross. Some hungry soldier will get it and say a prayer for you. All of these little comforts are appreciated and help wonderfully. They help the morale of the army and make the soldier feel that he has something back home to fight for. Girls, you can all help and I implore you to do it. I've tried to speak frankly in this letter and straight from the shoulder. I've tried to make it as interesting as possible, and if I have said anything that has hurt anyone's feelings it can't be helped, for the truth is always what hurts. I've said enough for this time. Hoping all of my friends and relatives will be glad to hear of my whereabouts, I am

Camp Logan, Houston, Tex., Oct. 23, 1917Editor of the Autogram, Tuscumbia, Mo.: I have been at places in days gone by that I thought I would like better than Missouri, but as the old saying goes, "where one is born and reared will always be home, sweet home to him." Dear reader, in my experience I have always found this to be the fact, and when the time came for discharge or muster out, or whatever the case may have been, I've always found myself turning my footsteps toward the hills of old Missouri. I'd about made up my mind that I had written my share of letters to the dear old paper , which every soldier from Miller county welcomes as a letter from home, but owing to the fact that the old 5th regiment has been split up and converted into machine gun battalions, and became a part of the regular U.S. army, I write this for the purpose of giving you my correct address more than anything else. Things are rolling along in a war-like manner here at this camp. The most interesting thing in the last week is the sale of Liberty bonds. The soldiers of this camp have bought more than two millions. The Government made it plain to us that we had made enough sacrifice when we offered our lives to our country, but that it was merely an inducement that was offered the soldiers to save their money. I have just read the Autogram. I have scanned its pages thoroughly. I notice a letter from the boys at Camp Funston, thanking the ladies of Miller county for the rousing send off and the many comforts they had bestowed upon them. I have just a few words to say about this. I notice in this paper as in all other papers, about the rousing send offs, and the big banquets tendered the drafted men. Where does the Volunteer Soldier come in? Was I or any other Volunteer from Miller county given a banquet or escourted to the train by a band? Did the entire population turn out to pat me or the rest of the volunteers on the back and bid us God speed? Absolutely, no. We do not wish to make it appear that we are heroes just because we are volunteers, but we do wish to have our share of the praise. I think we have it coming. The selected men may be all right, but why do they call them selected men? I would term them picked men -picked because they were plucked. I do not wish to hurt anyone's feelings in this letter. All I ask for is to be recognized as a volunteer composing a unit of Uncle Sam's great army.

Why didn't I wait to be drafted;

And be led to the train by a band; Or put in a claim for exemption,. Oh, why did I hold up my hand? Why didn't I wait to be cheered? For the drafted men get all the credit While I merely volunteered; And nobody gave me a banquet,. Nobody said a kind word,' The puffs of the engine and the grind of the wheels,' Was the good-bye I heard, And off to the training camp hustled, To be trained for the next half year, And in the shuffle forgotten, I was only a volunteer, And perhaps some day when my little boy sits on my knee And asks what I did in the Great war, And his little eyes look up at me, I will have to look into those eyes That at me so trustingly peer, And tell him I wasn't drafted, 1 was only a volunteer.

As I have nothing to do this afternoon but write, I'll try once more to express a few of my thoughts that have been in my mind for some time. The American people have at last come to the realization, I think, that we are at war. But it seems that there is still room for improvement. Those of you that haven't any sons in the army, I'm afraid, don't quite realize and appreciate that we of America are at war. You will ask yourself at the beginning of this letter, I suppose, why should a soldier write such a letter? Gentle reader, let me explain. I do not write this letter in my own behalf, because I have been in the army long enough to take my share of what comes and go along with it without any grumbling. What I want every citizen of Miller county to do is to wake up to the realization that we are at war. It's quite true that you have done much from a financial standpoint and I assure you that we appreciate it. But you have only begun to give. It is easy to give a dollar to the Red Cross or to buy a Liberty Bond, but wait until you have to give your sons. Then you can realize that America is at war, even if it is thousands of miles from the shores of peaceful America, you are tasting its dregs and it is brought to your very door. The son who is called to the colors leaves his home with the flush of unknown adventure on his cheeks. Let not the parents be deceived. Tomorrow the light of hope may fade from his eyes and his smile be replaced by a gaunt look of suffering. When this crisis comes he needs more than bandages, medicines, food and warmth. He needs some concrete indication that those at home are with him in spirit and behind him in his hour of suffering. But this is war. It is as glorious to die in camp as on the field of battle. In the greater conception of service, the fact that you must regard coldly and dispassionately is that our boys are experiencing the fortunes of war, real war with the glamour and romance dissipated by hardships. If all the mothers whose sons have marched away could be with them in the flesh in their hour of peril, with them in the hospitals, ministering to their creative needs, or with them in their moments of triumph when they have bravely fought and won, then there would be no need for a plea in behalf of these boys. But war dictates that this cannot be the case. Miles upon miles divide blood relations and prevent mother from being with her son in more than spirit. What an inspiring thought it is to think of every soldier of the U.S.A. going into battle with a mother's hand resting on his shoulder, until he shall be at death's grip with the enemy? While this is an impossibility, you can conceive a less romantic method for serving those at the front, and we sincerely hope that you will do all in your power, yes, even to the utmost, to back your boy and some one else's boy as they go over the top to fight our fight. A letter, a few simple lines often written will convey a message of hope when it is most needed. A few small gifts, designed to warm his body and the heart of the recipient, are like a mother's kiss to those who need them. The young soldiers who are being called to the colors every day, are the ones that need those things, because they aren't used to being away from home. It will be hard for them to become accustomed to the stern military discipline that a young soldier is subjected to in order to fit him to beat the Hun. I am trying as near as I can to picture the role of an American soldier as I understand it. But mothers and fathers seated around about the evening lamp, in the shelter of your home, where there is today a vacant chair, do not forget that your son has perhaps a comrade in arms, another brave American lad. Indications that he is fighting are given by the casualty list which briefly tells that a boy in khaki has died for his country .The report indicates that the person to be notified of his death is a nearest friend. He appears to have had no relatives, no one save a friend in all this great land who was interested in his welfare. What does this mean? Probably that this boy had no parents at home to stand behind him and to send him words of encouragement, leaving him dependent upon his fellow soldiers and those brave women who are nursing our wounded. Here, again lies a great opportunity to do a parent's duty to a son; not only your own but also a son of the American people who has only a "nearest friend." But what of the mother? Can we go so far as to look into the mind of the mother who has given her cherished son to the cause? What do we see? Perhaps a mental picture of her boy in the trenches. From what she has read and from what she has heard she must no doubt conceive a vivid picture, terrible in detail. This she sees and tries to dissipate the vision. She cannot realize that her boy, the little fellow she once nursed and fondled, would ever have to face such horror. But such is the case and terrible though it is, mothers everywhere must brand this conception as true and must look at it in the light of a grim reality. So as a soldier with long service who knows how to take the situation in his own hands and cope with it, I ask you as one who knows the majority of the game at least, to stand behind those young boys who are going forward to join the colors. If you at home could see the situation from the angle that we can, no difference how remote a spot you live from actual realities, I'm sure you could all do more. It is true you are asked to give more and more every day until you wonder when it all will cease. But here again, think for a moment, and you'll find that we are at war, and remember what you are giving you' II get back some day. You know very well what the soldier is giving. The story is old and has been told many times. I have tried to picture things in this letter in a way that you can understand them. I leave the rest to you. Best regards to friends and relatives.

The following is a copy of a letter received by Mr. and Mrs. John Bilyeu of Hancock from their son-in-law John Edwards of near Tuscumbia who is now at Fairbanks, Alaska. Mr. and Mrs. Bilyeu ask that the letter be printed in the Autogram.

I promised you I would wrige to you and it's about time I was getting at it. I arrived here last Monday and have worked every day until today. But they say when the weather gets warmer there won't be any Sundays. We had a nice trip up here, but I got pretty tired of it before it ended. We left Kansas City at 11:30 the 10th. Saw all the folks. Got to Des Moines the 11th, to St. Paul next day, thence to Winnipeg, Canada, then on to Edmonton. There we took a plane. I'd never been up since the other war but I want you to know it was the most thrilling thing imagineable. It was pretty stormy and we went up to 4,000 feet above the clouds and below us was a solid floor of white fleecy filmy clouds or fog in a million different shapes and forms with the sun shining brilliant, so brilliant it is beyond my poor pen to describe. We were just up there floating along in the heavens. It seemed that my heavenly father was very near to me and you all seemed near to me, so near in fact that I could feel your very presence. Then we were at White Horse. We stayed over Sunday and started for Fairbanks at 5 a.m. Got there at 8 a.m. When I got off the plane it was 4 below zero. I thought I'd freeze the cold was so intense it gripped me like a vise. I have had one letter from Minnie. She reports the river flooded as usual so from a financial standpoint I guess it's better I'm here. It's pretty bad to be absent from my loved ones and I don't aim for it to happen too often. I am well, not too happy. Work is very easy so far. They sure feed me good. Living conditions and bed are pretty common. Nothing like my little mamma's big white feather bed. I've slept cold every nite since I've been here. There is a big range of beautiful snow-capped mountains in y front yard, but they say they are from 40 to 80 miles away. But it seems that one can almost reach out and touch them. When you see Otto Ponder, Lewis is here with me and is doing all right. Clyde is here and sends regards to you. Hope you get to go down and see Minnie and the children. Tell Freemans hello for me. I think I can take it if you all write pretty often. This writing is going to run into money at 8 cents a letter. I must close now. Deep love and respects to you and may the God of battles ever attend you.

John Gill Edwards at age 19. |

|

P.O. Box 57 Tuscumbia, MO 65082 http://www.MillerCountyMuseum.org © 2007 - Miller County Historical Society |

|